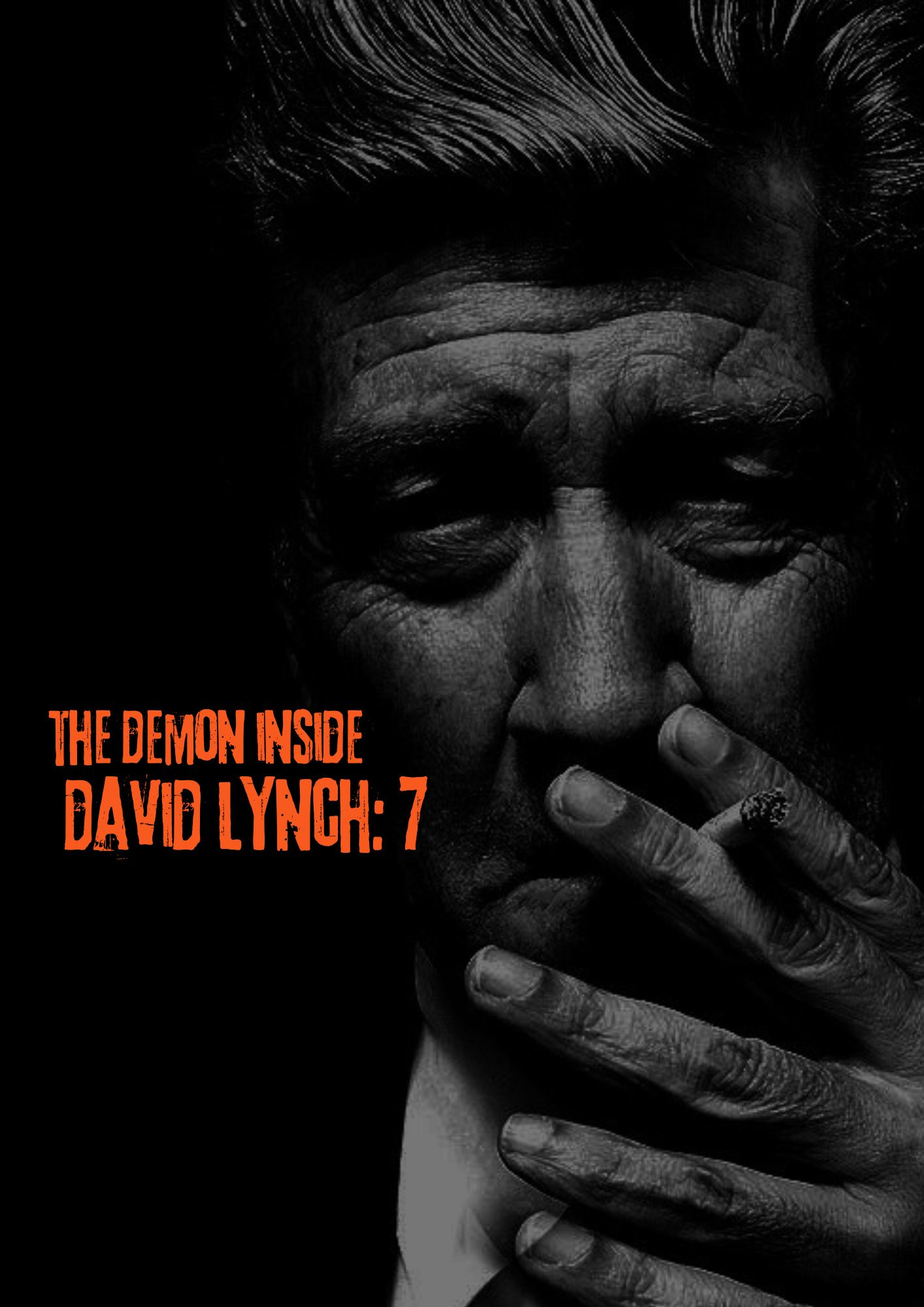

The Demon Inside David Lynch: TV Drama's Worst Fiasco 7

How Low Can You Go? ^ The Expressionist Looming Presence of The One ^ Idols and Voids ^ Are You Hungry? ^ But Who Is the Dreamer? ^ End of the Line

The Demon Inside David Lynch states that the celebrated director was possessed by a ten-dimensional entity that went on to make Twin Peaks: The Return. You won’t be surprised to hear this is fiction, satire.

Chapter 1 is here.

How Low Can You Go?

THINK OF THE LOWEST THINGS you’ve come across in art. Conceptions, decisions, moments. I don’t mean to boast, but I can beat the lot.

Within my top ten there is fierce competition for fourth place, the honour of being the fourth-worst element of The Return and therefore in artistic history. The characterisation, tediousness and pretentiousness, the worst ever seen and that we’ve barely looked at yet, all have a decent shout as they each take up a honkingness pie chunk of 4-5%. I’m reluctant to describe any work as pretentious, but as I hope is now evident, in the case of this series we really have no choice, even if like awful and unfunny the word in this context is nowhere near strong enough. Wait till we get to Part 10 and what the series does with T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets.

If as is sometimes said The Return is made up of both Season 3 itself and the audience reaction, then its marks’ reaction ATL and BTL makes up around 3.5%. The gulf between how funny it thinks it is and how funny it actually is would be a bit less than that. The retcon is perhaps around 2%. As for this retcon just being part of Richard’s dream, the erasure of the erasure, if you combine the two you’d be at roughly 4%. The ending as outlined by the Manage Mother’s Poison Explanation would be a little higher. Green Glove versus BOB I can’t put a percentage on. My head goes weird whenever I remember that one, so I really can’t think straight about it.

The writer-director-producer casting itself, or himself as we wrongly believed, as the masculine heart of every galaxy in the universe, all two trillion of them, makes up no more than 0.5%. If you’d cast yourself in such a role in your own dirtbag-swarmed TV drama your friends would give you funny looks, wouldn’t they, and start wondering if you think they’re vermin. Now picture their faces when they learn that of your drama’s honkingness this makes up a mere two-hundredth. What a work of art that must be!

Another strong contender for fourth place, the strongest according to Ella and Trinna, is simple to describe by the standards of The Return. Simple but not always easy, because when you try to type it out the anal clamps can be distracting: behind all its formal complexity and messing around, this low of lows appears to believe it constitutes a guide to living. A rallying cry of some kind, a moral and spiritual toolbox. Wake up! Fix your heart or die! it suggests to the people watching, many of whom it apparently views as clowns and scumbags. This as the showrunner peacocks about in the vainest self-casting of all time and puts his puerile spin on rape and disability and older or non-bombshell women.

By now we can see that The Return is indeed a wake-up call, from the ten entities. However, that’s not how the show presents itself. It presents itself as a rallying cry from a David Lynch who appears to believe he and his sub-sub-The Room mingathon have the authority to guide us towards a better life. Perhaps 5.5%?

A challenge for you. Say you’re watching The Room, Fateful Findings or Santa with Muscles and you sense the film views you and many of the people you know as worthy of ridicule or contempt. Now imagine that film combined with dozens more just as bad. The challenge: without your toes curling or your bottom clamping imagine this megamashup starts warning you to wake up in a spiritual sense. Wake up FFS, you Unterentwickelt Mensch! Santa with Muscles, the Potato Men, Larry Gigli, Bucky Larson, Bustopher Jones, Jack and Jill, Tommy Wiseau, Neil Breen, Catwoman, Howard the Duck and the rest of the gang are here to fix your heart with their spiritual toolbox in the form of the historic low that’s this very mashup! Hallelujah!

Can’t be done, can it? You can strain and grunt and will those toes downwards and that rim outwards all you want. But if you make a serious effort to imagine this mashup as an aspiring guide to better living then you’ve no chance. Best just to give in to the inevitable and let them curl and clamp.

Ridiculous, you think. Who’s going to take up a rallying cry from a film that awful? I agree, it is completely ridiculous. Yet this doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, and in response to something many times worse than that mashup. In the summer of 2017 Fix your heart or die! really did become the rallying cry of the poor kayfabed Manbams.

Back to that work you still believe might be worse than the abomination. Does it feature anything as bad as an attitudinal and behavioural wake-up call for human scum while the heart-fixing loner showrunner shares his fetishes regarding arousing rapists and the seldom-appreciated comedic potential of disabled people’s terror, and walks around self-cast as the core of the universe holding forth to his terribly acted pouty subordinate in a Federal Bureau of Investigations office on the sprightliness of his loner’s manhood, and its fans then rallying round that call?

NO → Glad to hear it. Forget that work and brace yourself for the remainder of the abomination.

YES → That seems unlikely. I’ve never heard about anything that bad in another work, or anywhere near. Assuming you’re telling the truth, though, does this make up a maximum of 5.5% of your candidate’s honkingness?

NO → See NO above.

YES → I think you’re maybe having us on. Since you refuse to play fair, there will be no more of these questions.

But not a single contender for fourth place is in the same league as the top three hideousnesses. For a start, the human mind can actually perceive the above contenders in full. They aren’t so vast in their effects and implications that you fail or refuse to even recognise them for what they are, for the demonic scale on which they operate. They don’t send people to A&E the way the rock bottom would do to Ella, Les, César and others. They don’t transform the manner in which waste is taken from your body the way it would to César and others. Or transform people’s love lives the way it would transform Ella’s and mine. They don’t get you official warnings from your bosses the way another of the big three would for César and me.

Their awfulness hits you in waves, yes, so that just as you’re recuperating from the last wave you’re suddenly blown away by your latest discovery or nightsweating realisation of how much you’ve underestimated some debacle’s hoachingness. But the big three are tsunamis that bury you deep within them then sweep you along in their wake for days, weeks, forever.

The funny thing is, you soon persuade yourself that the next time a tsunami hits you’ll be ready for it. Uncanny the human capacity for denial, it really is, because of course humans can never fortify themselves for horrors at the scale of these tsunamis. You’d be as well trying to head an asteroid back into space.

The second-worst element of the show, comprising around 12% of its awfulness, is something we’ve already covered. Can you tell what it is?

And how are you getting on with guessing the absolute rock bottom? I’m no expert in how to tease the nature of rock bottoms in artistic travesties, so I don’t know if my clues for this one are too heavy or too light. But keep in mind that a main theme in The Return is anti-nostalgia, anti-retro, that the series is based on the Orpheus myth, the Descent into Hell, and don’t look back. It’s based too on dozens more of our greatest myths and other narratives, all part of its heart-fixing toolbox, but the Orpheus myth, don’t look back and anti-nostalgia/retro are central.

As should be clear by now, it’s not just an attack on nostalgia, it’s a carpet-bombing. We can say without exaggeration that it’s the most anti-nostalgic work ever made. No cultist denied the attack on nostalgia. It’s a given of much discussion about the series and central to many theses and articles. Buzzfeed: ‘Twin Peaks Was The Ultimate Argument Against Nostalgia’; Vulture: ‘Twin Peaks: The Return Finale: Why It Defied Nostalgia; Popmatters: ‘How ‘Twin Peaks: the Return Resists Nostalgia’; and plenty more in a similar vein.

Or no cultist denied it, that is, until they saw the rock bottom. Then panicking at what the showrunner had wrought and what it meant for their cult devotion, they tried everything they could to pretend anti-nostalgia/retro isn’t central to the series. They had to. This is the headshot, far worse than anything else in the series, and the showrunner aimed and fired the gun itself. Even those of us who hate Season 3 felt sorry here for the greying Manbams, the poor sods.

If you have a TV drama that’s the most anti-nostalgic work ever made, then, what is the very worst thing you could run alongside this hostility to nostalgia? Of all the things that exist what’s the one you’d least want in your story? Because from start to finish The Return repeatedly features that thing.

An additional clue, as we’ve said, and one not unconnected to the above, is that the Twin was determined to make Mr Lynch look an ultimate galoot. Another of the ways it achieves this is through the series’ use of Eastern philosophy, and in particular the characters’ doubts that they’re who they think they are.

Ella went on about this too, of course, especially when trying to metaphorically slap me into lightening up. The self is just a language game, she’d say, a facsimile, a painting which we spend so much time on that we fail to see it’s just a painting. An imaginary friend we forget isn’t real and never has been.

‘It is at best a form of kayfabe 3 marking out in which smarts forget language is just appearance and not the reality, that it is literally a scripted game,’ she told me in June 2017 as we wheeled Chica through Retiro park in a Santa Rita’s wheelchair. ‘At worst it is kayfabe 1 in which we have not known for a single moment that we are marks.’

Later in bed she murmured ‘Kayfabe 2’ to let me know she’d faked her orgasm. As I was playing One Tough Young Hombre, however, and had her in a rear triangle grip as I brushed her with a feather duster, we both knew she was kayfabeing nobody. Anyway, you won’t be surprised to hear that Ella claimed the belief that you existed was more widespread and therefore invisible than any other kayfabe 1.

You are not your thoughts. God is not your thoughts. There are no non-circular justifications for the existence of the self; every form of suffering comes back to the concept of the self; forget it, then. Nobody’s ever escaped from a prison that isn’t real. There’s nobody home. Wake up from the most repetitive and therefore successful ad campaign there’s ever been, the purgatorial dream of your own identity. Not this, not that. Not me, not mine.

There are various koanish ways of talking about this, deliberately hard to pin down because pinned down they become mere concepts and what they point to is beyond any concept. But here goes in any case, at least as I eventually came to sense it as intended by the entities, and maybe craftily, even wittily, by their TV drama too (see Parts 9 and 10): there’s no such thing as Andy, as Ella or Les or Trinna, as Chica or Stanley, as César or Frank Boulègue, Club Gevurah jointly or separately, or even as the Twin or the other entities. All there is is the fucking isness awareness being presence blah void hee-haw nada within which these apparent facets shine, reflecting and absorbing all the rest eternally. In a very real sense, we’re all of us Club Gevurah, even hapless Michael Gove.

Now think about the Twin self-cast as Gordon Cole/Gevurah/Thoth, a saviour-saint-shaman-stud-superman in a world with human swine ahoy in all directions. Who’s listed in the credits as playing Cole? David Lynch is.

People were therefore left to conclude that this twice-daily Transcendental Meditator had cast himself as the centre of the universe in a story in which Transcendental Meditation-type ego-deflation and the questionable nature of the self are fundamental. That we were getting this, or so we believed, from a man who flaunts his immersion in Eastern philosophy induces an unusual feeling, not merely due to the vanity on display but the hypocrisy. ‘It’s like your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating’, in the words of Tibor Fischer about Martin Amis. If, that is, the masturbation was to photos of the uncle himself and he’d spent decades giving TED Talks warning about loners who skulk around playgrounds.

Meanwhile the actual loner Mr Lynch was unable to do anything to clear his name. He was stuck there inside his body watching this desecration of his beloved show and characters by a creature that everybody thought was him. He’d the ultimate front-row seat as he was made to look the sorriest diddy this planet’s ever produced.

Some empathy is surely called for here. Imagine that was you trapped within your own body as a ten-dimensional entity used it to make the most excruciating artistic effort of the last 300,000 years and then slapped your name on that effort. Imagine how that must feel, the disbelief to begin with, followed by the realisation that this isn’t a dream or hallucination. It’s definitely happening on the filmsets and then every week on televisions across the world. Feel the frustration and embarrassment as you watch the demon juxtapose the series’ vanity for the ages with references to the ego-deflation of Eastern practice and the world’s other spiritual systems, then present the resulting shambles as a guide to better living—all with your name attached. You have to watch people who used to admire you frown and gawp at your series with similar disbelief. They’ve waited decades for this, this turkey to beat all turkeys, passed off as a spiritual toolbox.

This nightmare is happening to you, once known as the nicest hermit in Hollywood. And because the Demonic Twin of You controls your body you can’t howl out your mortification and despair. Or even just hang your head and sob, or throw yourself off an L.A. high-rise.

Then the Twin makes everyone think you said a certain former reality-TV star, one who’s plainly some kind of terminal point of spiritual bankruptcy, could go down as one of the greatest US presidents in history. That, in my opinion, is overplaying the role of heel. That’s hamming up the Big Bad far more than the entities’ script called for. I told the Twin so when we later merged.

The Expressionist Looming Presence of The One

ELLA BEGAN TO VOICE MORE CONCERN THAN USUAL about my state of mind. She tried without success to dissuade me from making hatred for The One my new higher power. She refused to hear out any more critiques. Citing gynecological issues, she would no longer join me in rewatches. For a while she’d allowed the series to flavour our grapples, roleplaying Chrysta Bell pratfalling in her Tammy Preston high heels, or okaying three-ways with Chica as Tammy and me as the halfwit Deputy Andy Brennan. All of that now stopped, never to return.

Our grapples were also deteriorating in other ways. I was often so distracted by the series I couldn’t concentrate on the maintenance of our delicate bedroom balances. My fearsome wrestler act was suffering because it was hard to get provoked by the boggingness of any fact of life apart from The One. By now the show hadn’t just colonised the entire category of Artistic Disaster in my mind but also, it sometimes seemed, the categories of what was Unbearable, Disappointing, or even just Mediocre in Life in General.

Ella would try to provoke me into verbal grappling moves with whines about my drug intake, about my days missed at work, my general melancolía, and ignoring my GA/AA sponsees due to my fixation with the series—a betrayal far worse, she shouted, than I’d suffered at the hands of David Lynch. But my attempt to think of an erotically charged retort on the subject of her boggingness would get blocked by the Expressionist looming presence of The One in my mind’s boggingness zone. The best I’d manage would be some measly effort regarding her acting skills in bed being even worse than Chica’s or Bell’s, which might lead on to equally unerotic conjecture as to why the hermit chose Bell for this humiliation.

For a while I did spend more time with my sponsees and felt the better for it. In time they drifted away, viewing my Powerpoint piechart seminars as insufficiently germane to the potentially life-wrecking matter of their nondrinking or nonviolence. The only sponsee who stuck with me was Trinna, on the condition that each hour spent on the trainwreck’s horrors would mean two on the Ashkenazi Jews.

She was still so messed up at the time, and resentful of my hypocritical tip that she find a higher power better than her compulsive thinking, that to spite me she declared The One her higher power. Then she loomed Expressionistically over me trying but failing, just, to provoke a grappling relapse.

One night at Strobes + Robes things with Ella came to a head. Melancolía-free and talkative on a perfect blend of AL-LAD and 4-AcO-MET, I was informing the barstaff that The Return was worse than ISIS execution videos, which I sometimes claimed when high. What brought matters to a head, and to a headlock, was when Ella’s forty-eight-year-old ex Mateo Rodríguez strode up in a salt and pepper manbun and French-fork beard, plus a kaftan and cropped drainpipes. The series, he announced, might have been too deep and complex for me.

The kick drums were loud and Mateo’s struggles to free his head distracting, so I can’t remember the full content of Ella’s lecture that night. A point that did stick was I was at my most destructive and at times my most hateful when, as with The Return, I was in the right.

Another was that every obsession is in the end a self-obsession. When I obsessed over her in the difficult times we’ll come to soon, for instance, the looped thoughts weren’t about Ella and Strobes + Robes or Ella and her recovery from cancer. They were about how she related to me and me only. And the same was maybe true of my obsession with you-know-what.

It was now ultimatum time from Ella: get over that obsession or risk losing her. I watched Laura’s strobelit teeth and tongue as they shaped these words. Laura’s lip as it curled up at the corner.

This was obviously an unreasonable demand and I told her so.

Madrid’s Institución Nacional Lynch

Idols and Voids

ONE NIGHT IN JULY when Ella went to bed early I found down the side of my couch her unlocked phone. Some urge, some kind of vertical insertion, told me to have another look through her YouTube suggestions. To begin with they were mainly videos of singer-songwriters at their most plaintively annoying. Soon every video featured Madrid’s Institución Nacional Lynch.

One was a short documentary called Idols and Voids (Ídolos y vacíos) that outlined parallels between the aggression of Return fandom and that of the resurgent hard right. It began with the Institución’s video Who Are We? To the tune of the Who’s ‘Who Are You?’ and self-accompanied on electric guitar, the institution’s director, a film critic for El Mundo, sang in English to rows of seated mondains wearing drainpipes and greying, grey or white manbuns

I ain’t talking bout your name

Or no bluejeans or hairstyle, brother.

Jeans and hair are real interestin,

But I’m talkin bout somethin other.

We ain’t rumblin for no Emmys,

We ain’t rumblin for no King of Spain,

We ain’t even rumblin for no Master.

We’re rumblin to become real meyyn.

The director of the Institución Nacional Lynch was Ella’s ex Mateo.

His lyrics kept repeating the words ‘deep’, ‘interestin’ and ‘manly’ to reassure his fellow Manbams that their ideology wasn’t shallow, banal or submissive. David Lynch, The Return and its fandom were ‘Heavy, too heavy for some,’ he sang, ‘Too, too deep manly growls,/ A heavy workout among brothers then/ Manly haunches flicked by towels.’ As his performance continued, Polish rightwingers subtitled in splitscreen claimed the unembarrassed and unembarrassing fascination of European manhood.

After less than fullthroated chants of ‘Who who’ from his audience, Mateo continued huskily over footage of Voxhead violence against Catalunyans:

What makes Season 3 worth rumblin for

And worthy of the Master’s name

Comes from an avant-garde morality

Free of unmanly guilt and shame.

So now, NOW’s the hour for rumblin,

Them doubters must know grief and pain.

Them philistines are weak sisters, brothers,

And no sister ain’t no mayyn.

Whooo are we?

Etc.

Following this performance the documentary showed an interview with Emiliano, a latch-key kid who was smoking a joint behind his home in Ruzafa in Valencia when he first met a middle-aged Return enthusiast.

To begin with I thought the series was among the worst I’d seen, and was certainly the unfunniest. But the more I hung out with older men watching and rewatching it, the better I began to feel, about myself, about these guys who’d welcomed me into their tight-knit group, about my new approach to hair, about the world in general, even about the series itself. Even the unfunniness.

A Vodafone technician named Alfonso said he was recruited into the Institución Nacional Lynch as a bully without any sense of identity.

Outside my bedroom window Mateo [Rodríguez] would serenade me. His lyrics claimed that all this anger I had inside me, all this hate, was because I was a warrior destined since birth to join the struggle against those trying to diminish the Master. Ours was a majestic, noble cause, he crooned. If we failed, if The Return didn’t top the decade-end best-of lists, the culture of the straight Caucasian male with ambitious hair might be wiped out.

Alfonso used the term void for what he was escaping with his fandom.

When I used that word with other fans, saying how scared I was to confront the void of my existence, they threw arms around my shoulders and said they understood precisely how I felt.

When I joined them for our next group rewatch gig, Mateo was singing that the Master forces you to confront the void during those many long scenes with nothing happening, and then to confront the void again, and perhaps even tame it, when discussing or singing about the series with fellow connoisseurs.

Now it was my turn to nod along, until it dawned on me that a bunch of middle-aged men in skinny jeans in a treehut all screeching with delight as Mateo smashes his guitar and roars that watching and discussing and singing about silent car journeys forces us to confront the void is not the same as actually confronting the void. It’s just filling up the void with screeches, roars and a shattering Stratocaster.

These and other ex-fans gave reasons why in the end they’d had to leave the world of Return fandom:

Weariness and depression due to a lifestyle of habitual contempt, ridicule, groupthink, doublethink, cognitive dissonance, and age-inappropriate hair, clothes and meeting-places.

Being sectioned in a psychiatric ward.

Anger at the hypocrisy of group leaders. Some of these, it turned out, had stopped watching the series after the first few hours or even minutes.

Outreach from Return-battling groups such as the Antifa offshoot AntiRe, or No Return to The Return, an international organisation that helps former fans recover and in turn help fellow recoverers.

A sense of protectiveness regarding their newborn baby, and a resultant desire to bring it up in a world where it would never have to endure an ordeal like that series.

Mateo’s oeuvre.

The documentary ended with a plea from the rapper Pedro Habsburg.

As Season 3 fandom becomes increasingly normalised in modern life, and as these fans’ tactics receive increasing sanction from the mainstream media, the dangers of being socially ostracised recede. Therefore instead of ridiculing these men, showing them forgiveness and tenderness may better help them leave their fandom behind.

This does not mean, however, that it is safe for Season 3 resisters to interact directly with the likes of Mateo Rodríguez. Any offer of help needs to be presented with care and delicacy and outwith guitar-swinging range. Fans of the show are not only poor souls yearning for significance to fill their empty lives. They’re also a highly aggressive movement that seeks cultural domination, and that has enthusiastic backing in high places.

It was Mateo who’d got Ella into the Lynchian roleplay. Plus all her other roles. It was obvious. He’d had sex with her as Frank Booth, Ben Horne, Dr Jacoby, Sailor, and the rest. And she was so into it she got me to do the same.

Night after night we’d watched and ridiculed The One before going off to bed. Without knowing it, and gynecology permitting, I’d then roleplayed this French-fork-bearded singer-songwriter and director and unbelievable balloon of the Institución Nacional Lynch.

Are You Hungry?

BEFORE WE EXPLORE the third-worst element of The Return and of art generally, we should remember the masterpiece whose events are wiped out, made completely meaningless, by the erasure of the erasure and the erasure of the erasure of the erasure.

Fire Walk with Me had a greater impact on me than Twin Peaks the series ever did. The original show has several moments that in 1990 were genuinely revolutionary for TV drama, but few episodes as a whole have aged well. Yet despite being slammed on its release by the critical gatekeepers, Fire Walk with Me is still for me an obvious masterwork, transcendently and shatteringly beautiful as the best of Resnais or Tarkovsky. A number of people I know who were raped as children, and in ways and circumstances as bad or worse than mine or Dougal’s, found real consolation in this film’s compassionate treatment of Laura’s torment.

Whether you’ve been abused or not, its most harrowing moments are the climax when BOB bludgeons Laura to death, and the sex sequence in which she finally learns that BOB’s a demon that’s possessed her father Leland. An earlier scene at their home’s dining room table is also highly disturbing. Laura sits down across from her father, who she now suspects might be BOB. Fatherly cardigan on him, and an incestuous rapist’s smirk and twinkly eyes. Then in one of the most sinister moments in cinema he cheerfully asks his daughter: ‘Are you hungry?’

Here at last Dougal and I found ourselves watching something that seemed to care enough about victims of incestuous rape, made by someone who’d really imagined himself into the dismal texture and feel of such a life, to portray not just the obvious drama of the rape itself but also the everyday actuality of sharing hearth and home with your rapist. What it’s like to sit daily across a table from someone who for years has forced himself inside you before splashing his fatherly semen across your buttocks, back or face.

Which is why we came to cherish this film and director. And it’s why when the time came to choose a higher power, something or someone I could unquestioningly look up to and who wouldn’t want me to relapse, I chose David Lynch. Whenever I handed a relapse decision over to the Lynch of Fire Walk with Me, to what that film said he stood for, I never drank or wrestled.

David Lynch didn’t save my life, Dougal’s life, or that of anybody else I know. But he did make one of the most humane and gracious films I have seen.

Yet some cranks go on insisting that the same man made The Return.

My pecs and delts. Photo by Ella.

But Who Is the Dreamer?

COMPRISING AROUND 10% of the series’ honkingness and responsible for foreheads banged in freaked disbelief off furniture, if not for trips to A&E, the third-worst element of the abomination is what’s revealed by Kreider’s essay ‘But Who Is the Dreamer?’ and the erasure of the erasure of the erasure. As you’ll know if you’ve read it, this piece is persuasively argued, though in my case its true significance only revealed itself over time, gradually and then suddenly.

It’s also one of the very few analyses I’ve seen attempt a comprehensive understanding of Season 3. Many of the rest have titles like ‘ “If Jupiter and Saturn Meet”: Astrological Dualities and Time in Twin Peaks’ or ‘Lucy Finally Understands How Cellphones Work: Ambiguous Digital Technologies in Twin Peaks: The Return and Its Fan Communities’. Ask almost any cultist for an explanation of the series as a whole, or even an attempt at one, and they’ll just shrug, then moments later will be back proclaiming the series’ magnificence; Jim Jarmusch: ‘That is a real work of incredible beauty because it is so incomprehensible.’

And as with masterofsopranos’ famous explanation of The Sopranos’ ending, Kreider’s piece makes sense of thousands of elements that without it would be left pointlessly hanging. Kreider makes sense too of the sick and kooky touches, all of them, and of the sickness and kookiness themselves. He shows that each instance is just a fragment of a dream or hallucination.

You might not like this, and neither do I, and as we’ll see neither does Kreider himself. Then again, we’re in beggars/choosers territory. His is the only proposal I’ve read that doesn’t take the show’s zaniness at face value and refuse to acknowledge its unlikelihood and extremity. It’s a question the cultists never get around to asking: Why this kooky, even by the standards of David Lynch?

Apart from Kreider’s the most praised analysis of the series as a whole is Martha P. Nochimson’s chapter ‘The Return of David Lynch’ in her Television Rewired. Like most of Nochimson’s work this chapter is stylishly written, but it has the same kayfabe 1 failings as nearly every other piece that lauds the series, failings that Kreider avoids because he’s prepared if necessary to knock the artist in question. The first failing is the usual one, the refusal to even mention the defects everyone not a Grand Maître cultist baulks at. To see what the second is we need to go back to critical basics.

Artist-centred criticism has three tasks.

1. Say what the artist is setting out to achieve.

2. Discuss the merits of this aim.

3. Say how well they achieve it.

This is both common sense and long-established practice. In the current study of The Return we have

1. Make the vilest work of art in earthly history, an atrocity that reflects back to humans what we’ve become and come to value. Hopefully this would slap us out of the most harmful of our denials.

2. Fair play.

3. Supernaturally well from a formal perspective. The Twin underestimated our tolerance for extreme trash, though, and how brutalised and defeated we are in general, and so had to try again with Season 4.

One problem with academic criticism is that the second task’s frequently ignored. Here’s Nochimson on The Return.

1. To communicate Lynch’s opinions and speculations on quantum physics and on time viewed as a Möbius strip.

2. No comment.

3. ‘Perhaps it is the mantle of James Joyce, William Faulkner, and, even more to the point, Franz Kafka that now belongs to Lynch for his transformation of American television into a medium that can provide both the humanising influence of modern art and its mind-expanding visions.’

When it comes to how worthwhile quantum physics and temporal Möbius strips are as core subject matter of a television drama that revolves around rape and other sexual abuse, she says nothing. We can debate whether they are in fact central, but Nochimson believes they are. Yet not once does she question this project’s worth. The reason is the same as for every cultist critic: because she believes that anything the great man attempts is deserving of praise since he’s a virtually infallible genius.

Nochimson’s one of the few who’ve even tried to say what the series as a whole is about. Meaning that out of the three essential tasks of the evaluator, what most of the series’ fans, pros or otherwise, give us is

1. No comment.

2. No comment.

3. Work of genius.

This is kayfabe 1 criticism, kayfabe 1 groupthink. The Manbams’ blindness to, or refusal to engage with questions of thematic value is one more way they demean themselves and attract mockery as brainwashed Nathan Barleys.

Part of Kreider’s argument proposes that everything leading up to his appearance actually being Richard’s dream is itself just the dream or hallucination of another man. He acknowledges that this person may or may not resemble the FBI agent Dale Cooper, or the finale’s Richard: ‘ “Richard” may still not be the “real” Cooper we saw superimposed over the leave-taking in the Sheriff’s office, but he is, at least, one layer of reality closer to the dreamer inside whose mind the drama of Twin Peaks has unfolded.’

Unlike almost every cultist critic or researcher, this evaluator is honest enough, free enough of indoctrination, to admit he’s not at all keen on what he’s discovered, i.e. he pays attention to task 2.: ‘I think the reason it hasn’t occurred to more viewers isn’t because it’s particularly implausible or obscure, but because it’s so unwelcome. I don’t like this interpretation any more than you do: in fact I hate it. It threatens to render all the characters and their dramas in which we’ve become so invested moot, mere illusions.’

It’s not often a commentator fully explains a celebrated work then admits they hate that explanation. Even so, Kreider underestimates how bad it makes The Return. I did too.

He believes that as with every Lynch drama from Lost Highway onwards, the series’ core theme is denial, a theme it of course shares with the present study.

For the last twenty years David Lynch has been making different iterations of the same story: someone isn’t who he thinks he is. Each of his films in this period tells two stories, one masking the other: the one the protagonists are telling themselves, and one they’re trying not to. The surface story is always a clichéd genre fiction (noir, melodrama, ingénue-goes-to-Hollywood) in which they star as victim or investigator, innocent and heroic; but in the true story, the one they’ve repressed, they’re the villains, guilty of horrible crimes they’ve tried to forget…

Cooper/Dougie and Mr. C. are in reality two halves of the same personality: one an idealised self, the other repressed. The entire story of The Return can be read as a battle between good and evil not in the Pacific Northwest woods, but in one man’s soul. In an audacious (or appalling) final stroke that completes (or forever defaces) what may well be his last major work, David Lynch intimates that all the inhabitants of Twin Peaks and their dramas, and its Byzantine mythos of demons, giants, and the Black Lodge, are an elaborate fantasy, the dream of this original Dale Cooper—or whatever his real name is—a desperate attempt to forget what he knows, on some level, is the true story.

Kreider’s next sentence is important for his theory’s contribution to the piechart: ‘What that story really is, we can’t know for sure.’ Due to this underlying story’s vagueness and obscurity, all we know is some offscreen man somewhere feels guilty about something or other that happened offscreen involving some mystery woman. This is the actual story behind the entire series. More than anything, it’s the comprehensive nature of Kreider’s theory that ends up making people headbutt furniture and run babbling into traffic, and gets security guards official warnings.

Remember that we’re already starting from an extremely low point, the historic mince of the erasure of the erasure of the erasure. But as usual it gets worse with this abomination, much worse the deeper you go. What Kreider proposes is that all the erasure of the erasure of the erasure has been communicating over every minute of the show’s 1000 is one proposition and nothing else. One vague idea about some guy’s guilt again and again and nothing else. If he’s right, therefore, this is among the mingingest artistic decisions ever made. Unless you’ve had very bad luck, it’s worse than anything you yourself have previously come across.

We aren’t finished yet, because the full repercussions of his theory are even worse. You may already see what they are. If not, you might want to apply some muscle relaxant.

You never forget where you were when that nagging feeling finally ended and you understood what ‘But Who Is the Dreamer?’ really means for Season 3. César and I’s memories go back to a full-moon Tuesday night in Santa Rita’s TV room when we were attempting to break up a relatively heavy food-fight. (When I started at the hospital I was warned full-moon nights would be eventful but didn’t believe it, but I was wrong).

It turned out the food-fight wasn’t due only to the moon. It was also due to the transgressive disc slipped by a certain moustachioed guard between the covers of Harry Potter y el misterio del príncipe. This kicked off mayhem when the patients found themselves watching Johnny Horne’s contorted agonised face, panicked wheezes, the futile panicked kicks of his tied-up legs, in a three-minute scene played as comedy. It was in our house now.

Security guards aren’t allowed to touch patients at any time in Santa Rita’s. To break up fights you have to get in between the antagonists and windmill your arms fast at your sides and hope this stops the antagonists launching themselves at each other. I’m serious. A couple of times per shift, roughly ten times a week, five hundred times a year, you find yourself between furious patients, and windmilling away till you provoke laughs so hard the patients lose interest in violence. It’s a humiliating but effective approach that also really builds your pecs and delts.

There César and I stood with our impressive chests and shoulders, windmilling at top speed as we debated The Return’s therapeutic value for psychiatric patients. I offered as evidence the latest face mashed into a tarta de Santiago. César answered that food-fights were a healing ritual in many ancient cultures.

Some unknown bloke feels guilty looped through my head as I then tried to dissuade patients from escalating to outright violence. It’s possible they weren’t the only ones affected by the moon. Maybe full moons open up your synapses in some way that lets you comprehend everything more deeply, especially if you’re already on 4-HO-MiPT. Whatever the explanation, that’s where I was when the full reverberations of Kreider’s essay went flooding through my nervous system.

My arms stopped windmilling and dropped to my sides. Calling past the food-fighters’ grunts and oofs, and splatted by the occasional daud of salted caramel, I filled César in on what Kreider’s essay really meant for The Return. His arms stopped windmilling and dropped to his sides.

The food-fighters could now clat one another with even more ice cream and tartas. We were later given an official warning over this but I shrugged it off. If I didn’t yet know the full scale of the show’s rankness, and never would, I at least had a better sense of how much Kreider’s theory added to the current honkingness pie, the honkingness tarta.

Say you have to explain to a class of teens how to get ideas across in narrative art like The Return. You’ve chosen this work because it’s the BEST TELEVISION SERIES EVER—it’s been written along the top of your whiteboard for weeks, that claim. In today’s lesson you tell the class that over its five-month initial run the show has one thing to say and one only, one message that gets drummed into the audience thousands of times.

Already there are rows of raised kids’ hands. You ignore them and summarise for the class the erasure, the erasure of the erasure, the erasure of the erasure of the erasure, then the various stages of the Manage Mother’s Poison Explanation.

Yet more raised hands and from the girls some Ews. A bratty boy holds his nose.

When the class has settled down you write on the left-hand side of your whiteboard the single revelation so profound, so urgent, it has to be repeated thousands of times:

Some unknown bloke feels guilty about something or other

Mutters circulate, and more Ews. There’s a Yikes and a Blech. You ask the class for suggestions as to how an artist might communicate the above message in a TV drama.

The raised hands are lowered. Silence. Your students are embarrassed by the Manage Mother’s Poison Explanation and by the less than profound and urgent revelation you’ve just written up.

So after drawing the moment out, letting the expectancy build—slouching like Julian Casablancas used to when he was half the age you are now, with one hi-top’s sole placed against the classroom wall, moodily, charismatically, hauntingly teasing the kids about whether you’ll even bother answering your own question—on the other side of your board you write

WAY TO COMMUNICATE THIS MESSAGE: Diane goes ahead and smashes the OG who raped her. Big yikes for sure, but she gets hella turned-on by it. Plus it’s even more Gucci than that, because with this smash she’s tryna possibly summon across dimensions that rumoured unGucci entity Jowday, yeah?

All this contains two dank allusions to James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake, one to the ancient Chinese divination manual the I Ching, and one to Kalki, who in Hindu mythology is the tenth avatar of Vishnu, yeah fam? Can I get an amen?

You don’t get any amen. What you get is bedlam. Giddy teen laughter, desks banged by several foreheads. Nobody, but nobody, is falling for this as the BEST TELEVISION SERIES EVER. Their bumholes are clamping hard and so is yours.

The class probably thought the Sex Magick! couldn’t get much worse, right? Wrong, kids, wrong. It is always wrong to assume you’ve hit the lowest point of any aspect of this catastrophe. Always. There are always new depths to sink to, new debacles to shock your hole into action. Beneath Diane’s voluntary sex with her life-wrecking rapist Mr C, itself one of the most godawful things to feature in a TV drama, lies the silly attempt to latch onto Finnegans Wake. Beneath this lies the erasure of the erasure of the erasure, itself one of the worst things in the history of art. Beneath this lies the fact that the sex and allusion and erasure of the erasure of the erasure and everything else in the best television series ever are meant to convey over and over, time after time for almost twenty hours the barely-even-trivial notion that some unknown bloke somewhere feels guilty about some act or thought or whatever.

Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr. are opaque enough but they wouldn’t deserve such ridicule from the class. In those two works there’s sufficient correspondence between the ideas being communicated about denial and guilt and the forms chosen to do so. Sufficient correspondence is the heart of communication. This is obvious, to everyone but César and the one-man house band and roleplay king and the other Manbams, it appears. So if only for their sake we need to explain it.

If you’re a lawyer trying in court to prove your client Suds’ innocence of child-rape, say, this is the message you wish to communicate to the jury. The form you choose to communicate this message is your evidence, e.g. Suds’ wife’s statement that he’s never laid a hand on his own kids. What you don’t do is provide as evidence footage of your client’s arousing intercourse with his own rapist Mr C to beckon across dimensions a rumoured being to perhaps be destroyed by Scream/Electricity Magick!, and that all this contains references, just about, to Finnegans Wake, the I Ching, and the tenth avatar of Vishnu.

Do you know why this wouldn’t be very impressive evidence? Every kid in the class would know. It’s because there’s not enough correspondence between your client’s supposed innocence of child-rape and his arousing intercourse, etc. Not enough correlation. The arousing intercourse and references are… irrelevant. As expression on your part this might be viewed by some people as shockingly so-bad-it’s-good behaviour in a court of law, and would likely gain you a fanclub of Césars guffawing at the way you desecrated a child-rape trial. But not as communication, not if you want your client to go free, that is to get your message across.

In the same way, a writer-director-producer-star-hermit who expresses his emotions and fetishes alone in a strobelit clearing in the woods, his body smeared with mud, quiff topped with a crown of wildflowers while he jitterbugs with squirrels and throws nutshells at sycamores for months to remind himself and his flowers and furry buddies that some bloke somewhere feels guilty, all this might be viewed as okayish conduct for a hermit. If we stumbled across it hopefully we’d be open-minded enough to see it as an interesting case of self-expression. The hermit’s damaging no one, he’s keeping himself fit, creative, entertained, and sociable, more or less—sure, fire away, Mr Lynch. Not so okay, however, if he puts up billboards around the world that point towards the clearing and announce Twin Peaks: It’s Back After Decades Away, Folks. Roll Right Up.

Bear in mind the all-encompassing and simple nature of Kreider’s highly persuasive theory. Some unknown guy feels guilty about some unknown act: drummed into the viewer again and again, this is the beginning and end of what’s really happening in the abomination. Which means that every single aspect of the series communicates that and nothing more.

Here’s a Whatsapp message I once received from César at Santa Rita’s.

S3 is an unashamed champion of boredom and offense and elevates these feelings to a productive form of critical refusal, a method of rejecting pleasure and taste in order to awaken viewers to a new life, even a New Jerusalem.

This heroically brave masterwork expresses symptomalogical enervation with the practices of mainstream media consumption, with Mr Lynch harnessing boredom and disgust as an artistic impetus and a subversive political mode of critique which transgressively invert the dominant coding system to bore and offend everyone to tears of delirious joy.

At what point, would you say, do people who type out this kind of thing become a psychiatric worry? How many communiqués like this must they send before you have to visit their hut, remove the spliff from their lips, and tell them that these elements of the show they’re so concerned with sharing, if their guesses are accurate, are awful art, miserably rotten, and grooving on them appears to have made them a candidate for admission to this hospital?

Now wipe away what you just wrote on the whiteboard about the Sex Magick! communicating some offscreen guy’s guilt. And replace it with César’s Whatsapp, see how the class reacts.

WAY TO COMMUNICATE THIS MESSAGE: S3 is an unashamed champion of boredom and offense and elevates these feelings to a…

They’re gone, these kids. The laughter and butted desks can be heard throughout the school. These aspects of the series you’ve been writing up are bowfing enough anyway, but as ways of communicating this preposterously obscure and irrelevant idea regarding some unknown man they become almost literally abysmal. When they contemplate them the kids feel on the verge of twirling off into outer space, emptiness, utter blackness.

They’re never going to forget this day. You’ve taken them close to the limits of artistic garbage. Decades from now, huddled in some basement shelter as the world falls apart above them, some of these kids will still be wincing about today’s class.

Even if by some fluke you manage to turn the lesson around and explain these aspects as a valid way to communicate some offscreen man’s guilt, you just know that within one of those uppity teen minds lies the real question you’ve been dreading: Why would anybody do this? Why would anybody make a drama on the topic of some unknown man’s unknown misdeed and communicate this via month after month of trash like the Sex Magick! and all the other offensiveness and deliberate boredom?

Rampant cheesiness, is the answer. Cheese down to even the obscurest mirrorings. The insertion into nearly every technique at every level of 4channish so-bad-it’s-good-no-it’s-actually-minging.

Up shoot more hands: Why would anybody do this? Why would anybody in these warming-up-for-armageddon times film an eighteen-part drama that’s like 4chan? Why would anybody give them enormous amounts of money to do it? Why would anybody then call it THE BEST TELEVISION SERIES EVER? Isn’t 4chan for confused, frightened, antisocial boys our age? Ew. Blech. This ain’t it, chief.

The bell rings. The students leave the room shaking their heads in disbelief. They’re already sharing your teachings across social media.

An anorexic girl frowns back at you in concern as you remain stubbornly at the board. You wipe away César’s messages and try to figure out what else you could put on the right-hand side.

The Returnian’s 1124000727777607680000 potential combinations, maybe, each of them communicating nothing but some offscreen man’s guilt over some unknown act.

Or perhaps this from Matt Zoller Seitz in Vulture.

As Cooper talks to Teakettle Jeffries, a puff of steam emanating from the teakettle’s spout takes the shape of the Owl Cave rune… Its wings break off and float over the rune’s body, forming a figure eight, the same number glimpsed on the door of that very motel room, and it becomes an infinity symbol when turned on its side. It’s worth noting that ‘Part Eight’ of The Return happens to be the episode that links the first use of the atom bomb with the creation of BOB and Laura and the first terrestrial visitation of the skull-crushing Woodsmen.

And needless to say, this is just a fraction of a full list of every part of the series, every bit of zany ugly plodding shambolic spiritually overblown snobby chauvinistic epochally unfunny infantile irrelevant megalomaniacal plectology through almost 1000 minutes of pre-apocalyptic prestige drama intended to let us know merely that some mystery dude’s feeling at fault about Christ knows what.

Your mind flinches at such a possibility. Kreider must be wrong, it thinks. Must be. No work could be this bad.

But are you sure of that? Going by what you now know about Season 3, do you really want to write it off that easily?

We have to remember Kreider does provide a rationale for the likes of its ultimate kookiness. In the absence of such a rationale we might have to take stuff such as the cultists’ analyses of the Manage Mother’s Poison Explanation at face value. If we’d like to understand the show we might have to pay that sort of junk attention for whole minutes of our lives. Kreider at least lets us write it off as some unknown guy’s dream or hallucination. It’s toe-curling, and ankle-curling, and got us an official warning, but it’s still a rationale. Beggars/choosers.

One of the hardest things when it comes to getting my head around The Return is that I honestly am not up to the task intellectually. Whether it’s down to research chemicals or too many years of drink or nightwork or just to basic cognitive deficiency, I can’t stretch my mind anywhere near far enough to perceive the full panorama of the show’s anti-splendour. I can talk on the subject of honkingness pies all I want but the reality is if I attempt to get a true sense of the contents of this show’s pie, its full list of ingredients, my mind tends to duck the challenge and tells me to take drugs and stop thinking about The Return and warming up for armageddon and just watch some WrestleMania.

So there are times when I wonder if I’ve ranked the top three hideousnesses correctly. Do the implications of Kreider’s theory really only deserve third place? Or did my mind simply shrink from the challenge of perceiving the full scale of their hoachingness? But then you remember the rock bottom and how it later transformed this whole story, and remember the runner-up as well. Now you know for certain, or think you do, that nothing in the history of art, not even from this crime against humanity, could ever supplant them in the top two places.

Do we even need to rank them at all? My ex-sponsor Diego served fourteen months in Aranjuez prison for kicking his father-in-law into a three-month coma. First relapse in eleven years, fourteen months for a crime he has no memory of, because at the time he was in blackout. During AA meetings in the prison he called this his rock bottom. When he was released he went straight to the nearest bar. During a blackout he was later arrested. Turned out he’d swung a lamp at his mother’s face. He went on to serve eight months for this, and started calling it his rock bottom.

Going by the respective sentences handed out, the courts disagree. But when you keep hitting these kinds of lows, how can you tell for sure which is the lowest? Kreider’s theory is just a theory, whereas Season 3’s rock bottom and runner-up are definites. Diego missed his mother’s face with the lamp, whereas he didn’t miss the head he kicked unconscious. Then again, this head wasn’t on the woman who birthed him. Perhaps what mattered in his case was not which was the real rock bottom but that he kept offering up new candidates for that title. He hasn’t touched a drop of drink, mind you, since the prison screened an unusual eighteen-hour drama to force inmates to reconsider their lifechoices.

Now imagine you yourself were responsible for the implications of Kreider’s essay. You were the person who took a TV revival anticipated by fans for decades and then for almost half a year gave them nothing more than some mystery dude feeling guilty over some unknown act, and communicated this via ultra-obscure, pretentious or sick storylines and a ridiculous volume of tediousness, and thousands more instances of junk. You did this, not the hermit, not his Demonic Twin. You. This is the artist and person you’ve become.

And I only came across Kreider’s article by chance, following a mention in Laura’s Ghost. Which means there may be other articles out there, now or in the future, that reveal new aspects just as bad or worse. Remember this theory grew the already gargantuan pie considerably, which opens up the possibility that as more articles reveal more aspects the pie might grow and grow, perhaps forever. You wouldn’t put it past a demon operating in ten dimensions to bake a honking pie that never stops growing, would you? Might the Ultraverse be not a Diamond but an eternally baking, eternally ballooning Pie?

So those are the three worst hideousnesses (that we know of) of the worst artistic project of the last 300,000 years. They are the worst cruelties (that we know of) the Twin inflicted on Mr Lynch. Before you experience the top two in their full glory, though, you’ll need a proper introduction to this monstrosity’s central characters, and we’ll also look into the causes of other kinds of rock bottoms.

We may never comprehend the full scale of this series’ vileness, which could well be infinite. Nevertheless, if we continue on this journey through hell we should soon be gazing down upon the lowest points we know art has reached since homo sapiens overtook the Neanderthals.

End of the Line

WE WERE DISCUSSING Ella’s recent dinner with the French-fork-bearded minstrel. When I asked if she’d put him right about his favourite show, his trousers, hair, lyrics, gigs or his approach to life in general, or asked if his beard represented, from his perspective at least, twin mountaintops, twin peaks, she said the subjects hadn’t come up. When I asked if she ever missed sex with him she just blew Fortuna smoke at my face.

3-FEA shot round my blood and moments of our years together came to me in a burst. Skeletal sparrows chittered along the windowledge and the curtain’s web shimmered along the floor—we’d come out of a drug bender to find we were now engaged. We stopped to look at shop mannequins with mascara running down their cheeks and Ella’s face brushed mine as she released a bereft-sounding OOewOOeww. We wheeled Chica/Tammy through a Vox rally and got Santiago Abascal to shake her warmth-free hand.

As we approached her flat Ella seemed tired. She was often tired these days. We climbed the stairs, Ella ahead of me with her head bowed and shoulders curled.

We went inside and through to the bedroom. Faintly lime-green moonbeams shot through the window and across the floor. I watched Ella undress and said, ‘You look drained.’

‘I am drained. And I am drunk.’

‘You don’t feel sick?’

She stood before me naked. ‘I am just drained and drunk.’

I pulled her closer and said, ‘So what have you been thinking about?’ She resisted me a bit, pressing her hands into the tender muscles of my chest. I took hold of her hair and said, ‘Maybe Laura versus Frank Booth tonight.’

Crinkling her nose she said, ‘I was thinking that I have had enough of it.’

She pulled away and lay down on the bed. Her fake breast threw across the floor a cartoonish shadow.

‘Enough of what?’

‘What do you think?’

In the wardrobe mirror my face lost its sickening grin. The side of Ella’s head was reflected there as well. The blonde was faintly greened by the light outside.

She poured herself a brandy, drank some and said, ‘Frank and Laura is one of Mateo’s. But I am not Laura. I never have been.’

Taps at the window from green-tinted raindrops. Somebody somewhere was watching a comic turn thwaakk BOB.

‘And you’re going back to the minstrel. Or are back with him already, for more Laura and Frank. The roleplay, you got it from him. From an ancient singer-songwriter who wears trousers like that.’

Again I looked at the mirror, at her hair as it gleamed inside a shroud of green moonlight. Then at her shadow along the floors and walls, at her unfinished brandy.

‘Your own trousers are not always so great, chico.’

As it caught its reflection, my face in the mirror crumpled. ‘Slim fit.’

‘Qué?’

‘Slim fit, never skinny. Big difference. In a middle-aged guy it’s a different moral universe.’

‘Who cares. Really.’

‘So I’m being dumped for an old rocker who wears kaftans and a bifurcating beard. Who got you into the roleplay.’

‘He can be mucho… ’ she growled the word: ‘inventive.’ She finished off her brandy. ‘You should not be taking the drugs if you cannot cope with them.’

‘Bit late for that, isn’t it?’

‘You’re too unstable, too bitter.’ Quietly she added, ‘And too different on los fundamentos.’

Mascara trickled down her Laura cheeks. I took her glass and poured myself a brandy.

‘Poor Mateo, he can be so very tender. Please do not drink that.’

I inhaled fumes of Hennessy. ‘Tender before turning into Frank Booth.’

Panic now seized me, as though some old tormentor had crept up behind me. Or was lying there on the bed.

The glass of brandy flew through the air.

It smashed against the wall.

And that was the end of that.

Reworks material from Joan Braune’s ‘Void and Idol: A Critical Theory Analysis of the Neo-fascist “Alt-Right” ’.