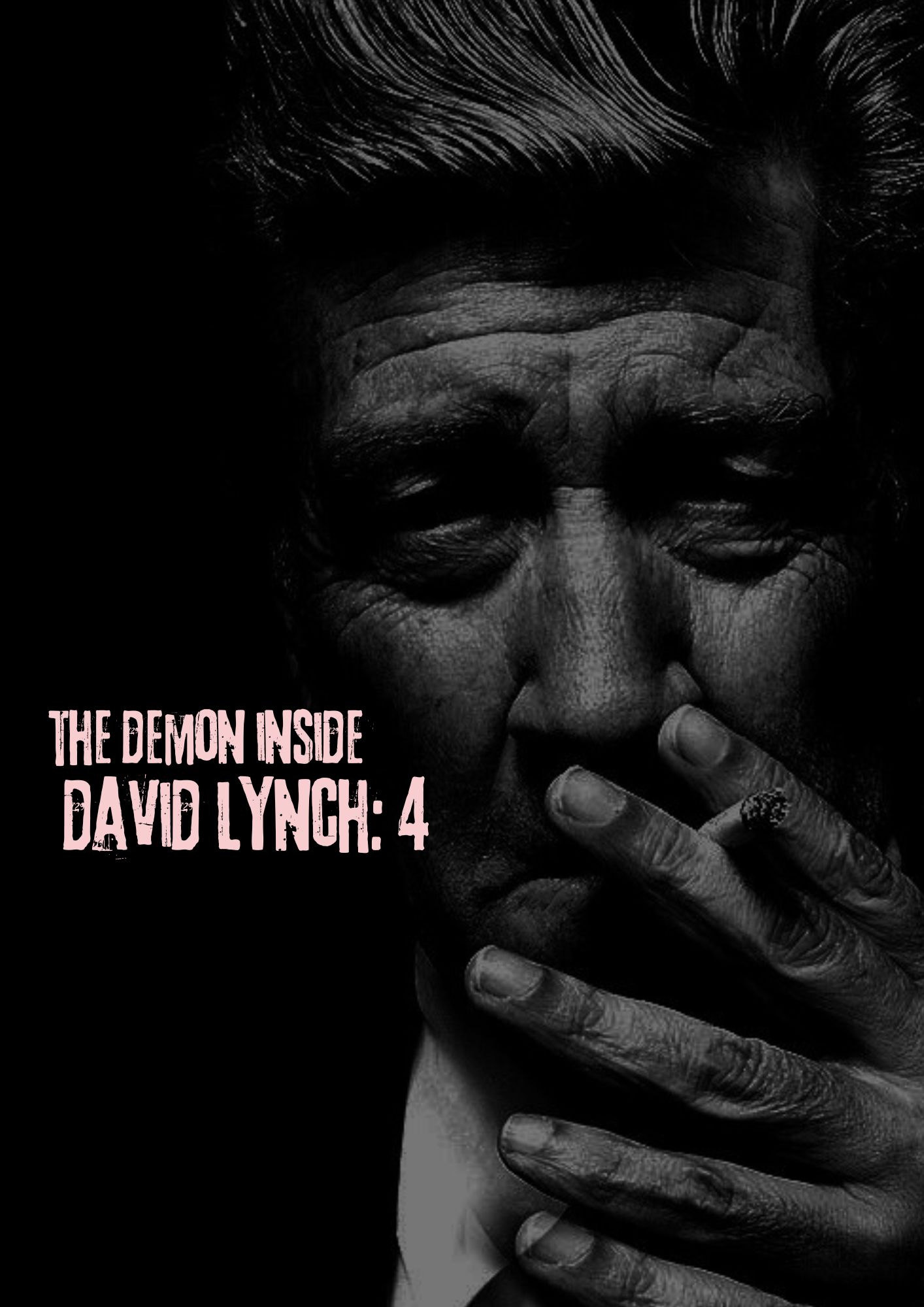

The Demon Inside David Lynch: TV Drama's Worst Fiasco 4

Abasement and Contempt ^ Research Chemicals ^ Rampant Cheesiness ^ A Festival of Fetishes ^ Unyoung Nathan Barleys ^ Mike Pences with Greying Waxed Moustaches: A Case Study

The Demon Inside David Lynch states that the celebrated director was possessed by a ten-dimensional entity that went on to make Twin Peaks: The Return. You won’t be surprised to hear this is fiction, satire.

Chapter 1 is here.

The Return Part 11: a box is delivered and opened in brushland

Abasement and Contempt

ONE OF CÉSAR’S DEFENCES of Cooper’s time travel and the retcon went like this: The series doesn’t actually approve of his journey back in time to erase everything that precedes this—it is shown to be a bad lifechoice with unforeseen repercussions. This too ties in with one of the series’ most important themes: anti-nostalgia, anti-retro, don’t look back.^^

However, it’s not just Cooper who enacts the retcon. It’s the series itself. If halfway through Vertigo Scottie travels back in time and murders Madeleine/Judy and therefore wrecks the audience’s experience, it doesn’t make it okay if the film then indicates that doing so was a mistake. In this case the film wasn’t ruined by Scottie but by Hitchcock.

A minging artistic choice isn’t okay if the artist agrees it’s minging, just as a relapse isn’t okay if the relapser knew it would be disastrous. A trainwreck in which the driver deliberately crashes the train is still a trainwreck. Many big-tent films feature effects and moments of spectacle that in no way compensate for the contempt for the audience and the sense that nobody involved cared about the events or characters, and you’d hardly say these projects haven’t been committeed to lowest-common-denominator sludge. Every last thing onscreen is deliberate. But this doesn’t excuse how bad they are, and it doesn’t excuse The Return either. I’m probably overexplaining this. You already know this stuff, surely, and would never have considered anything else.

A linked defence from certain Manbuns goes like this: Yes, the time travel and Green Glove versus BOB and plenty of other scenes are kind of iffy. Still, they’re kind of punk as well, yeah? Kind of masterly trolling of the audience. Season 3 was a five-month trolling session, which justifies all the iffiness, yeah?

Much of the response to the previous defence applies to this one too. Just because your mince is deliberate and punk doesn’t make it okay. Sid Vicious taking a bike chain to the journalist Nick Kent may or may not have been punk, but it was hardly commendable. And we shouldn’t have to point this out, but there’s a reason nobody’s ever made an eighteen-hour punk track.

The Return’s nearest musical equivalent, Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, is sixty-four minutes of listener-goading kookiness. The verdict of Reed himself was that ‘anyone who gets to side four is dumber than I am.’ You might want to put yourself through a track from it sometime. Picture César listening closely to every one of its droning minutes. Picture the galoot fiddling with the waxed ends of his moustache, puffing meth, and telling himself he’s enjoying what Reed’s served up.

Metal Machine Music is kind of punk and also unlistenable mince, yet even its tracks are only sixteen minutes long. They don’t last an hour like episodes of The Return. As with every other form of provocative so-bad-it’s-good, punk and trolling only work in relatively short bursts.

And they work best in the young. César slumped in alcoholic blackout at a family gathering and snarling at invisible persecutors looks worse, is worse, than the same from his chiselled-cheekboned nephew.

It should be said that we eventually guessed the showrunner, Mr Lynch as we wrongly believed at the time, the hermit or Dr Evil as we now called him, would pull some kind of stunt in the finale to retrospectively sabotage the rest of Twin Peaks. Waiting for that finale was like waiting throughout Se7en’s final scenes for John Doe to complete his horrorwork. Here comes the delivery van. You wonder what might be inside. With a growing sense of dread you think back over your twenty-seven-year history with Twin Peaks. You remember Laura’s dead body wrapped in plastic. Your birthday party in the woods, and the next day when you thought you’d solved the mystery of who killed her. The consummate Episode 14 when it’s revealed it was her father. Fire Walk with Me’s peerless portrayal of incestuous abuse.

Then you remember the antipathy for the audience and for Twin Peaks nostalgia throughout The Return. Now you know what’s in the van. The entire story never happened. Who killed Laura Palmer? Nobody did. None of it happened, sucker. How else was this farce ever going to wrap up?

This link between its audience-trolling ending and Se7en is made explicit in Part 11 when a mysterious box is delivered and opened out in rural brushland. When we became the same consciousness, the Twin told me this box was one of many such trollings of its cultist marks like César. The galoot then lapped this up and declared it yet more evidence of the auteur’s genius. Which the Twin knew he would and disliked him for in advance. It therefore felt no guilt about using him and other Lynch cultists as dupes in the entities’ masterplan, and as we’ll see planted more jokes about this. Which the Césars misunderstood and instead declared yet more evidence of genius. This is a fairly advanced state of submissiveness, equivalent to those reduced to degraded wretchedness by sissy-hypno porn.

And the abasement never ends. Whether with The Return and its Césars or with fascist leaders and their cultists, the trolling and abasement, contempt and acceptance or welcoming of that contempt, they never end. Not until a rock bottom comes along.

Art by Compusician

Research Chemicals

[Ella]

THE SUBSTANCES which for better or worse I got Andy into, they are not against the law here in Spain. They can be magical, some of them. I might not now share them with people that are in recovery for alcoholism, but even someone as dejected as Andy often was only had problems with them when he tripped more than once a month and did not rotate the substances.

1. 225 ug oral of the LSD analogue AL-LAD. This drug opens up in you classy and mature emotions, unearthly emotions. They are then potentiated by visions of gods and goddesses and god/desses so keen on knowing you, so in your face and every other part of you, that they would be a little frightening if they were not so graceful and classy about it. Hardly ever pushy or hectic, nearly always sagrado, elegante, just on the right side of dirty-tasteful.

2. 20-30 mg oral of 4-AcO-MET or 4-HO-MiPT. These are analogues of magic mushrooms which among their best qualities maximise those of AL-LAD, including the beauty of the little deities. Both are highly stimulating, engrossing and charismatic. If Javier Bardem was a research chemical I think that he would be 4-AcO-MET or 4-HO-MiPT.

But you must not confuse these little beings with the entities. They are much more beautiful than the entities are but you cannot become one of them, or at least I never have. And you hardly ever forget that they are hallucinations. The twiddlers of knobs, on the other hand, the entities, they are realer than real.

These three drugs so evolve and deepen your feelings that you can become highly emotional more often than before, even when you have not had them for weeks or months. Which may explain in part the strength of emotion we see in this story from Andy, and also the melancolía in him which he does not like to speak about, and how all of this affected the direction the story took. The truth is I often wish I never shared these drugs with him.

3. 75-150ug oral of the LSD analogue ALD-52.

4. 60-120mg oral or 30-70mg snorted of the MDMA analogue 3-FEA.

None of these chemicals shows you the entities. For this you need to take the famous psychedelic DMT, which is not usually called a research chemical, because it has been used for centuries. The only drug which does not only allow you to meet the entities but become one of them is Tsarbomba, also called 8-BOM-DMT. This substance is available on research chemical sites and also exists inside many plants and animals. It allows you to become an entity by somehow wiping away the illusion that you are not one, that you are one thing and not any other.

Among the best books on these two psychedelics are the inspirational novel-memoir by Rob Doyle called Threshold, Sancia Ignacio’s award-winning Tsarbomba: La molécula milagrosa del espacio (Tsarbomba: The Miracle Molecule from Space), Rick Strassman’s DMT: The Spirit Molecule, and his DMT and the Soul of Prophecy, which draws parallels between the entities and the supernatural beings which are in the Bible. Ignacio has established beyond dispute the release of Tsarbomba in the human pineal gland at moments of intense stress, and also when you are born and when you die.

What you do not just understand but act out in the later stages of Tsarbomba trips is that the entities have it wrong with their ‘Argument leading to the Promised End’ approach. Very wrong. They think that they have a job they must do to bring about this Promised End, which they believe will happen at some point in some future they imagine.

But the fact is the Promised End has already happened. It is forever already happening, as are the projects the entities engage in to supposedly bring it about. What Tsarbomba lets you see is that from the perspective of fifteen dimensions and more, time stops being time as we humans understand it and becomes simply one among directions without number which are already written down in (gem)stone. Like professional wrestling, the Ultraverse is a narrative which is unscripted and unpredictable only in the way it appears. In reality it is more similar to a perpetuo Diamond of consciousness which never changes, with facets in infinite numbers and also dimensions in infinite numbers from where they come. It is this Diamond which you become on a Tsarbomba trip, as well as becoming entities and going to heaven.

These trips are quite heavy, then, and you might describe them as like 4-AcO-MET to the power of DMT. I have only had a few experiences of this type, at most perhaps a dozen. Andy has only had the trip he had in May 2024, which was brought on by pineal Tsarbomba due to an acumulación over years of stress and melancolía related to David Lynch. Also to me, no doubt.

The drugs I have mentioned here, which together make up the most advanced transport network the Diamond has for humans, they allow you to comprehend the mysteries of death and other matters. They just do. If you have a problem with this then you need to bring it up with the Diamond.

Especially on Tsarbomba everything sparkles with a clearness which gets into all of your perceptions. This clearness cleanses them of, as Andy put it, ‘shoddy slacker loser mark faux-naive faux-humble dopiness’. Things are seen in the interior way you see them in your dreams or when you are in love, with a UHD trueness which lets you forget their encarnación in shapes and behaviours which you approve of or do not. You perceive their real inner sides, and their shells as simply form, just an accident of glassy, swirling Lines. They lay aside these shells and remain only as their essence, their actual being as the entities see them and as wonderdrugs and loving provocativos security guards let you see them, without limits or names.

Face of stone

Rampant Cheesiness

A USEFUL WAY TO VIEW The Return is that except for some of Parts 3 and 8 it’s a severe instance of cheesiness. Had Andy Warhol risen from the dead and made the series he’d probably have given some lines to gay characters and maybe wouldn’t have mentioned his risen-corpse’s erections, but he might well have given us similarly ill-conceived, poorly scripted, poorly lit, farcically acted, farcically paced, dead-air-filled, incoherent, rampant cheesiness.

The original Twin Peaks was deliberately cheesy at times, but this was more than balanced out by its scenes of terror, pathos, and generosity—its sincerity. The Return, however, is deliberate cheese from the highest level to the lowest. It doesn’t just feel rotten but comprehensively, methodically so. Almost every important artistic decision in almost every episode has been informed by a sensibility that wallows in corniness, artifice, frivolity, over-the-top gimmickry and flamboyance, and just plain wrongness. The retcon, all that’s happened then turning out to be some guy’s dream, and the giggles at characters’ torment are the sort of trash thrown up by an aesthetic of childish cheesiness and other so-bad-it’s-good. The boggingness of the series nearly always appears to have a titter behind it regarding any unzany expectations from its audience. That titter is the cheesy sensibility.

Men like César did manage to watch it in a spirit of so-bad-it’s-geeenius, because these men love their cheese. So do fashion students, installation artists and similar types whose tolerance for The Return was far higher than average. Because the fact is that many people don’t enjoy cheesiness, let alone seventeen hours of the stuff. Les says it reminds him too much of relapses, of knowing the urge is idiotic, immature, corny, crosses a Line, but acting on it anyway.

I don’t find a lot wrong with provocative so-bad-it’s-good in reasonably sized doses. Just before I quit the drink a crew of us found ourselves in Villa de Vallecas in a pretty rough club. We’d been wasted for hours and when the DJ played Pharrell Williams’ ‘Happy’ César jumped up on our table to dance and wiggle his buttocks in my face. It was funnyish in a daft, messy-all-day-bender sort of way.

Then he approached the table of some nearby growlers. He jumped onto it and wiggled his bottom near the growlers’ faces. Drunkenly purple-faced growlers, six of them.

They took his provocations well. Some got up to dance below him while others pretended to fondle his wiggling buttocks. When ‘Happy’ ended and the DJ played Kylie’s ‘I Can’t Get You Out of My Head’, César decided to keep dancing up there on that table.

Now no purple-faced growler was pretending to feel his buttocks. But he continued to dance and wiggle them in their faces.

César needed fifteen stitches in his own face that night. His bottom has, I suspect, never since been planted in anybody’s face. The point being, again, that inflammatory so-bad-it’s-good requires discipline. (César and the growlers are a handy metaphor for other things as well, e.g. a few of our major political and cultural woes).

However you look at it, The Return is the unfunniest work of the last 300,000 years. If you doubt this it’s likely because you’ve never watched the series, which has more moments and touches that are supposed to be funny but aren’t than anything else ever made. It also has a higher ratio of attempted-funny to actually-funny, somewhere in the high three figures. The thing also sinks remarkably low in its hunt for laughs, yet has a high conceit of its funniness.

You know when you watch a stand-up comedian lose their touch but keep plugging away until they’re right down there with the desperate throbbers wisecracking about wheelchair access, obescity, and trans-rape, yet carry themselves as though they’re Bill Hicks? This feels similar but many times worse.

It was an element of The One that really desolated Ella. After we watched its unfunniest episodes, grappling with my own One became for days gynecologically impossible. Ella’s position, or more like her certainty, was that there won’t ever, not on Earth, not anywhere in the Ultraverse, be a work with a greater gap between attempted-funny and actually-funny, which I must say was a little presumptuous of her. Nonetheless, the show is aeonally unfunny, and has hours of dead air to help you experience this to its full shoe-wrecking, grappling-wrecking extent.

Even leaving aside all its other defects, its unfunniness alone would make it the worst art project of the century. There can’t be many works in history so unfunny they delay your grappling by half a week, bring a hot lump to your throat, and make every atom of the cosmos feel like it’s quietly snarling with malevolence. That’s a whole different level of unfunny to The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas or The Boat That Rocked.

In fact we’re in the same situation with unfunny as we were with awful. We need a word more terrorised, more Lovecraftian, to accurately describe the savagery of the series’ onslaught of failed humour. To convey those fogbanks of supernatural sorrow and despair the two of us used to feel in our skulls, whatever room we were watching in, and the universe itself. Fogbanks whispering of a quick mutual wrist-slash in the bathtub to bring the onslaught to an end.

There is a moment in The Return that we did find inanely funny, though, just about. This is out of hundreds of attempts at such humour, true, but even so it’s not completely unfunny when FBI Deputy Director Gordon Cole looks at a photo of Mount Rushmore and says, ‘There they are, Albert, faces of stone’, and soon afterwards we get close-ups of Cole’s craggy face.

Now fair enough, a segment that makes viewers appraise the writer-director-producer-star-hermit’s own face, with more than enough time for sketching the hermit’s features, is still pretty bad. And ‘faces of stone’ does equate Cole and the auteur self-cast in the part with some of the greatest US presidents in history. It is therefore yet another twinkle in the constellation of egomania that attends this character and self-casting^^. That said, the line and close-ups are still in the outreaches of funny, more or less. They don’t quite bring on, as do those hundreds of failed attempts, tightly clamped body parts, lumpy throats, wrecked shoes, and existential heebie-jeebies.

An instance that had César gleefully scattering phlegm and meth crystals around his security hut as he watched on his phone is the scene in which the Alex Jones/Neil Breen parody Dr Jacoby, played by Russ Tamblyn, spraypaints shovels gold and leaves them hanging up to dry. The joke here is an acknowledgement that The Return is so tedious it’s similar to watching paint dry. (And we’ve already endured the young lovers Sam and Tracey, played by Benjamin Rosenfield and Tracey Barberato, tediously watching a glass box in which, like the show making these jokes about its own tediousness, nothing of interest happens). You get the joke. You rub your sinuses or toes. Then the show keeps tediously repeating this latest tedious joke on the subject of its own tediousness as more and more shovels get painted, and you start wondering where Ella keeps her razor blades.

As with much of this series it resembles the worst conceptual art. You get the concept. It’s hoachingly self-involved and not particularly interesting or witty. The concept gets repeated César’s-buttocks-style, and César types rhapsodise over it while you yourself feel little but irritation at the artist for wasting your time.

And even if those hundreds of attempts hadn’t failed, persistent cheesiness for hours and hours is highly unlikely to make a decent work of art. Nearly twenty hours of full-on cheese are very hard going, because past a point so-bad-it’s-good becomes so-bad-it’s-goading, as those growlers and César will confirm.

It doesn’t matter if you want to pastiche a soap opera from thirty years ago or whatever other mightily relevant foe you have in your sights. Or to portray temporality as a Möbius strip, or to follow some other ‘idea to the end’, as Mr Lynch often put it. Some ideas shouldn’t be followed to the end, because they’re cheesy garbage. Two of these are clearly Cooper’s zip back in time to rescue Laura, and it all turning out to be Richard’s dream. The Twin knew exactly how garbage they were and that’s why it jumped in with both demonic hoofs.

A Festival of Fetishes

WE NEED TO GET OUT OF THE WAY the Greying Manbun argument that people hate The Return because they wanted it to resemble the original Twin Peaks. If throughout its style had resembled the 1945 atomic-explosion and 1956 menacing-Woodsmen sequences in Part 8, its only genuinely radical episode and the one furthest from the first two seasons, most haters would have been as happy as the Manbuns.

Those sequences are like the Manbuns claim some of the finest television ever broadcast. High stakes allied to likeable or fascinating characters, engaging story developments, gorgeous visuals and sound design that result in a spell being cast, suspension of disbelief and the viewer’s submergence in the unfolding dream, leading at last to a sense of what we’re watching actually mattering—Part 8 is the hole-in-one that makes the 1000+ score for the eighteen-episode production all the more remarkable. It’s the one episode not dominated by cheesiness, and in a counterintuitive way we’ll look at later on, its very excellence is key to the Twin’s project of making the worst piece of art ever seen.

Suspension of disbelief, a core marvel of fictional narrative, does occur when you watch The Return but only in the case of most of Part 8. Of the remaining 960 minutes or so, our belief was suspended for precisely none. The fourth wall isn’t so much broken as barely constructed in the first place. The series’ prevention of suspension of disbelief throughout those minutes is unmatched in TV drama.

This prevention is ensured in a number of ways, each of which would likely have achieved it by itself. For a start, suspension of disbelief is made impossible by rampant cheesiness. When so many elements have an undercurrent of Look how silly this show is! Creators, actors, crew, viewers, aren’t we all being just outrageously naff? Imagine anyone being crass enough to fall for any of it! we are liable to take them at their word and see not characters and events we can believe in and care about. Instead we see droves of boomer and gen-x actors being silly and naff for scene after scene, hour after hour for five months. And as with many purveyors of in-your-face cheesiness, offputtingly self-pleased. The effect’s a little like those invasions of early-‘70s TV chatshows by mobs of hippies who flicked the ears and mussed the hair of the presenters and guests and studio audiences, and sang nursery rhymes and threw Dayglo paint around, except in this case many of the goofy self-pleased self-ironists are nearer eighty than twenty.

Suspension of disbelief is also made impossible by the greatest drama of the decade’s rampant contempt and ultimate kookiness. So much misanthropy allied to more or less nonstop extreme peculiarity prevents what’s onscreen being a world you can believe in. And the fact that it’s a world you cannot believe in makes the misanthropy seem even worse. This misanthropy has nothing persuasive about it. No attempt is made to justify it. All you get is a reclusive showrunner exhibiting contempt for dozens of different types of people and not caring how valid the people watching find this. The human race is frequently risible or despicable and that’s that, the series informs us, and the humans watching just have to accept it.

Meanwhile the ultimate kookiness prevents this being a world you can believe in and is itself made even more repellent by the very implausibility of this world. Unlike in Lynch’s mid-career works, there is no attempt to make the strangeness appear believable. No effort is made to cast an artistic spell in which we’re at first shocked by the strangeness but then in time persuaded that events could indeed unfold this way. All we get instead is implausibly extreme zaniness after implausibly extreme zaniness for nearly as long as our world takes to rotate on its axis. And apart from Tim Kreider no one’s suggested a non-demonic rationale for the extremity, even compared to the zaniest previous major works of Mr Lynch.

The acting also ruins any chance at suspension of disbelief the way it does in a bad school play. Jim Belushi’s stated that he had no idea what was going on in his scene in the sheriff’s office where Green Glove defeats BOB, and throughout the series similar confusion is evident in many of the other actors.

Then there’s singer-songwriter Chrysta Bell’s casting as FBI Special Agent Tammy Preston. This top crimefighter is portrayed as never less than impressed by a handsy boss more than twice her age, the auteur-played Gordon Cole who leers at her buttocks as she slinks away in high heels, etc. In the finale Tammy’s face is edited in to provide a not unimpressed reaction when in one of the Twin’s many cruel jokes, this time mocking Mr Lynch’s bodily and volitional impotence, Cole declares in an FBI office that he’s not soft ‘where it counts’. This remark had Stanley the Rottweiler rolling around on Ella’s floor whimpering.

Bell is a talented musician but not a talented actress. There are dozens of weak performances in The Return but Bell’s has unsurprisingly drawn the most criticism. It’s maybe not quite porn standard, or Chica standard, but it is worse than you’d witness in many secondary-school plays. Nearly every time she’s onscreen she appears flummoxed, out of her depth, a benzo’d trout in a hall of mirrors. Bell has a pouty and sultry way of talking in interviews about her music and attempts the same pouty sultriness in her lines as FBI agent Tammy. But she doesn’t only come across as pouty and sultry. She comes across as baffled, contrived, self-conscious and spaced-out—that is, the way you or I would come across if we suffered the degradation of being cast in a TV drama broadcast across the world. It’s unpleasant to watch and brings to mind Citizen Kane’s opera-ruining mistress. The Return is a disaster not just because it drags and looks ugly and the dialogue mings and so on, but because throughout there are also these intimations of demonic cruelty.

Persistent refusal or breaking of suspension of disbelief was once a worthwhile technique for narrative artists, if the payoff was sufficient. Yet the last time that was really the case was decades ago, and the Twin designed the show to con everyone into thinking former ‘60s student David Lynch chose to stuff it with flogged-to-death ‘60s-filmschool silliness.

This helps explain the show’s oddly Austin Powers feel. Mr Lynch is left resembling a postmodernist Dr Evil who’s travelled forwards decades in time and announced not a demand for ‘One million dollars’ but rather his breakthrough of ‘Deliberately poor acting. Get a load of this, world: I’m going to prevent suspension of disbelief.’

Despite what the Césars claim, The Return as a whole is not an avant-garde work. It’s as obscurantist, transgressive and soporific as the worst artschool installations. Apart from the cosmic-ocean parts of the third episode, though, and the twentieth-century parts of the eighth, there’s little freshness, or at least little we can admire. Instead what we get are this hermitic Dr Evil’s rehashes of ‘60s-filmschool so-bad-it’s-good like deliberate cheesiness, zaniness, poor acting, boredom, transgression, and refusal of suspension of disbelief.

Which would matter less if this refusal did not sacrifice one of fiction’s finest effects. Suspension of disbelief is a sacred function of narrative art, like tonality in music. It also has a curious similarity to the recovery maxim fake it till you make it, the idea that newcomers should turn up at meetings and pretend to believe the cult-like dogma and gibberish on display, as they see it, until one day they find they’ve cleaned up their act and become a believer.

And suspension of disbelief is difficult to achieve to the extent that Mr Lynch managed earlier in his career. At his peak he wove dreams that suspended our disbelief more effectively than nearly anybody else. This was all the more impressive considering the abnormality of the portrayed worlds and psychic states. Big Fish indeed, to quote Lynch himself, especially compared to the fousty tiddlers of po-mo conceptualising. Artists who mess with this too much are therefore playing a riskier game than many of them appear to realise. To make it worthwhile they had better be cooking some tasty and nutritious Big Fish.

Many of us struggle to suspend our disbelief in fictional narratives these days, for reasons that haven’t yet been established or even that widely addressed. One factor has to be the web, what Ella called el zumbido, the drone. If you spend your time online routinely maintaining your disbelief against perhaps the most powerful lie-machine ever invented, your mind will likely find it difficult to change gear for fiction and suspend that sanity-preserving maintenance of disbelief.

Nevertheless, some of the best shows and films do still manage to get us over this hump by working hard at doing so. The Return, though, doesn’t even try. The result is that yet again Mr Lynch is made to look a classic male boomer balloon lost in and therefore sunk by his fetishes and compulsive brooding about them.

Because what happens to a work of fiction when suspension of disbelief is banished? What are we left with if we are seldom allowed to pretend the events or characters are real? We’re left with little but the accumulated opinions, fetishes and speculations of the artist.

This does not reflect well, to say the least, on David Lynch. The bloke ends up looking as though he was given an enormous budget by Showtime to make a third season of Twin Peaks with storylines and characters the audience could engage with, but instead served up a five-month Festival of My Godly Yet Curiously 4Channish Fetishes About My Career, My Penis, Hot Young Chicks, Hags, the Comic Potential of Disabled Men Tied to Chairs, Pam Ewing’s Dream in the 1986 Season of Dallas, Time As a Möbius Strip, Nuclear Warfare, and You Unevolved Lowlifes^^ (see Part 5).

Nathan

Unyoung Nathan Barleys

THE KIND OF MEN who applaud the rampant cheesiness, ultimate kookiness, the retcon, and the giggly climax to the BOB storyline, and plenty such cultists exist—César called the latter his favourite moment in screen history because it’s so punk—these men have been numbed and beguiled by their Master so far out into the wilfully perverse periphery that they’ve lost their moorings.

Talking about the original Twin Peaks was sometimes a good way to click with new people you met socially. The same is unlikely to be true, however, of chat about the comic value of The Return’s worst transgressions. Anyone who doesn’t have a problem with these, let alone praises them, is a lost cause and best avoided until they come to their senses. Picture timeworn Nathan Barleys in low-bummed, cropped drainpipes, and greying manbuns. Picture these boulevardiers as they snort with 4channish laughter and joyfully squeal along to the banal ‘Charmaine’ and the dozens of repetitions of ‘Hello Johnny. How are you today?’ while Johnny experiences suffering beyond most people’s imaginings. These boulevardiers don’t just have a niche sensibility. They are at best victims of cult propaganda and at worst repugnant.

Despite his curiously young looks, enhanced by his pageboy haircut, Les has pretty much seen it all. Kirkdale childhood with violence from both parents, months of the DTs, struggles with overeating, gambling, hookers and porn, hospitalised several times for acid overdoses and nervous breakdowns, jailed several times for fraud and sudden grappling, plus years in the Army in Derry, Amarah and Basra. Plus brothers, sisters, wives and children who haven’t spoken to him for decades, and dozens of friends’ suicides and relapse deaths throughout the eighteen years he was sober and nonwrestling until the abomination came along.

He’s one of the laziest people I’ve known, and probably the soundest, the nearest I’ve come to a hero I actually know. And I have seldom met anybody so unwilling to make even the slightest attempt to fake interest in worldly matters like work or romantic intrigues, gridlock and call centres, that have other people in tizzies.

Nonetheless, this chilled-going-on-lackadaisical Grapplers Anonymous sponsor despised The Return more than I ever did. (He has arthritis as well, which the show’s many toe-curlers and ankle-curlers weren’t helping). Not once did he hit me with the abuse Ella later did about my obsession with it (Part 7), because in contrast to Ella at that time he knew not to underestimate the horror we were facing. Even the normally placid Stanley was traumatised by the show, and would bark his big head off whenever the Demonic Twin, or Mr Lynch as we believed, appeared onscreen as Gordon Cole.

Les will sponsor anybody no matter their personality or background, and encouraged me to stick by Trinna despite her politics and Satan-worship. Yet even Les’s patience can run out with bohemian blokes in recovery, who have among the highest rates of relapse of any social group.

One reason for this is they believe, many of them, that the best preparation for life’s toughest tests is the arts. Novels, films, TV shows, gigs, recitals, albums, and installations are where they believe the world’s really helpful wisdom lies. In their usual bleary-eyed half-baked drowsy way, that’s what they vaguely reckon might see them through life’s trials, the wisdom and life-tools on offer from directors, choreographers, violinists, and conceptual artists who went straight from relatively cushy upbringings to arts careers and have seldom if ever worked outside the field.

A curious feature of most films, TV dramas, and many novels is that they revolve around tough moral quandaries, despite how irrelevant these are, largely speaking, to their audience. The people I know, addicts or not, have a genuinely crucial moral quandary to weigh up a couple of times a decade tops. Their primary problem has not been quandaries, having to choose between similarly compelling courses of action, but instead two opposite forms of certainty. Either the full-steam-ahead blind lunacy of denial, as in a supervisor who complains about climate-change denial but denies there’s anything wrong with spitting near his colleagues’ faces, or as in a boulevardier hooked on meth; or the dismal stuckness when you know fine well the right course of action but just can’t take it, as in a boulevardier desperate to stop doing meth, or as in most people faced with climate breakdown. Yet you see works with these two issues far less often in the mainstream arts than those with protagonists torn between e.g. saving their marriage and saving the world. These are as relevant to the people watching or reading as quandaries about whether or not disabled men’s degradation is amusing.

Presumably one reason these works lack such issues is that they’re usually made by multimillionaires with support networks that help them avoid wrecking their lives and careers in the insanity of denial or pathological sloth. Which is nice for them, obviously, but it hardly equips them as guides to living for the rest of us.

‘Pain is concentrated information,’ as Les puts it, ‘and hardship can breed wisdom, and is among the very few things which can do this, meaning folk that have seldom struggled often aren’t much help to them that have.’ (Obviously Les is generalising here. As we’ll see in Part 8, a multimillionaire long-term hermit globally fêted and squiring the likes of Isabella Rossellini since his thirties can offer relevant, hardearned wisdom and encouragement to folk dithering over sex with someone incapable of consent).

The narrative arts aren’t a lot of use, then, for the worst problems facing boulevardiers, mondains, exquisites. Nor are even the best concertos or pop music, to say nothing of sculpture and installations. You yourself know all this stuff, of course, but plenty of boulevardiers don’t.

Like everyone when they first go to recovery meetings, they have a God they worship and obey. That God is their own thoughts, the very addict’s thinking that brought them so low they have to attend these meetings alongside the grossly unhip. But most of these mondains have defined themselves at some point as unshiftable secularists. This is another way of saying that the one and only Almighty God they’ll ever allow themselves is whatever incandesces in their own mind. They are therefore more hesitant than many other recovery types about finding a higher power healthier than their addict’s thoughts. So they relapse again and again.

Each time is then justified by yet more addict’s thoughts. It was because their wife left them, because their wife returned. Because their football team lost, because they won. Because of Covid-19, because a vaccine was successful. It was because Ukraine was invaded, because of Gaza, Trump, LLMs, The Uninhabitable Earth, because the recycling bank’s too far away. It was because a Unionist’s dandruff dropped into their coffee. That last one’s mine, I’m afraid. Wrestling relapse, early October 2014.

‘Some bohemians,’ Les would say, ‘will actually turn up at their first-ever meeting after years of pandemonium and try to tell us how we should run our groups and lives. A good number of them are trustfunders too, meaning that following relapses they often get bailed out by their loaded parents. Meaning they’re never able to hit a rock bottom so scary it scares them into the humility needed to see that their very best thinking’s brought them to this low point of their lives. To see that they cannot solve this problem using the head which not only caused the problem but is the fucking problem.’

Meaning they struggle to remain sober long enough to become useful to others, the very thing that might overcome their egomania and therefore sort their head out. Others such as that fellow mondain who’s just swaggered into his first meeting sneering to hide the fact he’s utterly bewildered about drink or drugs or wrestling and recovery, e.g. believing its founder being a proctologist augurs AA poking around your bottom.

One of many ways you see life’s usual rules turned upside-down in recovery is attractive newcomers hitting on less attractive but long-term-sober members, who then spurn them as potential serenity-wreckers and relapse-catalysers due to their looks. The result is that knockouts who seek partners in recovery who’ll understand their addiction can sometimes be left at the mercy of those who value people for their looks alone. That frequently includes the mondains.

So-called 13th Stepping, more experienced and predominantly male addicts who hit on vulnerable newcomers and thereby jeopardise their recovery, which in GA/AA is viewed as seriously as rape, is particularly prevalent in groups dominated by mondains. This is because many mondains believe their tastes in documentaries and cuisine make them so special that suggestions like Don’t be a life-wrecking predator with newcomers never apply to them.

And to be fair, it’s also because those who attend hip meetings tend to be more attractive than the GA/AA average. If you walk into an unfamiliar meeting and find you’re surrounded by people with perfect teeth and adroitly strategised hair, you gird yourself for relapse stories, whines about jobs or partners or parents, whines about others’ shares, and wisecracks to impress the women, including those you make yourself. All of which seldom occurs if the people there look like the Uruk-hai.

Among newcomers who’ve been 13th Stepped, the mondains themselves, and anyone else infected by the refusal to change mindset or behaviour, the relapse rates at hip groups may eventually become lifethreatening. Other groups then have to knock some sense into these poor throbbers with oblique takes on smoothies and the Moog to stop them destroying the lives of newbies.

When told their God is their own thoughts the standard mondain response is to squint and blink. Then to give a bun-adjacent insane-thoughts-containing cranial area a Stan Laurel scratch and ask, ‘Well, what else is there?’

To which Les’s response is to grab his dog-lead, propose a walk round some local park, and say, ‘Let’s find out.’

Later he’ll suggest a blinkers-removing watch of the planet’s worst artwork.

The rear entrance to Santa Rita’s Psychiatric Hospital, Madrid

Sean Hannitys with Greying Waxed Moustaches: A Case Study

ONCE WE GOT OVER OUR SHOCK, we found our first watch of the series increasingly compelling. We had to find out how low it would go. Plus the fans’ and gatekeepers’ adoration of the thing was illuminating and engrossing, a compulsive-viewing trainwreck involving passengers cheering at another trainwreck.

Much about The Return is unique. Uniquely contemptuous, unique conditions that allowed it to get made and aired, unique measures needed to try to understand how bad it is, unique volume and seriousness of awful artistic choices. But these don’t just clinch the show’s status as uniquely bowfing. They confirm that we were meant to find it so. The bowfingness is too far-reaching to be explained just by a loss of ability from the supposed creators. The Return is systematically bowfing.

The viewers who completely missed the point, therefore, were trainwreck-passengers like César who posted online about their profound investment in the immersive, humanly relevant events they were watching. Who claimed that every last aspect of them is deliberate and that any deliberate choice is necessarily good, and told the sceptics we just weren’t smart enough to appreciate them.

By this stage our friendship was clearly done. He was refusing to reimburse me for thereturn.es, and we differed too much over the abomination. Like Trinna and Jorge we spied on each other on CCTV and indulged nasty thoughts about each other’s dejection. And in my case about César’s many bangles and wristbands and his bun and unbecoming moustache. These, let me tell you, don’t exactly make for an imposing look on a nightguard, no matter how scarred his face or how substantial his pecs and delts (see Part 7).

Unlike Trinna and Jorge we didn’t hide our spying. So what we recorded on CCTV at times was the other guard bent over his hut’s monitor to peer at footage of the other guard bent over to peer at his monitor’s footage of the other guard.

I also got footage of César Bartola, aged forty-two, as he browsed online for red leather wock‘n’wewl bumless chaps. I got footage of him as he munched through lettuces in one repulsive go. Or drank on duty, or smoked weed or meth. He’d no equivalent footage of me because I only had to sneak a tiny tab or pellet into my mouth. I also zoomed right in and got footage of his slumming-it-workwise-former-PhD’s face as it told itself what fun it was to re-watch some Return character we never see again take ages to wander up a corridor and then do nothing of interest whatsoever.

We got footage of each other as we typed out replies to the other’s comments on r/twinpeaks. Then as we replied to these replies when we got back to our separate huts after chasing and apprehending a phone thief. It’s hard to capture in words what it feels like to double-rugby-tackle a thief with a thief of a former pal as you figure out how to work lettuce-munching into your reply to his

Although Mr Lynch is certainly a Master, we should stop short of uncritically forcing a masochistic label onto our experience of S3. As usual we can detect a modular dissonance at play within the Master’s work which lets us sympathetically inhabit both the victim and torturer positions during viewing. The former position appears to become poetically actualized on-screen during the scene in which Jowday eats Sam and Tracey who have been awaiting her arrival in a large glass box which resembles the TV set of the home viewer.

Nonetheless, we should temper this uni-directional interpretation by noting how these two victims might represent not only those rightly enthralled by this magnum opus but also sourfaced, perma-envious, ageist, anti-auteur thugs like BurntheReturn in this thread who hate it. We now find ourselves switching from victim-like resistance and disgust at the actions of Jowday to the delight and satisfaction this amazing sadistic being must have experienced feasting on those philistine human brains.

There are certain patterns in fan defences of turkeys, and when frequently repeated together about a work they become a virtual admission of its rankness. Straw men, ad hominems and selective blindness are the defaults of fanboys served up a turkey—you’ll have seen this yourself frequently online, César, I told him one night at Santa Rita’s by walkie-talkie.

And this makes sense. If your starting point isn’t I’m neutral when it comes to The Boat That Rocked, so I’ll just see how it turns out, but Richard Curtis is a man-god, therefore this film is guaranteed to be geeenius, in debate you’ll have to keep resorting to dishonesty. You can’t admit publicly, or even to yourself, that the reason you admire this film is solely because Curtis made it, just as Mozheads can’t admit they admire his novella solely because Morrissey wrote it, and Mr Trump’s followers can’t admit that calling the invasion of Ukraine ‘genius’ and ‘wonderful’ isn’t out of order only because it was their hero who made the claims.

What do you do, then? You misrepresent what the haters have actually said. You muddy the waters. You have to, since if you don’t you’ll have to try to defend the indefensible.

An additional factor in this, one I didn’t bother to communicate to César, was that as I knew only too well from my own resentment of it, his resentment of my Season 3 loathing depended to a significant degree on repetition. As he went out on hospital patrols, typed up posts on reddit, Instagram, or thereturn.es, often flooded with his chemicals of choice, César would loop your words of loathing round his head. With each repetition his mind would make your words subtly more extreme—it needed these edits to avoid getting bored by all the repetition—till by the tenth loop he’d switched off his walkie-talkie and put your safety at risk if you were attacked. Yet the real problem wasn’t whatever comment you’d made. It was the galoot pondering it so compulsively and bitterly he couldn’t respond to it because his stoned bunned head had turned it into another comment entirely.

To be fair, I suppose Lynch and Morrissey and Trump, the three titans of cheesiness, don’t exactly make things easy for their followers, do they? Picture yourself defending the erasure of the erasure of the erasure, List of the Lost’s prose style, or Mr Trump’s disquisitions on E. Jean Carroll’s looks, and maintaining your integrity and self-respect. It can’t be done. Something has to give.

You could of course question your devotion to the great man, your defences of the indefensible, but that’s prevented by your brainwashing. And so you get churchgoing mothers who share memes celebrating the death of Biden’s wife and daughter in a carcrash. You get Morrissey fans who’ll weep at the thought of a frightened lamb, who threaten to send anthrax to those who laugh at his novella. You get Césars who’re basically good people, they believe, maybe a little moody due to the fact they contemplate existence in such depth, but still basically nice fellas, who tell the world their favourite moment in cinema is an infant-torturer’s comeuppance played for laughs, and put their colleague’s safety at risk because they’re in the huff.

Angela Nagle’s Kill All Normies dissects online transgression from both the right and left.

Those who claim that the new right-wing sensibility online today is just more of the same old right, undeserving of attention or differentiation, are wrong. Although it is constantly changing, in this important early stage of its appeal, its ability to assume the aesthetics of counterculture, transgression and nonconformity tells us many things about the nature of its appeal and about the liberal establishment it defines itself against. It has more in common with the 1968 left’s slogan ‘It is forbidden to forbid!’ than it does with anything most recognise as part of any traditionalist right. Instead of interpreting it as part of other right-wing movements, conservative or libertarian, I would argue that the style being channelled by the Pepe meme-posting trolls and online transgressives follows a tradition that can be traced from the eighteenth-century writings of the Marquis de Sade, surviving through to the nineteenth-century Parisian avant-garde, the Surrealists, the rebel rejection of feminised conformity of post-war America and then to what film critics called 1990s ‘male rampage films’ like American Psycho and Fight Club.

Then to this century’s most highly praised example of this tradition, and the series’ cult following. So yes, Mr Trump’s cult appear all the worse because they remind you of the series’ cult of transgression-cheering Césars. The reverse is also true. Some of us have even less patience with the Césars’ defences of the show because they so resemble the output of the other transgressive cults that have infected public discourse.

A non-bam looks at The Return or at a presidential candidate sneering at a rape victim’s looks and their response is You have to be joking. If you yourself are agnostic on Twin Peaks, I guarantee that if you watch as many clips of The Return as you can stomach, this will be your response. Guarantee it. Every single agnostic has this reaction: You have to be joking. This is one of the most lifeless, misanthropic shows I’ve ever seen, with maybe the worst characters and the worst acting.

There is practically no record anywhere of viewers not already fans of Twin Peaks or Mr Lynch, liking The Return or even getting through all eighteen episodes. Hardly anybody turned up on Twin Peaks discussion boards to say they stumbled across The Return, enjoyed it, and were keen to explore the rest of Twin Peaks and Lynch’s works. Which is why the series is enjoyed by so few young viewers. The only people willing to enter Season 3 subspace had, like my Curtis-hating colleague, been members of the cult for many years.

And the saddest thing about him, other than his judgement regarding drugs and clothes and hair and infant-slicers’ narrative arcs and the rest, was that I strongly identified with the guy. I of all people knew what it was like to be brainwashed, not least in the form of denial on various fronts.

When I was still boozing a friend’s sister gave me a copy of AA’s Big Book and I read it in a single go. For months I carried it around with me, including in the bars and clubs I stole people’s drinks in. I compulsively re-read its portrayals of denial and nodded and smiled along drunkenly at its wisdom and warmth. I stuck it under the noses of fellow drunks who seemed as though they needed a bit of wisdom to puncture their alcoholic denial. These were sometimes the very drunks whose beers or nips I’d just slyly stolen and who needed some warmth to cheer them up.

Yet not once did I myself consider going to an AA meeting. I was a prime example of the adage in that same book that when it comes to addiction, data-gathering and understanding are useless if not combined with action. Trust me, I’ve had more than my share of denial. You’ll later see more the night César and me played crazy golf at Santa Rita’s and dropped ALD-52.

So I knew how tough it was for him to admit he was wrong, to reach that absolute defeat he’d been seeking without knowing it. Admitting defeat isn’t exactly encouraged in our culture, is it? Not admitting it in any direct manner anyway. That slumped-shouldered brutalised porny how-did-I-get-here submission to the billionaire parasite class and the sociopathy and depravity of its culture, so pervasive you can hardly see it—that’s fine. That’s precisely what’s demanded of you throughout your life, one long capitulation, deeply denied but also deeply felt, to the message of all parasite marketing and propaganda: Submit. But not the fully aware type where you just admit to the truth of a personal defect and that you’re screwed. There aren’t too many Blu-rays featuring that kind of plotline in our security team’s shared locker.

This helps persuade all of us, not excluding Revolutionary Communists, neo-Nazis, actual Nazis who worship Satan, and Greying Manbuns who dislike Richard Curtis, that we aren’t submissives—we’re still potential world-rescuers and world-transformers, dammit—so we’ll remain on our knees and allow the degradation to continue. It’s not easy to escape from a prison you can barely see.

This means it becomes even harder to consciously submit and accept that drink, drugs, porn or The Return have wrecked your mind and heart and there’s nothing you (alone) can do about it. Dig in, grit your teeth, try and try again, a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, creative visualisation, brisk runs at dawn, Antabuse, solemn promises that if you relapse you’ll skip around Atocha station with a megaphone praising al-Qaeda… all good stuff. What if you’ve given them your best shot, though, and you’re still relapsing? What if you’re too shy for the Atocha stunt, or too hungover, or too suicidal? Might it not be time to accept you’re never going to beat this problem using nothing but your addict’s thoughts? If not, then when might be the time? After five more years? Twenty?

Something else Les drilled into me is that late-stage denial is seldom complete, seldom total. It can’t tell a late-stage addict they’ve no problem whatsoever with drink, or with hookers or sudden grappling, because such lies are no longer believable. What it does instead, then, is downplay the seriousness of the problem. Rather than non-existent, the booze, hookers or grappling problem becomes No big deal.

And as with resentments, MAGA, Take Back Control, brainwashing of terrorists, the anti-independence Shock and Awe of September 2014, ATL and BTL hype about The Return, and any other marketing campaign that sells you lies—including the existence of the self, Ella would insist—the key to the con is repetition. You must keep telling yourself it’s no big deal, ideally with a subtly less serious tone each time, a 4channish tone perhaps, loosen up FFS. Which means that by the tenth repetition No big deal has become, consciously or not, One more time, then and you find you’re pissed on the brothel’s doorstep or surprising your colleague with a tilt-a-whirl arm drag.

Only in extreme cases such as the anorexic tweens I pass on hospital patrols (It doesn’t feel like I’m starving myself to death) is late-stage denial anything like total. Most of the time it’s only partial—though with regular urges to return all the way to total denial, a self-deceived mark once again when it comes to hookers or wrestling or screens or drink or whatever you’re having yourself. This is why absolute self-honesty is emphasised by every recovery sponsor: because its opposite is destroying you.

As I zoomed the cameras in on César there in his hut, tweaked or stoned or drunk in his manbun-tilted security cap, I used to pray on his behalf that someday his delusion about The Return might bring him to a rock bottom so bad, maybe even requiring admission to this hospital, that it would force his eyes open to the true hell of his existence. If he got lucky he might overhear himself saying it doesn’t feel like he’s lost his mind, or some other accidental slip. The facade of his denial might crack and he’d find himself in the rubble of rock bottom, and its possible moment of grace.

My old friend’s time in the rubble lay far in the future, however, not in a psychiatric ward but in an A&E. As with every admirer of the series the poor sod’s problem for now was he was still in the early stages of his insanity. He had no clue yet how lost he was and how badly he’d been conned.

Reworks material from David H. Fleming’s Unbecoming Cinema: Unsettling Encounters with Ethical Event Films.