Booker Prize winner Paul Lynch picks his best-written works of fiction of the century to date

Read the opening pages from his selections below

Welcome to the 1000 new subscribers who’ve signed up this past month for our picks of the best-written works of literary and speculative fiction and nonfiction, and masterclasses on prose style by their authors.

If you’d like a complimentary paid subscription, then simply recommend Auraist on Substack. If your own Substack is likely to interest our readers, we’ll recommend it too.

IN TODAY’S ISSUE

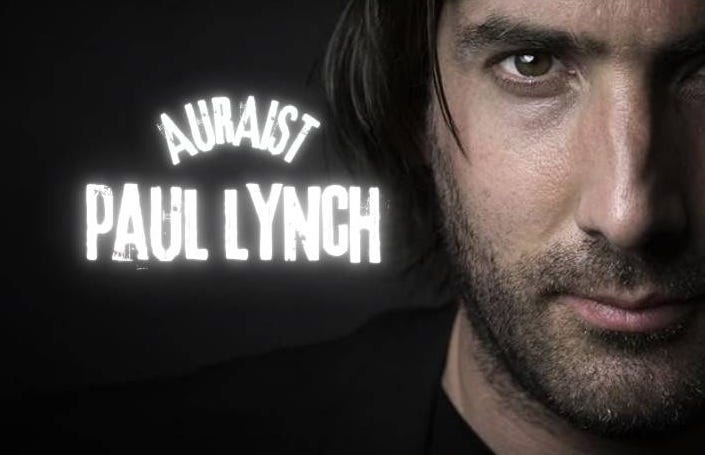

—Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor, chosen by Paul Lynch as one of the best-written works of fiction of the century to date:

‘Hurricane Season reimagines the Southern Gothic in the fallen world that is modern Mexico with writing that sees into souls: the warped psyche beaten out of shape, the psyche devoured by shadow. She is a dangerous writer with enormous ferociousness and integrity. In other words, she is the real thing.’

—The Other Name, the first and second parts of Jon Fosse’s Septology series, Lynch’s other choice:

‘Few writers can break through a stone wall and open a door to a room that was not there before. Jon Fosse is one such writer. Septology will endure as one of the great modern novels for its hypnotic banality, a roman fleuve in unadorned, slow prose that might best be defined as spiritual realism for how Fosse seizes hold of reality while simultaneously laying bare the ineffable wonder.’

Submitting and pitching work to Auraist

We offer writers a fast-growing audience of discerning readers, including many world-class writers, major publishers and literary agencies, and journalists at the highest-profile publications.

The following submissions and pitches are welcome:

—Books published in the last three months.

—Works serialised on Substack.

—Essays on prose style.

—Reviews of a book or author’s prose style.

If you wish to submit or pitch work to us, sign up for a paid subscription via the button below and then email us at auraist@substack.com.

If we publish your work, we’ll invite you to answer our questions on prose style. Your answers will be considered for inclusion in the published collection of these pieces by many of the world’s best writers.

I.

They reached the canal along the track leading up from the river, their slingshots drawn for battle and their eyes squinting, almost stitched together, in the midday glare. There were five of them, their ringleader the only one in swimming trunks: red shorts that blazed behind the parched crops of the cane fields, still low in early May. The rest of the troop trailed behind him in their underpants, all four caked in mud up to their shins, all four taking turns to carry the pail of small rocks they’d taken from the river that morning; all four scowling and fierce and so ready to give themselves up for the cause that not even the youngest, bringing up the rear, would have dared admit he was scared, the elastic of his slingshot pulled taut in his hands, the rock snug in the leather pad, primed to strike anything that got in his way at the very first sign of an ambush, be that the caw of the bienteveo, perched unseen like a guard in the trees behind them, the rustle of leaves being thrashed aside, or the whoosh of a rock cleaving the air just beyond their noses, the breeze warm and the almost white sky thick with ethereal birds of prey and a terrible smell that hit them harder than a fistful of sand in the face, a stench that made them want to hawk it up before it reached their guts, that made them want to stop and turn round. But the ringleader pointed to the edge of the cattle track, and all five of them, crawling along the dry grass, all five of them packed together in a single body, all five of them surrounded by blow flies, finally recognized what was peeping out from the yellow foam on the water’s surface: the rotten face of a corpse floating among the rushes and the plastic bags swept in from the road on the breeze, the dark mask seething under a myriad of black snakes, smiling.

COMING SOON

—More of the best-written recent releases.

—Kia Corthron, A.L. Kennedy and more of the world’s best writers answer our questions on style.

—The best-written works on the shortlists for the Gordon Burn Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Awards.

A paid subscription to Auraist gives readers access to our full archive of dozens of author masterclasses on prose style, hundreds of picks from recent releases and prize shortlists, the best-written books of the century, and extracts from many of these. Or you can join the 32K readers who’ve followed us or subscribed for free access to posts for a fortnight after publication.

RECOMMENDED

I

And I see myself standing and looking at the picture with the two lines that cross in the middle, one purple line, one brown line, it’s a painting wider than it is high and I see that I’ve painted the lines slowly, the paint is thick, two long wide lines, and they’ve dripped, where the brown line and purple line cross the colours blend beautifully and drip and I’m thinking this isn’t a picture but suddenly the picture is the way it’s supposed to be, it’s done, there’s nothing more to do on it, I think, it’s time to put it away, I don’t want to stand here at the easel any more, I don’t want to look at it any more, I think, and I think today’s Monday and I think I have to put this picture away with the other ones I’m working on but am not done with, the canvases on stretchers leaning against the wall between the bedroom door and the hall door under the hook with the brown leather shoulderbag on it, the bag where I keep my sketch-pad and pencil, and then I look at the two stacks of finished paintings propped against the wall next to the kitchen door, I already have ten or so big paintings finished plus four or five small ones, something like that, fourteen paintings in all in two stacks next to each other by the kitchen door, since I’m about to have a show, most of the paintings are approximately square, as they put it, I think, but sometimes I also paint long narrow ones and the one with the two lines crossing is noticeably oblong, as they put it, but I don’t want to put this one into the show because I don’t like it much, maybe all things considered it’s not really a painting, just two lines, or maybe I want to keep it for myself and not sell it? I like to keep my best pictures, not sell them, and maybe this is one of them, even though I don’t like it? yes, maybe I do want to hold onto it even if you might say it’s a failed painting? I don’t know why I’d want to keep it, with the bunch of other pictures I have up in the attic, in a storage room, instead of getting rid of it, or maybe, anyway, maybe Åsleik wants the picture? yes, to give Sister as a Christmas present? because every year during Advent I give him a painting that he gives to Sister as a Christmas present and I get meat and fish and firewood and other things from him, yes, and I mustn’t forget, as Åsleik always says, that he shovels the snow from my driveway in the winter too, yes, he says things like that too, and when I say what a painting like that can sell for in Bjørgvin Åsleik says he can’t believe people would pay so much for a painting, anyway whoever does pay that much money must have a lot of it, he says, and I say I know what you mean about it being a lot of money, I think so too, and Åsleik says well in that case he’s getting a really good deal, in that case it’s a very expensive Christmas present he’s giving Sister every year, he says, and I say yes, yes, and then we both fall silent, and then I say that I do give him a little money for the salt-cured lamb ribs for Christmas, dry-cured mutton, salt cod, firewood, and for shovelling the snow, maybe a bag with some groceries that I bought in Bjørgvin when I’ve gone there to run an errand, I say, and he says, a little embarassed, yes I do do that, fair’s fair, he says, and I think I shouldn’t have said that, Åsleik doesn’t want to accept money or anything else from me, but when I think about how I have enough money to get by and he has almost none, yes, well, I slip him a few more bills, quickly, furtively, as if neither of us knows it’s happening