Nonfiction and Speculative Fiction: the best-written recent releases

Read the opening pages from our picks below

Congratulations to Lorrie Moore whose I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home won the National Book Critics Circle Award for best novel, and to Safiya Sinclair whose How to Say Babylon won the award for best memoir. Days beforehand we chose that novel and memoir as the best-written books on their respective shortlists.

In today’s issue

— Our picks of the best-written recent releases in nonfiction and speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, horror), plus the opening pages from each.

— A brief extract from The Demon Inside David Lynch, which we’ll be serialising later this month.

We’ve now organised the site so you easily access our archives of author masterclasses, picks from the best-written recent releases, from prize shortlists, the best-written books of the century, and extracts from many of these.

If you’d ever like to comment on anything Auraist-related, you can always find us on Substack’s Notes. Restack any of our Notes there, or any of our email posts, and we’ll send you a complimentary paid subscription. Or click the link below to join the hundreds of discerning readers who sign up every week to receive our picks of the best-written books and masterclasses by their authors on prose style.

Thank you again for your support, which is far beyond anything we anticipated when we started, and for liking and sharing our posts to help spread the word that fine writing matters.

NONFICTION RECENT RELEASES

Books considered

All Things Are Too Small Becca Rothfeld

The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness Jonathan Haidt

Heresy: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God Catherine Nixey

Little Englanders Alwyn Turner

Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson James Marcus

Catastrophe Ethics: How to Choose Well in a World of Tough Choices Travis Reider

A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America Richard Slotkin

3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans & The Lost Empire of Cool James Kaplan

How to Win an Information War Peter Pomerantsev

A History of Women in 101 Objects Anna belle Hirsch

Here After: A Memoir Amy Lin

Metaracism Tricia Rose

American Mother Colum McCann with Diane Fole

To Be a Jew Today Noah Feldman

Reading Genesis Marilynne Robinson

No Judgement Lauren Oyler

The Ancient Art of Thinking for Yourself Robin Reames

Says Who?: A Kinder, Funner Usage Guide for Everyone Who Cares About Words Anne Curzan

No Son of Mine: A Memoir Jonathan Corcoran

The best-written of these is

The Bible is a theodicy, a meditation on the problem of evil. This being true, it must take account of things as they are. It must acknowledge in a meaningful way the darkest aspects of the reality we experience, and it must reconcile them with the goodness of God and of Being itself against which this darkness stands out so sharply. This is to say that the Bible is a work of theology, not simply a primary text upon which theology is based. I will suggest that in the early chapters of Genesis God’s perfect Creation passes through a series of changes, declensions that permit the anomaly of a flawed and alienated creature at the center of it all, ourselves, still sacred, still beloved of God. To say that the narrative takes us through these declensions—the Fall and the loss of Eden, then the Flood and the laws that allow the killing of animals and of homicides, then the disruption of human unity at Babel—is not to say that they happened or that they didn’t happen, but that their sequence is an articulation of a complex statement about reality. The magnificent account of the onset of Being and the creation by God of His image in humankind is undiminished in all that follows despite the movement away from the world of God’s first intention—modified as this statement must be by the faith that He has a greater, embracing intention that cannot fail. Within the final mystery of God’s purpose there are the parables of prophets and sages. History and experience are themselves parables awaiting their prophets.

However it came about, this narrative sequence establishes a profound and essential assertion of the sacred good, making pangs and toil a secondary reality, likewise the punitive taking of life. This construction of reality, absolute good overlaid but never diminished or changed by temporal accommodations to human nature, allows for faithfulness to this higher good. Grace modifies law. Law cannot limit grace.

'A work of exceptional wisdom and imagination' DR ROWAN WILLIAMS, DAILY TELEGRAPH

'Rich and provoking... Robinson has masterfully traced a sense of wonder back to its ancient, remarkable source' JULIAN COMAN, OBSERVER

'Reading Genesis is alive with questions of kindness, community and how to express what we so often struggle to put into words' NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE

For generations, the Book of Genesis, included in its entirety here, has been treated by scholars as a collection of documents by various hands, expressing different factional interests, with borrowings from other ancient literatures that mark the text as derivative. In other words, academic interpretation of Genesis has centered on the question of its basic coherence, just as fundamentalist interpretation has centered on the question of the appropriateness of reading it as literally true.

Marilynne Robinson's approach is different. Hers is one of an appreciation of Genesis for its greatness as literature, for its rich articulation and exploration of themes that resonate through the whole of Scripture. She illuminates the importance of the stories of, among others, Adam and Eve; Noah and his ark; the rivalry of Cain and Abel; and the father and son drama of Abraham and Isaac, to consider the profound meanings and promise of God's enduring covenant with humankind. Her magisterial book radiates gratitude for the constancy and benevolence of God's abiding faith in Creation.

COMING LATER THIS MONTH:

We need to accept that an all-time TV catastrophe made by a ten-dimensional demon will reach depths impossible for any three-dimensional being, me certainly included, to get their head around. We therefore need to accept as well that not only will courage be required on this journey but humility too. However far our jaws drop or however wide our minds are stretched—picture Bowman juddering through the vortex in 2001: A Space Odyssey—we must never let arrogance convince us we’ve a true sense of the scale of this abomination.

It’s probable that three-dimensional beings aren’t even supposed to try to comprehend that scale. It isn’t too late to stop reading. Twin Peaks: The Return’s destroyed marriages, engagements, sex lives, friendships, security teams, hairstyles, shoes, toes, ankles, knees, bottoms, minds, entire identities, sobrieties, nonwrestling streaks, reputations, made people apathetic or in one case pleased about some of these destructions, made people authentically despairing about modern corporate culture, turned tranquil Rottweilers into furious maniacs, induced uncanny out-of-body subspace experiences, reduced people to babbling wrecks, made them build dioramas of the town of Twin Peaks in their flat, wallpaper their flat with pages from Mr Morrissey’s novella, and believe the series’ title lettering was beaming down at them from the sky, that its green rays had infected and puppeteered the whole of the Ultraverse.

And even if you make it through more or less unscathed and inside your own skin and not puppeteered by imaginary lettering, you might still find yourself shouting on street corners to alert your fellow citizens to the fact that this show ever existed.

SPECULATIVE FICTION RECENT RELEASES

Books considered

The Book of Love Kelly Link

The Book of Doors Gareth Brown

Shigidi and the Brass Head of Obalufon Wole Talabi

Red Side Story Jasper Fforde

Past Crimes Jason Pinter

The City of Stardust Georgia Summers

A Flame in the North Lilith Saintcrow

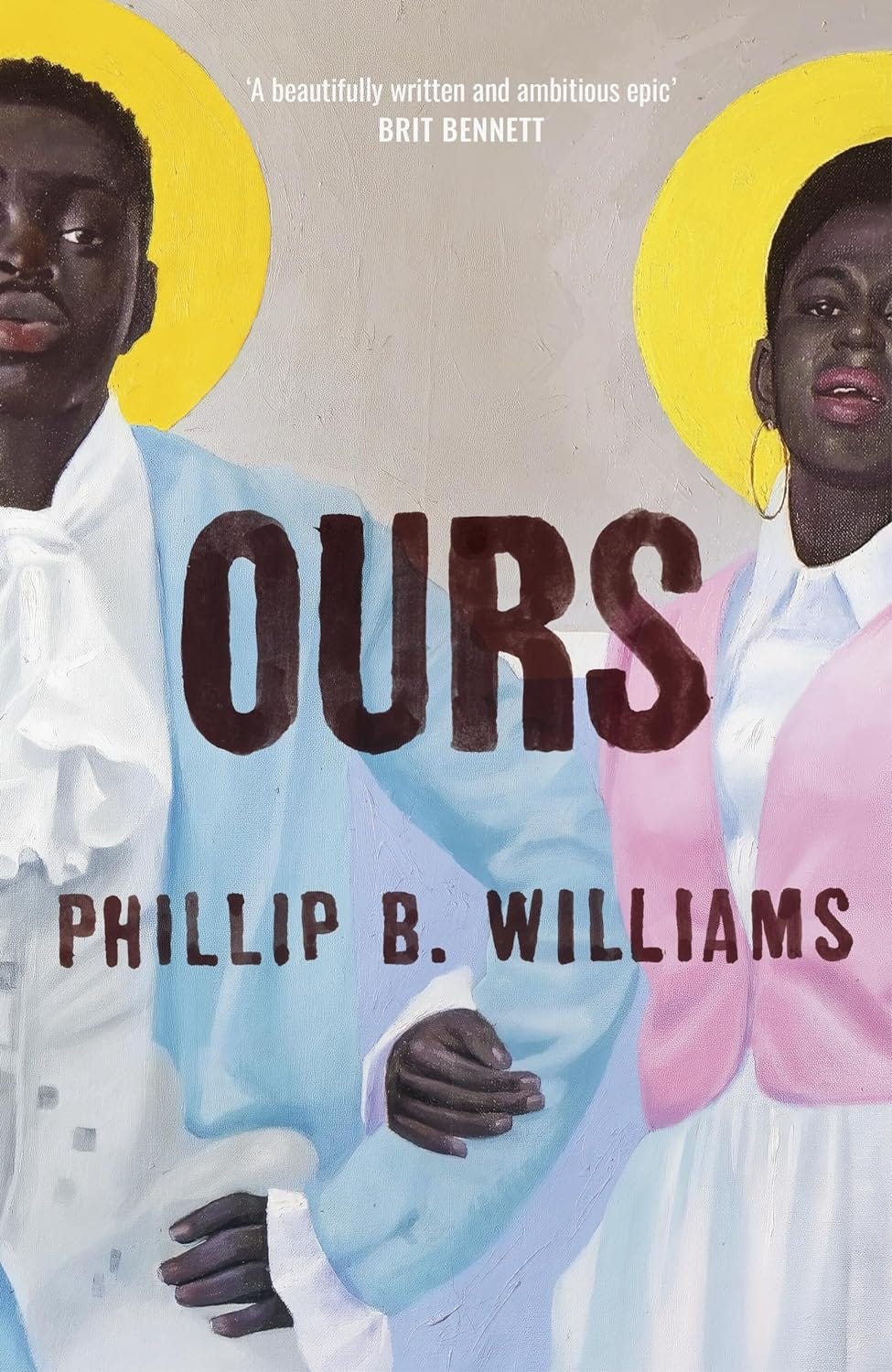

Ours Phillip B Williams

The Other Valley Scott Alexander Howard

The Night Alphabet Joelle Taylor

The Assays of Ataby K.I.S.

The Weavers of Alamaxaby Hadeer Elsbai

Sunbringer Hannah Kaner

The Mars House Natasha Pulley

Annie Bot Sierra Greer

The Warm Hands of Ghosts Katherine Arden

Jumpnauts Hao Jingfang

The best-written of these is

• CHAPTER 1 •

Blood and Light

[1]

Nearly two centuries before the boy who was shot dead at the intersection of First and Bank stood up in his own blood and spoke his name as if it were just given to him, there was a town named Ours, founded by a mysterious and fearsome woman right where the boy had been shot. But perhaps this story begins centuries before then, at the muddy waters of the Apalachicola River, or further back on a ship named the Divider carrying those misunderstood to be the future of slavery to the Western World.

To begin in any of those three places would lead back here, to this boy, age seventeen, fresh out of his junior year in high school, a bottle of orange Fanta rolling and emptying onto the street just feet away from his body from which blood spilled until it stopped, until the boy with his closed eyes opened them with a new mind and breath and understanding that shook him. He had been lying in the middle of the street for three hours with police tape squaring him off from his neighbors, friends, and family. The whole hood had rocked at the sound of the bullets popping off. Then he dropped and they all gathered, hymn-less and weathered, to see yet another one of their youngest take his last breath.

But he stood, his wounds no more than memories as he touched himself where he had been shot, a resonance of pain still there until it, too, departed, the smell of burnt corn bread in the air that someone had abandoned so that he wouldn’t have to lie there for hours alone. Yes, they had all left something behind to stand in that street together, blocked off from touching him and told to “Back up,” had it yelled at them as though they were to have as little care and consideration for the boy as the ones who had shot him.

He dusted himself off and looked around at the faces looking back at him, “What the fuck? My nigga . . .” peeling from a mouth astounded into a beautiful circle. The whole block went quiet except for that question and the loud suddenly sparked up in the crowd despite the cops right there, but who could give a fuck now when the dead have risen?

And he heard his name screamed from someone in the crowd, the voice bright and familiar, but a part of him didn’t recall exactly who had said it. He had two minds now: one in the future and one from the past.

To begin this journey, move backward. The boy’s body returns to the hot asphalt; the orange soda slides back into the bottle, and the blood back into the boy’s warming body; then the boy’s corpse rises and the bullets spin out from the right lung, the neck, the back of the head, the left hamstring, the right buttock, the right triceps, the left scapula, the—; his corpse becomes a living him as flecks of bone restructure and reenter the red-black wound, the broken wet resealed, the white meat sucked back into unbroken muscle, uncooked fat, and closing behind the retreat of the backward-flying bullet; the air the bullets once displaced returns from the curve of its displacement; the silver bullets return into the black gun like an unspeakable organ moving back into its dark element, the explosion of gunfire now the sound of wind hissing, then roaring, then suddenly silent; and the brown finger lifts from its trigger; the boy with his back to the police as the Fanta rises back into his pocket; and further back, weeks ago, the boy is asleep in bed and a small circle of light leaves his body. The legend begins where that light leads. At the end, the boy may teach you his name.

"A beautifully written and ambitious epic about the complexity of freedom. Williams crafts an expansive, original world filled with characters who linger long after the final page" Brit Bennett, author of The Vanishing Half

In the mid-1800s, Saint, an enigmatic and powerful conjure woman, always flanked by a silent companion, travels the South annihilating plantations and liberating the enslaved by means of purposeful violence and powerful magic. She founds a town for those she has freed - and for them alone. They name the town Ours. Surrounded by an impenetrable magical border raised by Saint's powers, Ours is invisible to the outer world and sits blissfully away from prying eyes and violent hands. Saint's mission is to kill slavery - to scourge its damage from the minds of her charges and to keep them safe forever.

Under Saint's watchful eye and away from the terrible weight of their enslavement, the townsfolk become neighbours, friends and lovers. They build each other's homes and care for each other's children. They love and grieve together. Then two mysterious strangers, Frances and Joy, appear, inexplicably crossing the invisible border from the outer world. And soon, Saint's lost past and fateful present begin to coalesce in ways that will either prove Ours' salvation or lay it bare to a world that would destroy it.

Phillip B. Williams' astonishing debut novel is both a sweeping epic shot through with magic, and an intimate, elemental story about what it means to build a community and to try to build a life in the shadow of, and around the damage wrought by, slavery.

At the risk of sounding like an idiot, what is speculative fiction?