The best-written British novel of the century (and hardly anyone's read it)

Plus the best-written SF/fantasy novel of the century

Photo by Dorothy Lin

In today’s issue:

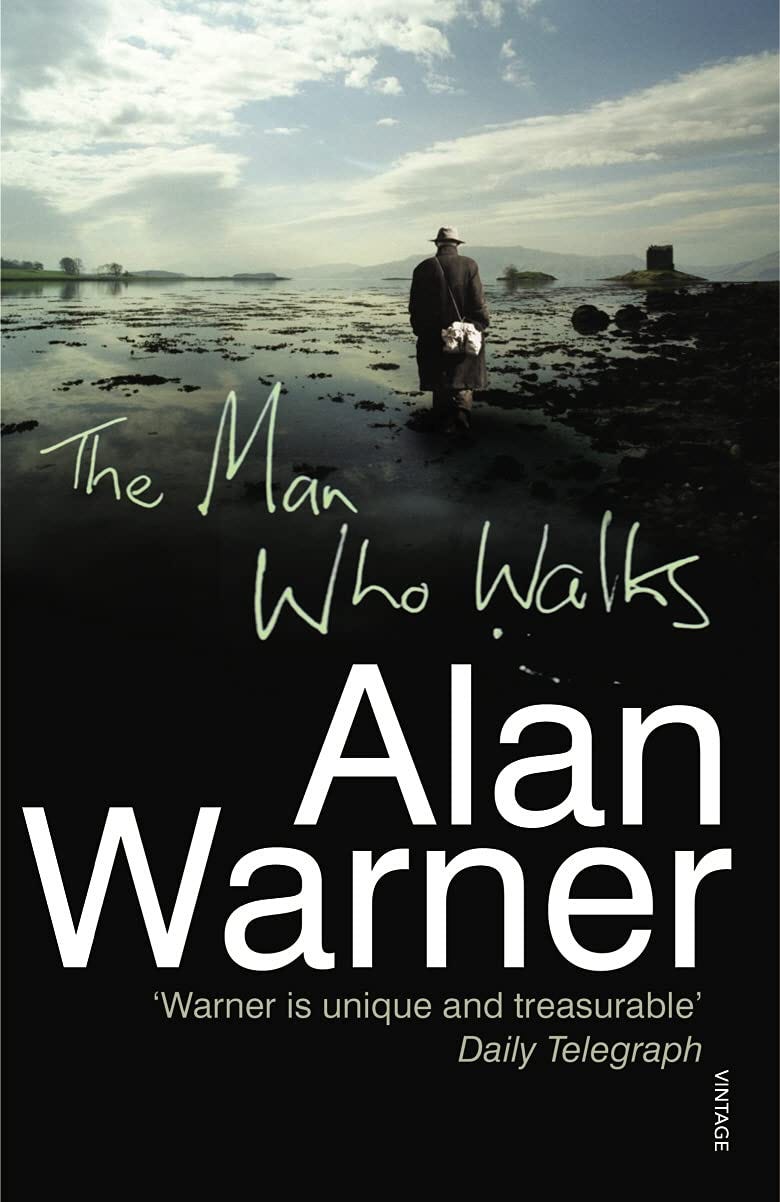

—’It wasn’t just during winters the ghost bags came in, rolling over across the dawn-hard fields from distant miles, tumbling for so long on themselves, inside out or inflated, bloated, as when Murdo in The Albannach found the ballooned-up dog, buried just beneath the sand, or in Gillespie: a living eel emerged from the drowned fisherman’s mouth, from its coiled home in his swollen stomach’: the best-written British novel of the century to date, and maybe also the best. This is part of our search for the best-written books of the century.

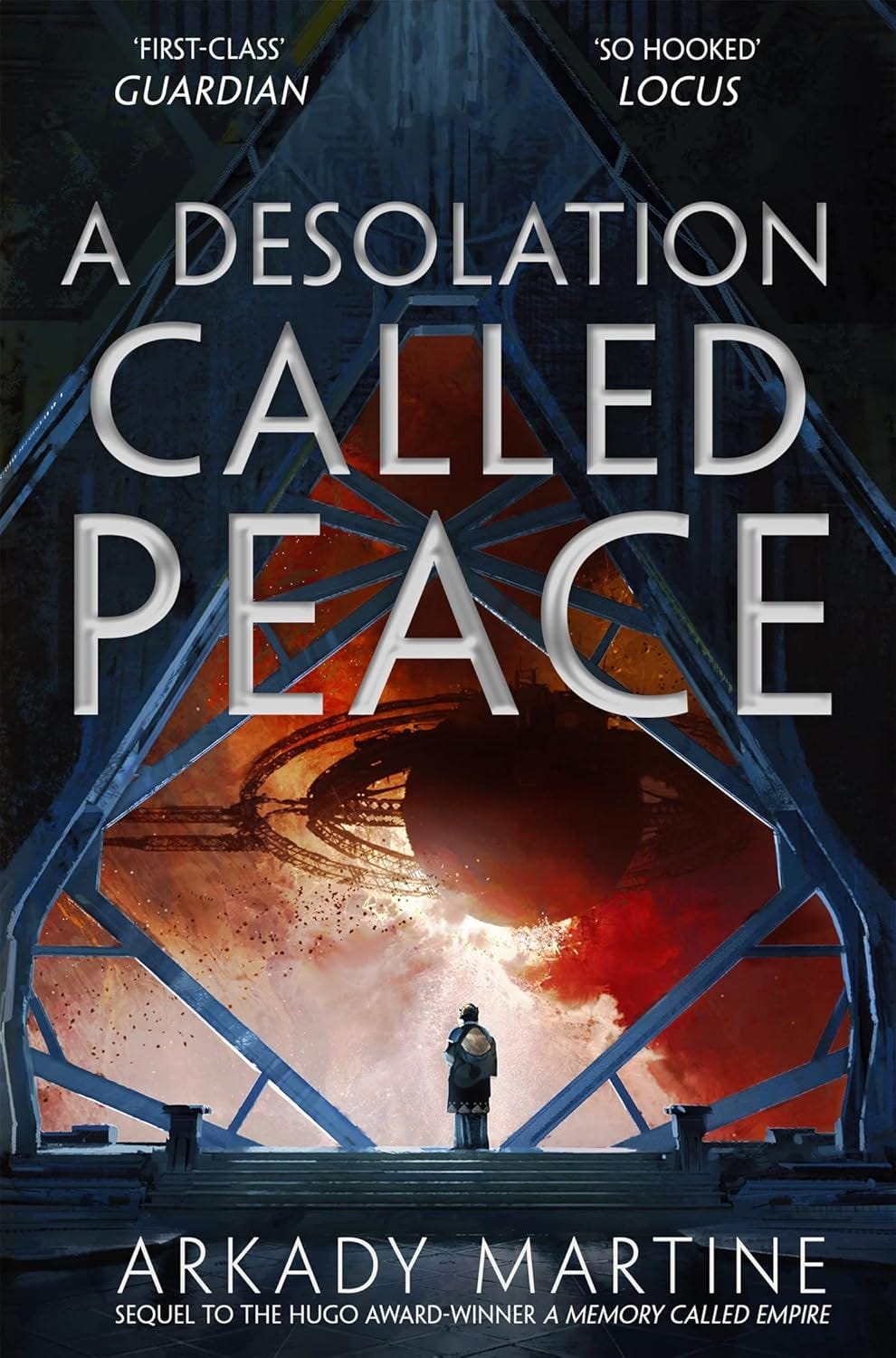

—‘Bodies who think language, who cry with their mouths and leak water from their eyes, who are clawless but vicious in their own hunger to reach out. Who have touched so much of the void-home already, and dwell in it, and have come so very close to the jumpgates behind which are all of our blood-homes, new and old’: the century’s best-written winner of the Hugo Award for best novel.

If you’d like us to consider your own recent release or a work you’ve serialised on Substack, sign up for a paid subscription via the button below and email a copy of your book to auraist@substack.com. If we pick your submission we’ll invite you to write an article on prose style that will be included in the published collection of these pieces.

A paid subscription also gives readers access to our full archive, including exclusive masterclasses on prose style. If you’re already a paid subscriber, thank you for getting behind Auraist and helping to support fine writing and writers.

Or you can join the 20k discerning readers who’ve followed us or subscribed for free access. Please note, though, that after two weeks posts are only available to paid subscribers.

You can also browse our author masterclasses on prose style, picks from the best-written recent releases, from prize shortlists, the best-written books of the century, and extracts from many of these.

We offer a number of benefits to Substackers who recommend or restack Auraist, starting with a six-month complimentary paid subscription. If you’d like to help spread the word about the only publication set up to champion beautiful prose, just email us at the above address.

It wasn’t just during winters the ghost bags came in, rolling over across the dawn-hard fields from distant miles, tumbling for so long on themselves, inside out or inflated, bloated, as when Murdo in The Albannach found the ballooned-up dog, buried just beneath the sand, or in Gillespie: a living eel emerged from the drowned fisherman’s mouth, from its coiled home in his swollen stomach.

Maybe the ghost bags have rolled and bounced all the acres from mini-markets in the next villages, maybe further, from roadside skip bins; perhaps one hundred miles or more from distant cities or freed by some reversing bulldozer on the council landfill?

Rarely seen in the distances, though your eye is alert to all those types of strange horizon movements — some ancient instinct for far and dangerous fringe movement. So you generally never see the ghost bag arrivals. They stir and move on through these territories under cover of night or only when mankind is absent — unless: find the ghost bags at fist light where they ended their nocturnal wanders!: snared on the top barbed-wire of the roadside fences — vibrating, thrumming wild in prevailing westerlies, non-degradable ends ragged, the wind alone and the continual resnaggings of the wayward, tattered ends have masticated the plastic rags down to a texture of sickly grey, dead flesh. Supermarket bags with weathered and fading blue logos from the multinationals, tornoff slicings of scratched polythene from hayricks and black domestic binliners, hopelessly multi-wrapped on the barbed-wire, lodged forever: flapping, twittering deep in the night.

Sometimes he takes his hunting knife and cuts the tethered ghost bags free, watches them chatter off across the fields and suddenly swerve, he is furious at their unpredictability.

.

At dusk, the fresh ploughed fields on either side of the roads make sky darker. Tractors are still working, turning back at cliff edges, letting the full beams of headlights cane out and drum across the surface of the black seas or lochs until they swing, deeply downgear, and shake back unto you. In fair weathers they’ll work all night, and seem quite beautiful in the darkness, halted mysteriously behind a copse, hotly illuminating fore and aft and with lights out on specialised, shaking booms as if some kind of mobile location unit creating a strange new cinema.

When he walks the backroads in daylight, the ahead crows wait till a last taunting moment to lift slow from the macadam before him where they pick at the flattened, sun-dried ruins of their own kind. The crows avoid the ghost bags, spooked by their withering vibrations. The hungrier the crows get the more they come to feed off one another’s corpses and all the more of them burst under the wheels of vans, cars and trucks until a steady theme of increasing slaughter and cannibalism leads him north.

After the scandalous theft of a pub's World Cup cash kitty, a homeless drifter pursues his eccentric uncle: 'The Man Who Walks', up into the Highlands to recover the money - a cool 27,000. The nephew's frantic, stalled progress and other bizarre diversions form this wickedly hilarious novel. But who is The Man Who Walks? Is he simply a water-carrying madman with one glass eye and a fondness for whisky and pony nuts, and who has a physiological inability to handle slopes? Or is he a savant, touched by the hand of God, wandering the back roads along ancient, ancestral tracks? And as the sinister, unstable nephew gains on The Man Who Walks, can it be that it will all end in a field and that this field is Culloden Moor?

RECOMMENDED:

THE HUGO AWARD FOR BEST NOVEL - THIS CENTURY’S WINNERS

2001 J. K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

2002 Neil Gaiman American Gods

2003 Robert J. Sawyer Hominids

2004 Lois McMaster Bujold Paladin of Souls

2005 Susanna Clarke Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell

2006 Robert Charles Wilson Spin

2007 Vernor Vinge Rainbows End

2008 Michael Chabon The Yiddish Policemen's Union

2009 Neil Gaiman The Graveyard Book

2010 Paolo Bacigalupi The Windup Girl; China Miéville The City & the City

2011 Connie Willis Blackout/All Clear

2012 Jo Walton Among Others

2013 John Scalzi Redshirts

2014 Ann Leckie Ancillary Justice

2015 Cixin Liu The Three-Body Problem, Ken Liu (translator)

2016 N. K. Jemisin The Fifth Season

2017 N. K. Jemisin The Obelisk Gate

2018 N. K. Jemisin The Stone Sky

2019 Mary Robinette Kowal The Calculating Stars

2020 Arkady Martine A Memory Called Empire

2021 Martha Wells Network Effect

2022 Arkady Martine A Desolation Called Peace

2023 Ursula Vernon (as T. Kingfisher) Nettle & Bone

The best-written of these is

PRELUDE

TO think—not language. To not think language. To think, we, and not have a tongue-sound or cry for its crystalline depths. To have discarded tongue-sounds where they are unsuitable. To think as a person and not as a wantful voice, not as a blank-eyed hungering beast, not as a child thinks, with only its own self and the cries of its mouth for company. To look outward from the two-ring or three-ring of one of our starflyers, and see every pinpoint light, every fusion-heart star. To see the pattern these stars make in our eyes reflecting the pattern of our eyes in the dark on the old planet. How our eyeshine glowed in the dirt-home, the blood-home! How we closed them and were invisible, dark-scavengers, secret-hunters! How our starflyers glow in the void-home, the light-home of us! How we slip sideways, like a closing eye, and are invisible! To think as a person, with the singing fractal swarm of we, and see these places that we have not yet scavenged, not yet torn open, claws as delicate as surgeon-scalpels, for their secrets!

Oh, the other hunger, the hunger of we that is nothing to do with the body. The hunger of we to reach out.

This body or that body: flesh full of the genes for strength and savagery, flesh full of the genes for patience and pattern-spotting. This body a curious body, an observer body, trained well for celestial navigation and surveying, its claws laced through with the filaments of metal that allow it to sing not only to we but to any starflyer it touches. This body a body that almost did not become we, almost became meat instead, but is we, and sings we, and is a body for making other bodies meat, for making also other bodies with itself: this body full of kits and clever with its hands on the triggers of a starflyer’s energy cannons.

These bodies, singing in the we, singing together of the flesh of bodies who are not we but have built starflyers and energy cannon. Bodies who are meat and cannot sing! Bodies who think language, who cry with their mouths and leak water from their eyes, who are clawless but vicious in their own hunger to reach out. Who have touched so much of the void-home already, and dwell in it, and have come so very close to the jumpgates behind which are all of our blood-homes, new and old.

These bodies sing: the clever meat dies like every other meat, like we do, but it does not remember what its dead meat knew. So we have brought down our sibling-bodies onto one of their planets, not a blood-home but a dirt-home, full of resources to scavenge, and we have rendered them up for usage, the meat and the resources both.

To sing—hunger satisfied. To sing—understanding. Except:

Another body provides counterpoint, a dissonant chord. This body a curious body, an observer body, a stubborn and patrolling body who has slipped sideways in and out of vision in the same sector of void for lo these many cycles and remains a curious body even so. This body sings in the we, sings of a few clever meat bodies that do remember what their dead meat knew. But not all of them. Not all the same knowing. Not like the singing of the we.

To think of a we that fragments! That does not flock, that remembers but could not hold the shape of a murmuration. We sing disturbance and we sing the hunger of reaching-out, to think of fragmentation! We sing, too: What does this clever meat have that we do not? What singing is their singing, that we cannot hear?

And we send our starflyers whirling, whirling close. Close enough to taste.

Publishers Weekly’s Best Books of 2021

Amazon’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy of 2021

Bookpage’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy of 2021

Goodreads Choice Awards Nominee for Best Science Fiction Book of 2021

.

This reads like the opening scene in a western: It wasn’t just during winters the ghost bags came in, rolling over across the dawn-hard fields from distant miles, tumbling for so long on themselves, inside out or inflated, bloated, as when Murdo in The Albannach found the ballooned-up dog, buried just beneath the sand, or in Gillespie: a living eel emerged from the drowned fisherman’s mouth, from its coiled home in his swollen stomach.