1 Fairfield Walk

We lived here – my mum, dad and me – from 1958, the year I was born, until 1970 when I was eleven. My mum was proud of the fact that we lived in an end-terrace house and so were effectively in an unusually extended semi-detached. Even without that enhancing increment of status it was a glamorous terrace. The bricks on the east-facing fronts of all the houses were glazed and in places this glazing was pocked with spider-web cracks: the result of gunfire from the Second World War. The Germans had not only succeeded in crossing the Channel; they had somehow advanced all the way to Gloucestershire, right up Fairhaven Street to the frontline of Fairfield Walk. Even if that is historically questionable it shows how close to home the war was in the consciousness of any boy growing up in the 1960s.

At the back of the houses was a lane with a wide ridge of grass in the middle and weeds at the edges. Halfway along, this unpaved lane met another, similarly puddled, running perpendicular to it, between Fairfield Avenue and Fairfield Park Road. This was where kids from all the nearby Fairfields converged and played. If the war at the front of the houses was in the past, here in the lanes, on the far side of history, it continued unabated. Unsupervised by adults, all our games were war-related. Although overwhelmingly Second World War-derived, the weaponry was ahistoric, sourced from the Wild West of cowboys (six-shooters, holsters) and Indians (bows and arrows, with suckers instead of sharp points), the Crusades (swords, shields, an assortment of plastic armour) and contemporary espionage: James Bond, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Everything which in wartime had been metal was, in our version, remoulded in plastic. I owned both a black plastic Tommy gun and, like many of my friends, a green plastic helmet. Since these helmets protected us from injury it was acceptable to cosh Keith Williams over the head – over his plastic helmet – with my Tommy gun. His helmet did its job, he was unharmed, but the barrel of my gun snapped off and was left hanging from the plastic khaki strap connecting it to the simulated wood-grain of the plastic stock. A coveted weapon had been reduced to bits of angled plastic, one dangling from the other. I was fine but with my gun mortally injured had to return with it to the dressing station called home. My dad glued the gun back together later that evening but thereafter it was fragile – more fragile than it had been before it broke – and had to be handled with a delicacy unsuited to the demands of battle. The war raged on regardless, with a resolve that extended Churchill’s speech about fighting on the beaches and the landing grounds into the arena first of processed food and then natural vegetation. When our Sekiden pistols ran out of ammunition we used frozen peas instead of silver pellets; when these got jammed, because of the peas becoming mushy, we made do with sweater-piercing darts: green chevrons of wally barley that grew in swaying clumps at the lane’s edges.

While the lane was a kind of no man’s land in the sense that it was the almost exclusive preserve of kids, the one conflict that had no place in our games was the First World War. Always present in the realm of memory and relatives – Gary Hunt’s grandad regularly dropped his trousers to show us the gouged pink scars of shrapnel wounds from the Somme – it was entirely absent from the field of play, the lane of fire. Rather than a war with clearly defined sides and goals the ongoing and unwinnable conflict in which we were engaged was a swirl of shifting allegiances in which prisoners were abruptly released, the wounded recovered instantly, and the dead came back to life in minutes, often taking up arms on behalf of the side that had killed them. Whereas in actual war getting shot, wounded, captured or killed were the worst things that could befall a soldier, these were the experiences most actively sought. We wanted to be killed, to roll over and (briefly) die, felt cheated if denied this ultimate proof of full participation in the life of combat. Some uncamouflaged civilian vehicles – mauve Triumph Herald, blue Ford Anglia – splashed slowly through the amphibious puddles but with so little traffic there was no chance of anyone coming to grief. Grazed knees and occasional tears were a minor inconvenience – signs of realism as handkerchief bandages and imagined dressings were applied by girls – and all games were marked by a chaotic lack of malice. The constant noise – shouted orders, cries for ammo, vocalised explosions, the phlegmy rat-a-tat-tat of automatic fire – was audible proof of a deeper tranquillity than could ever be conveyed by silence. To be at war was to be in a state of actively maintained peace, steeped in the contentment of a shared love of all things martial.

Adults eventually came out to call a truce for the night and sound the retreat indoors. Brothers – in arms – went home together, to more games with their siblings; I went home to my mum and dad, to play with my toy soldiers.

More information about the book US/Canada »

UK/Ireland »

Nonfiction titles considered this month

The Acid Queen by Susannah Cahalan

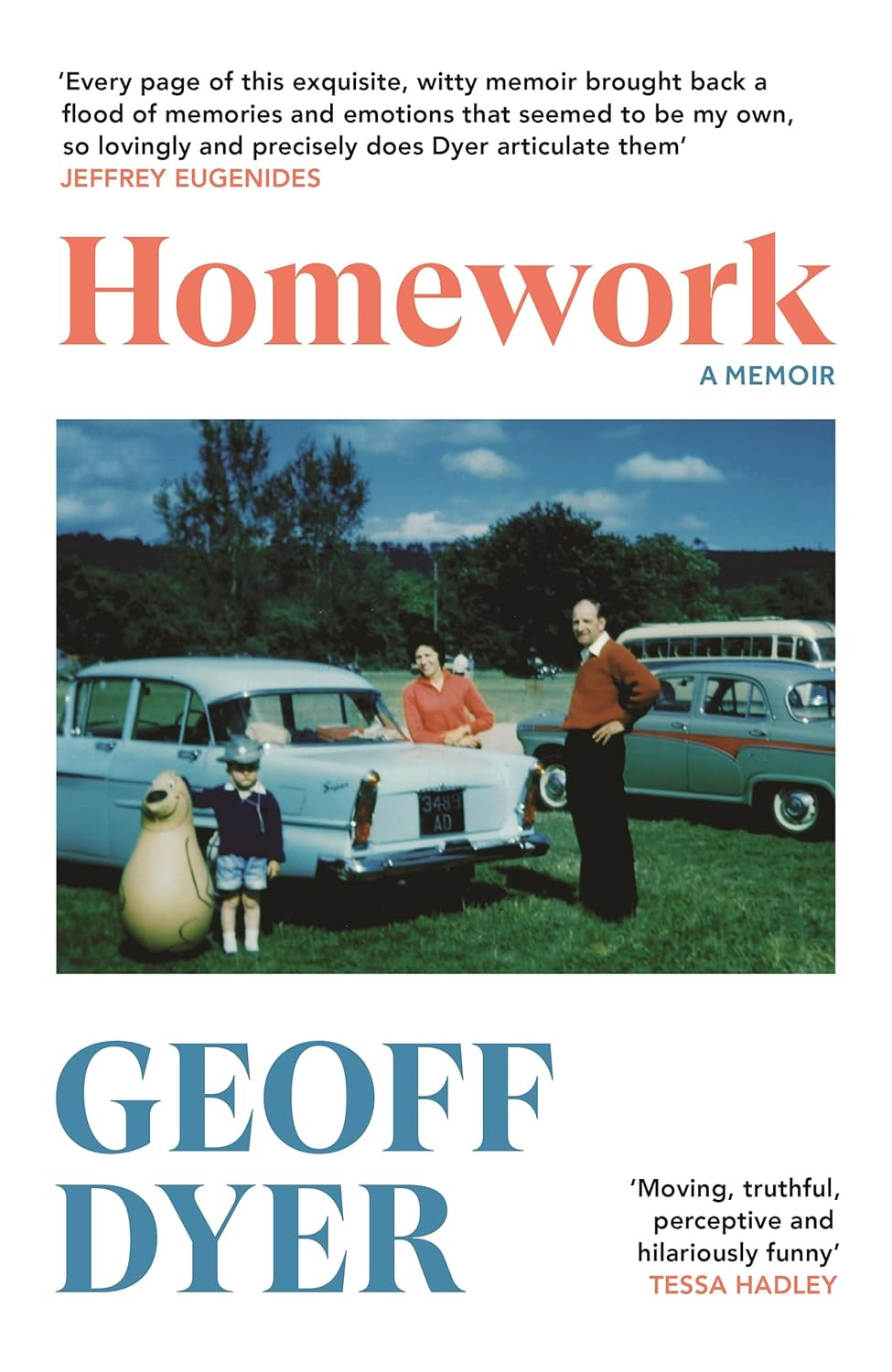

Homework by Geoff Dyer

The Haves and Have-Yachts by Evan Osnos

No Straight Road Takes You There by Rebecca Solnit

The Optimist by Keach Hagey

The Heart-Shaped Tin by Bee Wilson

Mark Twain by Ron Chernow

Red Pockets by Alice Mah

The Nazi Mind by Laurence Rees

Scorched Earth by Paul Thomas Chamberlin

The Lost Orchid by Sarah Bilston

I Regret Almost Everything by Keith McNally

Alive Day: A Memoir by Karie Fugett

Empty Vessel: The Story of the Global Economy in One Barge by Ian Kumekawa

Second Life: Having a Child in the Digital Age by Amanda Hess

We All Want to Change the World by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar & Raymond Obstfeld

The Price of Victory: A Naval History of Britain: 1815-1945 by N.A.M. Rodger

The Intermediaries: A Weimar Story by Brandy Schillace

The Afterlife of Malcolm X by Mark Whitaker

Intraterrestrials: Discovering the Strangest Life on Earth by Karen G. Lloyd

Original Sin by Jake Tapper & Alex Thompson

By the Second Spring: Seven Lives and One Year of the War in Ukraine by Danielle Leavitt

Maya Blue: A Memoir of Survival by Brenda Coffee

When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World by Jordan Thomas

Karl Marx in America by Andrew Hartman

Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie by Dave Hage & Josephine Marcotty

Submitting work to Auraist

We offer writers a fast-growing audience of tens of thousands of discerning readers, including many world-class writers, major publishers and literary agencies, and journalists at the highest-profile publications.

If we publish your work, we’ll invite you to answer our questions on prose style. Your answers will be considered for inclusion in the print publication of these pieces by many of the world’s best writers.

The following submissions are welcome:

Books published in the last year

Works serialised on Substack

Start the process by signing up for a paid subscription below. Then email your work to auraist@substack.com.

We look forward to reading it.