The Goldsmiths Prize for innovative fiction: the best-written work on this year's shortlist

And the best-written previous winner

COMING SOON:

—November is the busiest month for literary prizes, so we’ll be featuring the best-written books from their shortlists, and also from the century’s previous winners of these prizes. To avoid sending you too many posts, we’ll leave the recent releases until December.

—Eleanor Anstruther and Samuél Lopez-Barrantes will be joining me on the 16th of November for a live video discussion of what we mean by the term ‘literary’. All of you are welcome to join us, and you can find more information here, restacks of which would be appreciated.

IN TODAY’S ISSUE

—‘She presumably had teeth at the back of her mouth, but the almost daughter had always avoided being close enough to be able to check, as doing so caused her a vague, pulsing nausea. On the days when the lonely woman spoke too much, the almost daughter could imagine the saliva pooling and foaming in the throat the voice was coming from, and the sensation would then spread out to her own throat’: the best-written work on the shortlist for 2024’s Goldsmiths Prize for innovative fiction, which over the years has had perhaps the highest quality of any English-language literary prize. The winner will be announced on the 6th of November.

—‘We just accept that the past was The Past. We live Now. We live In Light. And when darkness threatens (darkness? Can there ever truly be darkness again?) they simply adjust the chemicals. They just . . . know’: the best-written previous winner of the Goldsmiths Prize. This choice is part of our project to identify the best-written books of the century.

If you’d like us to consider your own recent release or a work you’ve serialised on Substack, sign up for a paid subscription via the button below and email a copy of your book to auraist@substack.com. If we pick your submission we’ll invite you to write an article on prose style that will be included in the published collection of these pieces.

A paid subscription also gives readers access to our full archive, including exclusive masterclasses on prose style. If you’re already a paid subscriber, thank you for getting behind Auraist and helping to support fine writing and writers.

Or you can join the 23k discerning readers who’ve followed us or subscribed for free access. Please note, though, that after a few weeks posts are only available to paid subscribers.

You can also browse dozens of author masterclasses on prose style, hundreds of picks from recent releases and prize shortlists, the best-written books of the century, and extracts from many of these.

Any thoughts related to our picks and masterclasses, or prose style generally? Email them to the above address and we’ll give you a complimentary six-month paid subscription.

Or you can join the 480 Substacks recommending Auraist and receive the same complimentary subscription.

THE SHORTLIST FOR THE 2024 GOLDSMITHS PRIZE

Tell by Jonathan Buckley

All My Precious Madness by Mark Bowles

Parade by Rachel Cusk

Choice by Neel Mukherjee

Spent Light by Lara Pawson

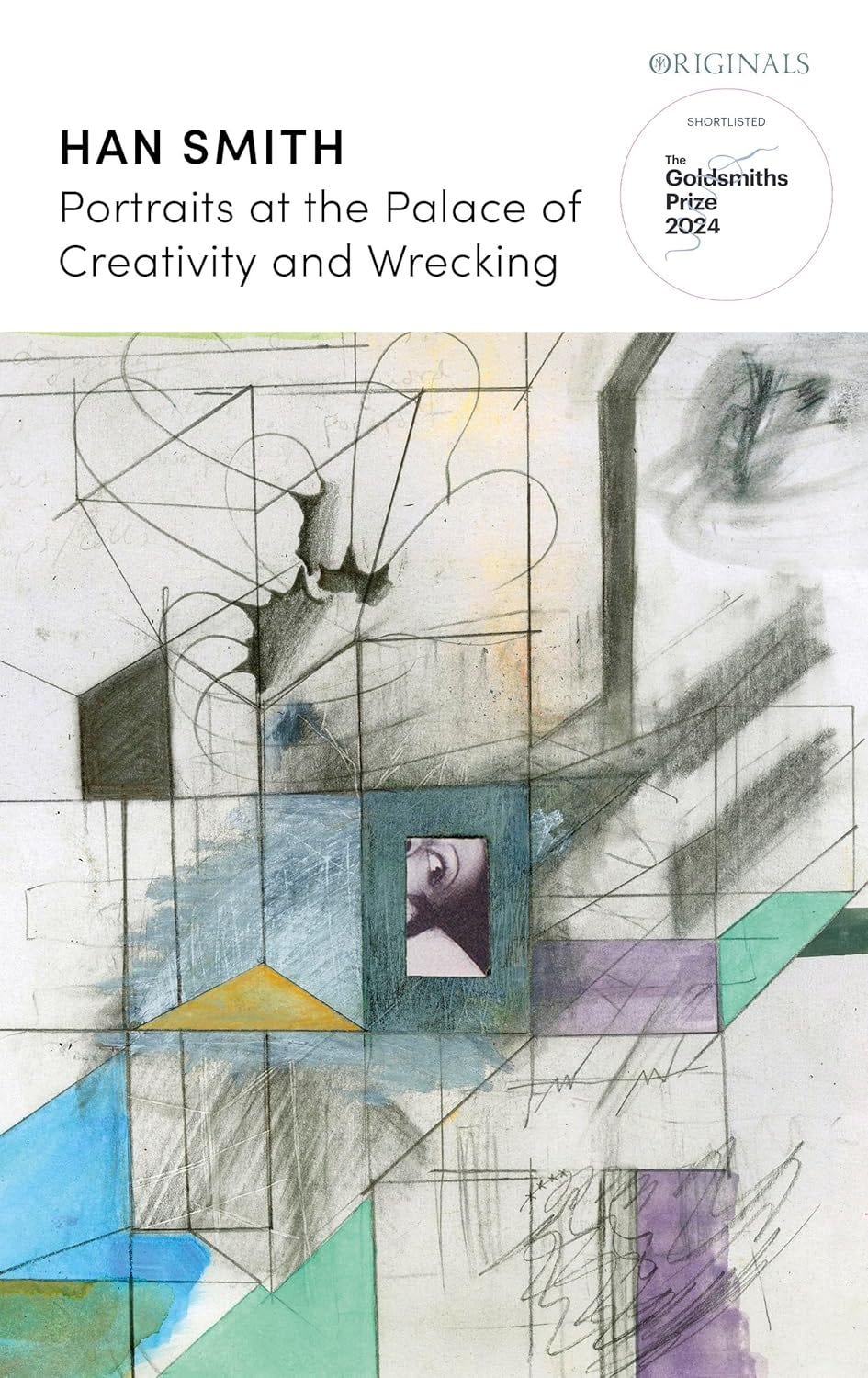

Portraits at the Palace of Creativity and Wrecking by Han Smith

The best-written of these is

Portrait #1

The haunted

This is the portrait of who she used to be. She was a daughter – or rather, she was almost a daughter, because that was just the way things were – and she had always known what kind of cursed place she lived in, to a lesser or greater extent at different times.

She knew broadly, for instance, that her own mother’s grandmother had been sent to the region from a better, cleaner city, in the west of the country and years ago. This was where the story ended: this great-grandmother was dead now and had always been dead, thick in the layers of mothers and past things. She had always been dead but did have something to do with the other woman who lived alone and had no family to visit her on weekends, so that the almost daughter’s family came instead. They had brought her bread, because that was all she asked for, along with potatoes and cheap cabbageheads and onions. The lonely woman was not dead then but very old and had no whole teeth at the front of her mouth. She presumably had teeth at the back of her mouth, but the almost daughter had always avoided being close enough to be able to check, as doing so caused her a vague, pulsing nausea. On the days when the lonely woman spoke too much, the almost daughter could imagine the saliva pooling and foaming in the throat the voice was coming from, and the sensation would then spread out to her own throat. The room the woman lived in smelled of bare skin, and the onions. There were also days the family had come when the woman did not speak at all, or was howling or was not even dressed.

The almost daughter was aware that, like her mother’s mother’s mother, the old woman had also come from the city further west, and had not necessarily chosen to come. She knew that the place the women had ended up in, or had been sent to – the place that was her own town now – had not been a proper town at the time. The schools that she and her brother attended, and also the factories, and the apartment they lived in, had somehow not existed yet. It was difficult to think a lot about this, but the only reason the buildings were now there and solid, and were full of real things like noise and the lifts, was that people like her mother’s mother’s mother and maybe the lonely woman had been sent and not allowed to return. These people had had to remain for so long that all the blocks and lamp posts and the schools had been built and eventually had become a town. If the almost daughter sometimes did think about this, despite the difficulty and despite the fact that she generally had other things to think or not think, there really must have been a huge number of people sent from wherever else and not let back, if a whole life-sized town had ended up being built. At the same time, if so many people had been sent and then had not been allowed to go back, there must have been something and someone to keep them there, and the something must have been very large and strong, and the someone must have been many people, too. Then there was the question of why they had been sent, and why they were not permitted to go back, and this was where things were even harder to keep hold of. In any case, if it had been important and worth thinking so much about, surely someone would have said it all out loud by now.

But there was also the matter of the haunted fields where the athletics contests were held each year. For the almost daughter’s brother this seemed less of a problem, as he was usually actually taking part, in either the long-distance lap run or the hurdle race. One year, he came second in both. The almost daughter was never selected for an event, except once when an error had been made in the high jump and a girl with exactly the same name as hers had qualified, but the error had fortunately been corrected before she had had to sprawl over the pole. Every remaining year, the almost daughter cheered, for her brother and for their school’s other contestants, so it happened that she inevitably heard what the students from other regions said about the fields, in between their own phases of only cheering and shouting. They were the ones who said the word haunted, and sometimes said labour and detained and the other words. They were the ones who pointed to the blunt rows of what had indeed unmistakeably been barracks, before they boarded their buses and left again.

So of course the almost daughter had guessed, though equally naturally, she already knew. Clearly, everybody else knew as well, because why would she – just one boring, almost-person – be special in her guessing or knowing? Still, knowing was slightly different from speaking. Knowing was slightly different, even, from thinking. She sat at the table for dinner every evening with her brother, and with her mother, and her father if he was back from the gas plant, and they discussed when they would visit the lonely woman and bring her the vegetables in bags, until the day they stopped and did not go. The television was always bright and they turned the volume up or down, and they knew and their lips moved on and on. Her own almost face, in a portrait of before.

'Tender and merciless . . . a hallucinatory window into what it means to excavate the past in a world committed to its erasure' ABIGAIL SHINN, Goldsmiths Prize Judge

'Insightful, affecting and assured… Written with a poetry as defamiliarising as it is rich' OISÍN FAGAN

The almost daughter is almost normal, because she knows how to know and also not know.

She knows and does not know, for instance, about the barracks by the athletics field, and about the lonely woman she visits each week. She knows - almost - about ghosts, and their ghosts, and she knows not to have questions about them. She knows to focus on being a woman: on training her body and dreaming only of escape.

Then, the almost daughter meets Oksana. Oksana is not even almost normal, and the questions she has are not normal at all.

Portraits at the Palace of Creativity and Wrecking is the story of a young woman coming of age in a town reckoning with its brutal past, for readers of Milkman and A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing.

RECOMMENDED:

PREVIOUS WINNERS OF THE GOLDSMITHS PRIZE

2013: A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride

2014: How to Be Both by Ali Smith

2015: Beatlebone by Kevin Barry

2016: Solar Bones by Mike McCormack

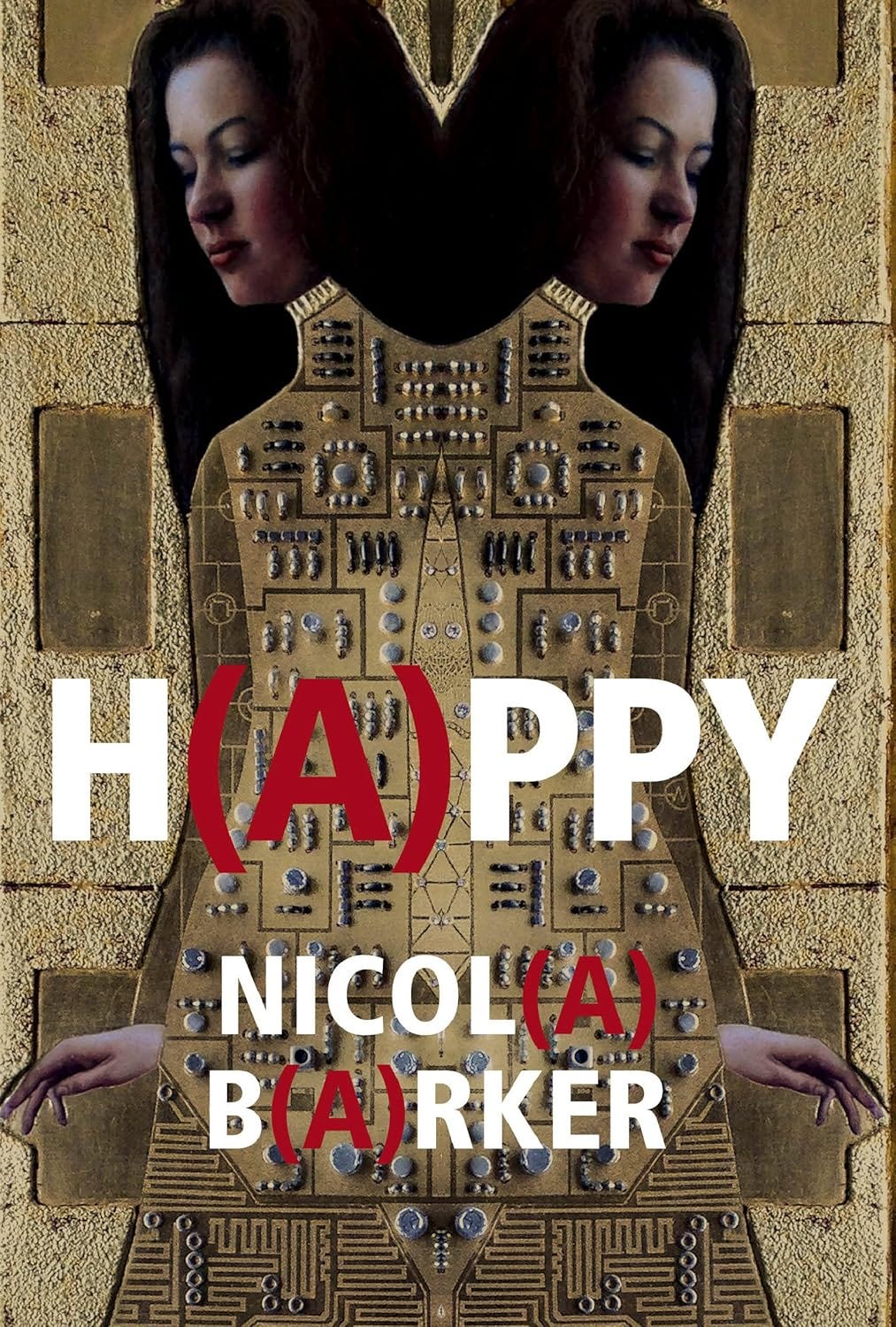

2017: H(A)PPY by Nicola Barker

2018: The Long Take by Robin Robertson

2019: Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann

2020: The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again by M. John Harrison

2021: Sterling Karat Gold by Isabel Waidner

2022: Diego Garcia by Natasha Soobramanien and Luke Williams

2023: Cuddy by Benjamin Myers

The best-written of these is

1 The New Path

After they banded together and saved us from the Floods and the Fires and the Plagues and the Death Cults, the Altruistic Powers actively discouraged The Young from thinking about God. We walked a new path. They called it The New Path. They called it A Path of Light. And The Young were taught various, simple techniques that allowed them to feel at peace. We moved Beyond God. We were taught to celebrate This Moment. And our chemicals were balanced.

We were perfected. We were given just enough choices to make us feel as though we were free, but not so many that our minds (our still-fragile intellects) became overloaded. Doubt ended. The Information Stream was purified. Before, there was filth and it corrupted us. After, there was freshness. There was the smell of newly cut grass. Everything shone. They made us feel innocent again. No – no. They made us Innocent again.

We are Innocent. We are Clean and Unencumbered. Every new day, every new dawn, every new hour, every new minute, we are released once more from the tight bonds of History (the Manacles of The Past). We are constantly starting over and over from scratch. Right here! Right now! A new beginning. A New World. Everything is possible. We are reborn.

I am told that at one time (when there was recorded time – which is apparently a flawed religious concept) everything worked until a certain number was reached and then everything stopped working because nothing could cope with the magnitude of The Number. It was a finite number. All numbers were finite then. Vital resources kept running out and people suffered. Because of numbers. Just numbers. But now numbers are infinite and everything has been mapped and nothing is unknown. Nothing can run out – even life. We are eternal. And we always have enough. Just enough. We do not crave more than enough. We are content. We are In Balance. And we work hard – but never too hard – to stay In Balance. This goal is what fires us, what drives us. We are not encouraged to question how or why – although we are not discouraged from questioning, either. We just accept that the past was The Past. We live Now. We live In Light. And when darkness threatens (darkness? Can there ever truly be darkness again?) they simply adjust the chemicals. They just . . . know.

The chemicals enter us in a multitude of ways. Our environments are sensitive. Our environments are cooperative. Everything is Whole. We are total, universal, all-integrated. We are In Balance. We work (but never struggle) to stay In Balance. And everything functions perfectly. So we no longer have to worry. Sometimes – while we sleep, as we gently dream – they remind us of how it used to be so that we appreciate how good things are now. Now that we are Free From Desire. And we are H(A)PPY to be reminded of this because it reinforces our sense of peacefulness, of calm, of conformity, of equilibrium. They tell us about the lies of The Past. Of how The Young were told that they needed to rebel against the norm in order to feel Whole. That creativity is dependent on struggle and suffering. Of how true happiness could only be felt if we completely abandoned the self to God, or, at the other extreme (The Past was full of such contradictions), of how true happiness was always contingent upon another person or creature’s suffering and pain. That it was somehow ‘comparative’ or ‘competitive’.

Lies. All lies.

When I say ‘they tell us’ I actually mean ‘we tell us’. Because nothing is above us. Nothing is below us. We are In Balance. That is how The System was tooled. We work to stay In Balance. Each of us contributes in our own special way to this goal. I am principally a musician. This is my talent. But I do not focus exclusively on music. Nothing is ever exclusive here. To be exclusive is to exclude. And nothing is excluded. I give my time and my attention and my energy to many causes, to many occupations. I am open. I am humble. I am appreciative. I am grounded.

We have a graph – we call it The Graph – and it shows us how In Balance we are: as a person (our physical and mental health), as a small community (a community of skills, a community of friends, a community of consumers, a community of thought) and as a broader society – as a race, as a planet, as a galaxy. Many graphs, one Graph.

There is a satisfaction – a deep satisfaction – in remaining neatly within the parameters of our various graphs. In keeping things even. And we all strive (but not too hard) for that. Because it makes us H(A)PPY: just to contribute, to be utterly aware, utterly informed, utterly sensitive. Utterly open to everything.

SHORTLISTED FOR THE GORDON BURN PRIZE 2018

LONGLISTED FOR THE WOMEN'S PRIZE FOR FICTION 2018

A GUARDIAN BOOK OF THE YEAR

A TELEGRAPH BOOK OF THE YEAR

AN INDEPENDENT BOOK OF THE YEAR

From the internationally acclaimed, Man Booker-shortlisted Nicola Barker comes a post-post apocalyptic story that overflows with pure creative talent. Imagine a perfect world where everything is known, where everything is open, where there can be no doubt, no hatred, no poverty, no greed. Imagine a System which both nurtures and protects. A Community which nourishes and sustains. An infinite world. A world without sickness, without death. A world without God. A world without fear. Could you...might you be happy there? H(A)PPY is a post-post apocalyptic Alice in Wonderland , a story which tells itself and then consumes itself. It's a place where language glows, where words buzz and sparkle and finally implode. It's a novel which twists and writhes with all the terrifying precision of a tiny fish in an Escher lithograph – a book where the mere telling of a story is the end of certainty.