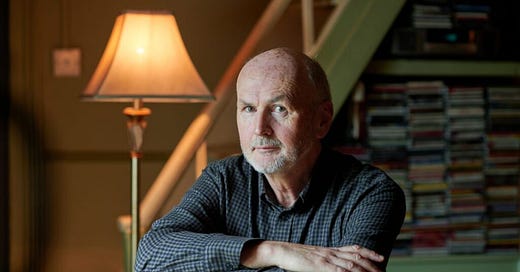

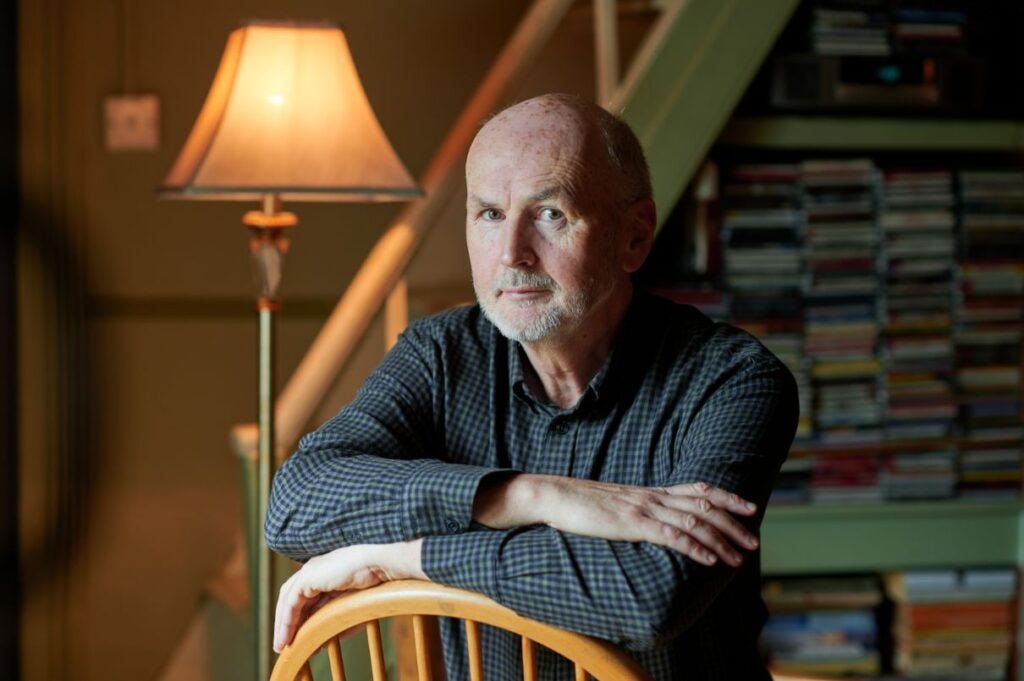

Born in Dublin in 1958 Niall Williams has been quietly prolific since the success of his first novel, Four Letters of Love, in 1997. His eighth book, History of the Rain, was long-listed for the Book…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Auraist: picking the best-written books to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.