'A reader who buys or reads a book to associate themselves with it definitely needs a therapeutic intervention': Julian Evans on prose style

Our new questions answered by the author of Undefeatable

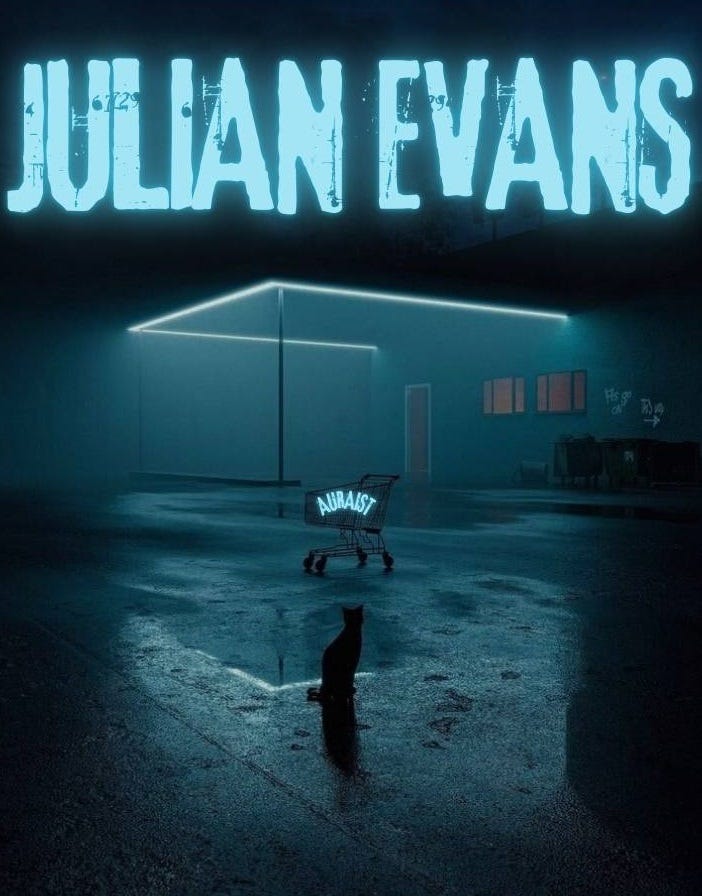

Welcome to the 1500 new subscribers who’ve signed up in the past month, thanks to the readers recommending and otherwise promoting Auraist.

Gift a friend a subscription to the only publication set up solely to champion beautiful writing:

COMING SOON:

—The best-written books of the year and century to date, by the best writers and literary Substackers.

—Nina Schuyler answers our new questions on style.

IN TODAY’S ISSUE

—‘The darkness has no planes or dimensions, I can’t tell if it’s going up or down or side to side or how far, it is without form, and void; and darkness is on the face of the Black Sea, and on the city and the Starosinna bus station’: the opening pages of Julian Evans’s memoir Undefeatable.

—’my writing life has been dedicated to showing that windiness the door’: Evans’s discussion of prose style.

If you’d like us to consider your own recent release or a work you’ve serialised on Substack, sign up for a paid subscription via the button below and email a copy of your book to auraist@substack.com. If we pick your submission we’ll invite you to write an article on prose style that will be included in the published collection of these pieces by many of the world’s best writers.

Available on request at the same email address: the fully illustrated epub of The Demon Inside David Lynch.

A paid subscription also gives readers access to our full archive of dozens of author masterclasses on prose style, hundreds of picks from recent releases and prize shortlists, the best-written books of the century, and extracts from many of these. Or you can join the 32K discerning readers who’ve followed us or subscribed for free access to posts for a fortnight after publication.

You can also join the Substacks recommending Auraist and receive a complimentary paid subscription.

BLACK AND WHITE

The darkness has no planes or dimensions, I can’t tell if it’s going up or down or side to side or how far, it is without form, and void; and darkness is on the face of the Black Sea, and on the city and the Starosinna bus station. It has been like this since the sun set two hours ago, and with the darkness has come no mobile signal. Oleksandr, who was on the bus with me from Chișinău, is on a different network, with just enough signal to call a taxi. Walking blindly left, right, left again, after five minutes we find where the taxi’s parked. Oleksandr and I wish each other luck and goodbye.

I have arranged to meet my former brother-in-law at his beach house south of the city. He has firewood. It’s freezing, so firewood is important. Driving out of the city is like moving through a dark room full of remote-controlled toy cars trying not to crash into each other. Sometimes they don’t succeed: they shunt each other, and ram each other at intersections because the traffic lights are out, or they turn left and ram each other that way. But Dima, my driver, is from Odesa and drives well. I try to call my ex-brother-in-law. No signal. It’s now raining hard.

We reach the beach village of Chernomorka and turn left onto the narrow main street of the enclave of beach houses. Dima’s headlights are the only lights.

The beach house has vanished in the dark. I know where it is, on a lane that runs off the main street. Dima drives up and down. I get out and walk in the rain down a few of the black lanes, but the beach house isn’t there. We go back to the gate at the entrance, but the watchman doesn’t know which is Vadym’s house.

‘Let’s try again,’ Dima says.

This time I walk methodically down each lane, as the freezing rain laughs down the back of my neck. Finally I make out a familiar sheet-iron gate and first-floor balcony. I thump the gate and shout Vadym’s name, but the house is as dark as the night and the only sign anyone lives there is an uncovered soaking heap of firewood in the front yard.

Dima drives carefully back to the city, to one of two hotels that I remember. I stayed a few nights at the Chornoye Morye more than twenty years ago and it’s still there at the intersection of Rishelievska Street and Mala Arnautska Street, a broad stubby version of the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

I have to prise the sliding glass doors apart with my fingertips. Inside is complete darkness. I cannot see a reception desk. Two security guys whose faces I also cannot see materialise in front of me. I ask if I can have a room. Dima has followed me in and turns his phone torch on and explains the situation. The taller security guy’s badge on his hoodie says ‘Ilya’.

‘We have no electricity, heating or water.’

‘Outstanding,’ I say.

‘We will take you to the third floor. We will shut the door. You cannot leave till the morning because we only have the security pass key. If you leave the room, you won’t be able to go back in.’

‘Thank you.’

I give Ilya a 50-euro deposit. I pay Dima double what he asks me, because his refusal to abandon me has saved me. Ilya’s shorter colleague, unshaven and grinning so he looks a little like a jailer in a fairytale, leads the way outside and round to the back of the hotel, up three flights of fire-escape stairs to a freezing corridor and room number 324, looking out on the darkness of Mala Arnautska. Still grinning, he wishes me ‘Goodnight’ and shuts the door behind him.

From the window of my room, Mala Arnautska is not completely dark. The only electric light for a block in both directions streams, like a star in the east, from a cherry-neon outline across the street of a naked woman on tiptoe, and above her the words ‘Strip Bar’.

Sitting on one of the beds in the not-quite dark, I wonder why I let myself get into this situation. Falling back and staring at the ceiling, I tell myself I knew what a blackout would be like. On the way from Chişinǎu airport to the Moldovan border at Palanca, the last leg of a journey that started at London Luton airport at 4.30 this morning, I was scrolling through my phone for news of Russia’s latest missile and drone attacks as they struck Kyiv, Lviv, Kharkiv, Kherson and Odesa, knocking out power and water supplies. A missile had hit an apartment building in Kyiv and killed three people. The strikes had also cut the electricity to half of Moldova. Ukraine has been at war with Russia for eight years, since Putin invaded Crimea and annexed much of the Donbas in 2014, and been defending itself against an all-out invasion for nine months, but these attacks are a new development. I showed Oleksandr my phone.

‘Every time I don’t think my hate for Russia can get higher,’ he said.

I stand up, realising I had no idea what it would feel like to be in a blackout. My stomach gnawing at me, for one thing. Remembering in my carry-on bag a Sainsbury’s Meal Deal smoked ham and cheese sandwich, I cheer silently. Eating it helps, and makes me realise how hungry I am. The room is non-smoking, but I open the window on the cold air, light a Cohiba Club and enjoy it to the end.

There is no question of getting undressed to go to bed and I cannot talk to anyone, so I do the only thing I can think of, which is to sit down to write something. I can see to write by balancing my iPhone on the rim of one of the hotel’s glasses, with its torch on. It is surprisingly effective.

Two hours later, I hear a gurgle behind me. Taking my phone torch to the bathroom I try the tap: brown water spits, then more gracefully flows. The power on the air-conditioning unit is also glowing red. I try a light switch. The room explodes into brightness from the cornice lighting. The air-conditioning does not turn on. But things can change in a second.

‘Evans is a wonderful writer and observer, as elegant and gloriously freewheeling as the late Jonathan Raban. Each paragraph has a lapidary charm.’ – The Observer

In 1994, Julian Evans discovered the city of Odesa by accident at the end of a ten-day boat journey down the Dnipro river from Kyiv to Crimea. He fell in love with the crumbling, romantic, piecrust-baroque boom town whose port had been a gateway for smugglers, immigrants, divas and poets for 200 years. Returning five years later, he fell in love with one of Odesa’s women, married her in a monastery opposite the railway station, and began a decades-long relationship with both of them.

Profoundly personal, Undefeatable tells the story of Evans’ involvement with the city over nearly thirty years, living in the formerly Jewish and criminal Moldavanka neighbourhood that Isaac Babel made famous in his Odesa Stories, and of his life with his Ukrainian family. But when war comes with Russia’s seizure of Crimea and the Donbas in 2014, he discovers that his wife Natasha’s parents have stopped speaking to each other because they are on opposite sides of the conflict.

RECOMMENDED:

JULIAN EVANS ON PROSE STYLE

In your early writing career, did you ever consider not working hard on your sentences? Were there writers whose sentences permanently affected the standards of your reading and your own writing aspirations? Has your tolerance for less polished prose decreased over time?

No. For years, writing was a deadly secret that I kept to myself. Well into my early twenties, I knew that I wrote “well but badly”, with a long-winded, multi-clausal pomposity that probably came from writing school and university essays. Practically speaking, my writing life has been dedicated to showing that windiness the door, as much as I can.

I was helped, I think, early on, by working as an editor at a publishing house. I had to write blurbs for the books I edited, and I took huge pains over these 250-word pieces because I knew that a blurb has to make a book come alive. So fairly early I sensed that writing wasn’t so much about expressing myself. I felt it was more about making words conjure up life, some vivid sort of picture, in a reader’s mind, and doing that in the shortest number of words.

That apprenticeship still goes on in my head. I owe some of my first debts to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. I started out thinking Hemingway the better writer, rarer, more laconic, and Fitzgerald the more frivolous. Now my view isn’t quite the reverse, but today I reread The Great Gatsby and find a massive injustice in my first judgment: Fitzgerald has paragraphs in that novel and others in which, from first to last word, I’ll never understand how he achieves what he does.

Some other writers I consider members of my invisible team are Norman Lewis, Sybille Bedford, Graham Greene, Stephen Crane, and the French novelist Michel Déon, who once gave me an excellent bit of advice that is always tucked away somewhere close to the front of my brain. “Being serious, and showing it, that’s your enemy.”

In a podcast Substack’s senior staff discussed the consumption of well-written books chiefly as a form of social posturing, and wondered how they might facilitate this in Substack’s design. Are prose snobs just plain old snobs?

A reader who buys or reads a book to associate themselves with it definitely needs a therapeutic intervention. A writer who writes finely for the sake of it is likely an equal snob. Good writing, beautiful prose, is something else. Richard Ford said that one of the pleasures of reading a novel is becoming suffused by its language. But I think he means that there are two things involved there, the novel and the language, and it’s through the language that you reach the best experience of the world the writer wants to show you. Because every good book is a new world, entire of itself as John Donne would say, and not an adjunct to this one.

What do you understand by the terms substance and style? How have these understandings influenced your prose in Undefeatable?

I start out by having a more or less vague idea that there’s a story to be told, about a place or a person or a situation. The next thing is that I start searching for the way it can be told. I suppose I regard the story as “substance”, and then there are two ways in which it eventually gets told. One is in the style, all the ways you use language, and the other is the form, how you organise its telling. Form to me is at least as interesting as style. The form a book takes usually unlocks its style for me.

I try with each book to find a new, which means less boring, way to tell it. For instance, I wrote my biography of Norman Lewis, SEMI-INVISIBLE MAN, from the point of view of a reluctant biographer: I didn’t much want to write a biography for various reasons, but I had known Norman as a precious friend, so I wrote it to stop anyone else writing one. Some of the book was about my dubious feelings about the genre of biography.

When I wrote UNDEFEATABLE, in the beginning I was determined not to write yet another reasonably well-informed “tell” about Ukraine. I decided to make it a sort of mongrel instead, a mash-up of history, memoir, stories, reporting and some analysis. The main different element perhaps was that I risked something by writing an intimate account of my life with relation to Ukraine: love affairs, marriage, fatherhood, being bombed etc. You could certainly call this self-indulgent, but it was also a way of trying to make it real for readers.

When I hit on the idea of using an extended diary form to write it – 25 years of experiences – but framing them in the present, written from the middle of the war, it also liberated the style I could write it in, wrapping up the personal, analytical, historical, immediate elements in the same language. I was lucky suddenly to realise I could write the book like that, sitting in a freezing, dark hotel room on the first night of a blackout in Odesa after a missile strike in November 2022.

If they discuss them at all, writing guides tend to cover the qualities separately and pay minimal attention to their relationship. What have other writers taught you about this relationship, and what have you had to learn yourself?

It’s an instinctive impulse to want to write something fresh whenever you begin, so I try not to think too rationally but just have an ambition to do something different each time. Usually that’s not about the substance, it’s about the way the story is told, the form and style. I read a lot of European fiction: European writers seem to be more comfortable with experimenting with form, so I guess I don’t feel so alone.

When planning Undefeatable, to what extent did you disconnect substance from style? And when editing it?

Another thing about the European writers I read, people like Emmanuel Carrère or Herta Müller, is that they don’t necessarily separate fiction and non-fiction. So they might be telling a factual story but the storytelling impulse is always churning away. What matters is the voice (is that another word for style?) and whether you, the reader, trust it. That’s what I aimed for in UNDEFEATABLE (and in my other books), a voice that could embrace the firm facts and the more liquid stories. An embrace, not a separation. When I edit, what I’m aiming for is honesty – again, not separation – and with it, brevity. The completest picture with the fewest brushstrokes.

Writers sometimes describe the substance of their books getting away from them. They begin the work planning to communicate certain ideas, but then in the attempt to match techniques to those ideas, they find they’ve communicated something very different. Rather than substance shaping style, the work’s style has shaped unexpected substance, occasionally of a transforming nature for the writer. Has this ever happened to you?

Style, or form or voice, always gives a home to the substance. When I feel I’ve found the right one, all sorts of things in the “substance” as you call it can emerge. So yes, potentially transforming, very.

What ratio between writing and editing would you recommend?

Half and half, though I’d call it writing and rewriting.

How close have you come to headbutting your keyboard in frustration at the minuscule nature of the prose issues you were working on in Undefeatable?

Editing, and microscopic attention to prose issues, are one of the few unalloyed treats of being a writer.

What do poor stylists most lack: guidance, accurate self-estimation, or something else?

I don’t know. Perhaps they don’t read enough. And perhaps they’re not willing to despair and try again tomorrow, or wake up in the middle of the night and write down a new version of a phrase. It’s not uncommon for me to write twenty-five versions of a paragraph or a chapter, and probably never will be.

Julian Evans’s Transit of Venus has been described as “far and away the best book about the Pacific of our times”. His Semi-Invisible Man: the Life of Norman Lewis was published by Jonathan Cape/Picador. He has also written and presented radio and television documentaries and writes for English and French newspapers and magazines including the Guardian, Prospect, Times Literary Supplement and L’Atelier du Roman. He translates from French and German and is a recipient of the Prix du Rayonnement de la Langue Française from the Académie Française. He is also a Royal Literary Fund Consultant Fellow. He lives in Bristol and London with his two children.