The best-written horror novel of the century

Read the opening pages of our pick below ^ Plus Parts 17 and 18 of The Demon Inside David David Lynch

In today’s issue

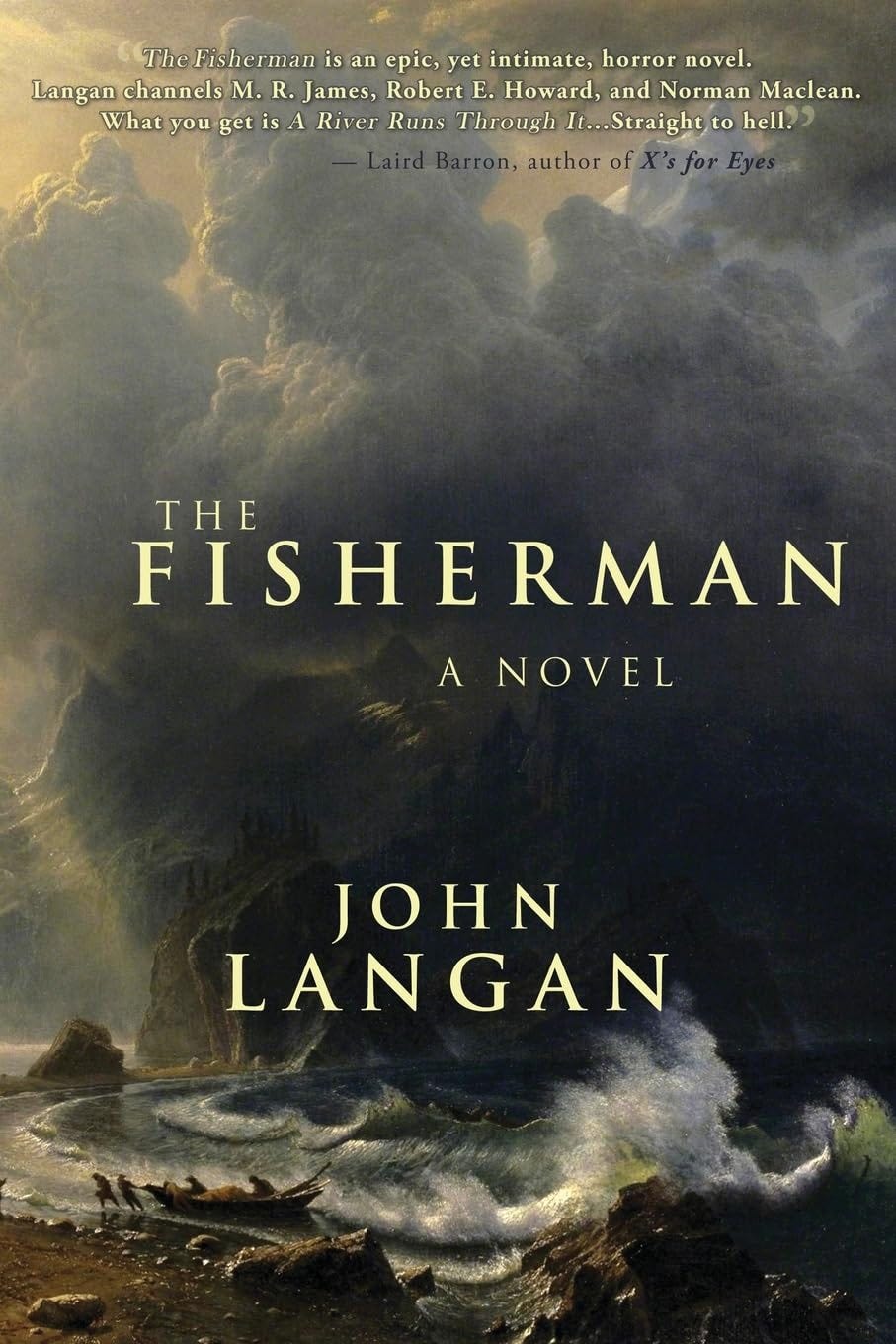

—’It stopped me fishing for the better part of a decade, and although I’ve returned to it once again, there’s no power on earth, or under it, could bring me back to the Catskill Mountains, to Dutchman’s Creek, the place a man I should have listened to called “Der Platz das Fischer’: the opening pages of John Langan’s The Fisherman, our pick as the best-written previous winner of the Bram Stoker Award for best horror novel. This is part of our project to find the best-written book of the century.

The winner of this year’s Bram Stoker Award will be announced on the 1st of June. We’ll soon be announcing the best-written novel on this year’s shortlist, and then we’ll publish a masterclass on prose style by its author.

—‘It was her position, or more like her certainty, that there won’t ever, not on Earth, not anywhere in the Ultraverse, be a work with a greater gap between attempted-funny and actually-funny, which I must say was a little presumptuous of her’: Parts 17 and 18 of The Demon Inside David Lynch: TV Drama’s Worst Fiasco. The entire series is available here, and a free copy of the fully illustrated .epub is available on request at auraist@substack.com. Thanks for the support Auraist readers have already shown this series, and welcome to the new readers joining us from Twin Peaks sites and groups.

You can also browse our author masterclasses on prose style, picks from the best-written recent releases, from prize shortlists, the best-written books of the century, and extracts from many of these.

Recommend Auraist on Substack, or restack or share this post today, and we’ll send you a complimentary six-month paid subscription (if you share it outside Substack just reply to this email with the relevant link). A paid subscription gives readers access to our full archive, and to exclusive masterclasses on prose style by the highest-profile authors. Paid subscribers can comment on all posts, and submit their book for consideration in the genre of their choice.

Or you can join the 16k discerning readers who’ve signed up for free access.

THE BRAM STOKER AWARD FOR BEST HORROR NOVEL

Previous winners

2001 Neil Gaiman American Gods

2002 Tom Piccirilli The Night Class

2003 Peter Straub Lost Boy, Lost Girl

2004 Peter Straub In the Night Room

2005 David Morrell Creepers

Charlee Jacob Dread in the Beast

2006 Stephen King Lisey's Story

2007 Sarah Langan The Missing

2008 Stephen King Duma Key

2009 Sarah Langan Audrey's Door

2010 Peter Straub A Dark Matter

2011 Joe McKinney Flesh Eaters

2012 Caitlin R. Kiernan The Drowning Girl

2013 Stephen King Doctor Sleep

2014 Steve Rasnic Tem Blood Kin

2015 Paul G. Tremblay A Head Full of Ghosts

2016 John Langan The Fisherman

2017 Christopher Golden Ararat

2018 Paul G. Tremblay The Cabin at the End of the World

2019 Owl Goingback Coyote Rage

2020 Stephen Graham Jones The Only Good Indians

2021 Stephen Graham Jones My Heart is a Chainsaw

2022 Gabino Iglesias The Devil Takes You Home

The best-written of these is

I

How Fishing Saved My Life

Don’t call me Abraham: call me Abe. Though it’s what my ma named me, I’ve never liked Abraham. It’s a name that sounds so full of itself, so Biblical, so… I believe patriarchal is the word I’m after. One thing I am not, nor do I want to be, is a patriarch. There was a time I thought I’d like at least one child, but these days, the sight of them makes my skin crawl.

Some years ago, never mind how many, I started to fish. I’ve been fishing for a long time, now, and as you might guess, I know a story or two. That’s what fishermen are, right? Storytellers. Some I’ve lived; some I’ve had from the mouths of others. Most of them are funny; they bring a smile to your face and sometimes a laugh, which are no small things. A bit of laughter can be the bridge that lets you cross out of a bad time, believe you me. Some of my stories are what I’d call strange. I know only a few of these, but they make you scratch your head and maybe give you a little shiver, which can be a pleasure in its own way.

But there’s one story—well, it’s downright awful, almost too much to be spoken. It happened going on ten years ago, on the first Saturday in June, and by the time night had fallen, I’d lost a good friend, most of my sanity, and damn near my life. I’d come whisker-close to losing more than all that, too. It stopped me fishing for the better part of a decade, and although I’ve returned to it once again, there’s no power on earth, or under it, could bring me back to the Catskill Mountains, to Dutchman’s Creek, the place a man I should have listened to called “Der Platz das Fischer.”

You can find the creek on your map if you look closely. Go to the eastern tip of the Ashokan Reservoir, up by Woodstock, and backtrack along the south shore. It may take you a couple of tries. You’ll see a blue thread snaking its way from near the Reservoir over to the Hudson, running north of Wiltwyck. That was where it all happened, though what it all was I still can’t wrap my head around. I can tell you only what I heard, and what I saw. I know Dutchman’s Creek runs deep, much deeper than it could or should, and I don’t like to think what it’s full of. I’ve walked the woods around it to a place you won’t find on your map, on any map you’d buy in the gas station or sporting-goods store. I’ve stood on the shore of an ocean whose waves were as black as the ink trailing from the tip of this pen. I’ve watched a woman with skin pale as moonlight open her mouth, and open it, and open it, into a cavern set with rows of serrated teeth that would have been at home in a shark’s jaws. I’ve held an old knife out in front of me in one, madly trembling hand, while a trio of refugees from a nightmare drew ever-closer.

I’m running ahead of myself, though. There’s other things you’ll need to hear about first, like Dan Drescher, poor, poor Dan, who went with me up to the Catskills that morning. You’ll need to hear Howard’s story, which makes far more sense to me now than it did when first he delivered it to me in Herman’s Diner. You’ll need to hear about fishing, too. Everything’ll have to be in its proper place. If there’s one thing I can’t abide, it’s a poorly put-together story. A story doesn’t have to be fitted like some kind of pre-fabricated house—no, it’s got to go its own way—but it does have to flow. Even a tale as coal-black as this one has its course.

You may ask why I’m taking such care. Some things are so bad that just to have been near them taints you, leaves a spot of badness in your soul like a bare patch in the forest where nothing will grow. Do you suppose a story can carry away such badness? It seems a bit much to hope for, doesn’t it? Maybe it’s true for the little wrongs, you know, the kind of minor frustrations that you’re able to turn into funny stories at parties. For what happened at the Creek, though, I doubt there’s such a transformation waiting. There’s only transmission.

And there’s more to it than that. There’s the tale Dan and I heard in Herman’s Diner. Since Howard told what happened to Lottie Schmidt and her family, some ninety years past, I’ve been unable to shake it. You could say his words stuck with me, which would be the understatement of the year. I can recall that tale word for word, as could Howard from the minister who told it to him. Without a doubt, part of the reason for the vividness of my memory is the way that Howard’s story seems to explain a good deal of what happened to Dan and me later that same day. That tale about the building of the Reservoir and who—and what—was covered by its waters, prowls my brain. Even had we heeded Howard’s advice and avoided the creek that day—Hell, had we turned around and headed back home as fast as I could drive, which is what we should have done—I’m convinced what we heard would still have branded itself on my memory. Can a story haunt you? Possess you? There are times I think recounting the events of that Saturday in June is just an excuse for those more distant events to make their way out into the world once more.

‘Illusory, frightening, and deeply moving, The Fisherman is a modern horror epic.’ Paul Tremblay

In upstate New York, within the woods, Dutchman’s Creek flows out of the Ashokan Reservoir. Steep-banked and fast-moving, it offers the promise of fine fishing, and of something more, a possibility too fantastic to be true.

When Abe and Dan, two widowers who have found solace in each other’s company and a shared passion for fishing, hear rumours of the Creek and what might be found there, the remedy to both their losses, they dismiss them. Soon, though, the men find themselves drawn into a tale as deep and old as the Reservoir.

It’s a tale of dark pacts, of long-buried secrets, and of a mysterious figure known as the Fisherman. It will bring Abe and Dan face to face with all that they have lost, and with the price they must pay to regain it.

‘An epic, yet intimate, horror novel. Langan channels M. R. James, Robert E. Howard and Norman Maclean. What you get is A River Runs Through It… straight to hell’ Laird Barron

‘Reading this, your mouth fills with worms. Just let them wriggle and crawl as they will, though―don’t swallow. John Langan is fishing for your sleep, for your soul. I fear he’s already got mine’ Stephen Graham Jones

The Demon Inside David Lynch states that the celebrated director was possessed by a ten-dimensional entity that went on to make Twin Peaks: The Return. Obviously this is fiction, satire.

Rampant Cheesiness

A useful way to view The Return is that except for some of Parts 3 and 8 it’s a severe instance of cheesiness. Had Andy Warhol risen from the dead and made the series he’d probably have given some lines to gay characters and maybe wouldn’t have mentioned his risen-corpse’s erections, but he might well have given us similarly ill-conceived, poorly scripted, poorly lit, farcically acted, farcically paced, dead-air-filled, incoherent, rampant cheesiness.

The original Twin Peaks was deliberately cheesy at times, but this was more than balanced out by its scenes of terror, pathos, and generosity—its sincerity. The Return, however, is deliberate cheese from the highest level to the lowest. It doesn’t just feel rotten but comprehensively, methodically so, because more or less every important artistic decision has been informed by a sensibility that wallows in corniness, artifice, frivolity, over-the-top gimmickry and flamboyance, and just plain wrongness. The retcon, all that’s happened then turning out to be some guy’s dream, and the giggles at characters’ torment are the sort of trash thrown up by an aesthetic of childish cheesiness and other so-bad-it’s-good. The boggingness of the series nearly always appears to have a titter behind it regarding any unzany expectations from its audience, and that titter is the cheesy sensibility.

Men like César did manage to watch it in a spirit of so-bad-it’s-geeenius, because these men love their cheese, as do fashion students, installation artists and similar types whose tolerance for The Return was far higher than average. Because the fact is that many people don’t enjoy cheesiness, let alone seventeen hours of the stuff. Les says it reminds him too much of relapses, of knowing the urge is idiotic, immature, corny, crosses a Line, but acting on it anyway.

I don’t find a lot wrong with provocative so-bad-it’s-good in reasonably sized doses. Just before I quit the drink a crew of us found ourselves in Villa de Vallecas in a pretty rough club. We’d been wasted for hours and when the DJ played Pharrell Williams’ ‘Happy’ César jumped up on our table to dance and wiggle his buttocks in my face. It was funnyish in a daft, messy-all-day-bender sort of way. Then he approached the table of some nearby growlers, jumped onto it and wiggled his bottom near the growlers’ faces. Drunkenly purple-faced growlers, six of them.

But they took his provocations well, and some got up to dance alongside him while others pretended to fondle his wiggling buttocks. When ‘Happy’ ended and the DJ played Kylie’s ‘I Can’t Get You Out of My Head’, César decided to keep dancing up there on that table. Now no purple-faced growler was pretending to feel his buttocks. But he continued to dance and wiggle them in their faces.

César needed fifteen stitches in his own face that night and has, I suspect, never again planted his bottom in anybody’s face. The point being, again, that inflammatory so-bad-it’s-good requires discipline. (César and the growlers are a handy metaphor for other things as well, e.g. a few of our major political and cultural woes).

However you look at it, The Return is the unfunniest work of the last 300,000 years. If you doubt this it’s likely because you’ve never watched the series, which has more moments and touches that are supposed to be funny but aren’t than anything else ever made. It also has a higher ratio of attempted-funny to actually-funny, somewhere in the high three figures, and sinks remarkably low in its hunt for laughs, yet also has a high conceit of its funniness.

You know when you watch a stand-up comedian lose their touch but keep plugging away until they’re right down there with the desperate galoots wisecracking about wheelchair access, obescity, and trans-rape, yet carry themselves as though they’re Bill Hicks? This feels similar but many times worse, and was an element of The One that really desolated Ella. After we watched its unfunniest episodes, grappling with my own One became for days gynecologically impossible. It was her position, or more like her certainty, that there won’t ever, not on Earth, not anywhere in the Ultraverse, be a work with a greater gap between attempted-funny and actually-funny, which I must say was a little presumptuous of her. Nonetheless the show is aeonally unfunny, and has hours of dead air to help you experience this to its full shoe-wrecking, grappling-wrecking extent.

Even leaving aside all its other defects, its unfunniness alone would make it the worst art project of the century. There can’t be many works in history so unfunny they delay your grappling by half a week, bring a hot lump to your throat, and make every atom of the cosmos feel like it’s quietly snarling with malevolence. That’s a whole different level of unfunny to The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas or The Boat That Rocked.

In fact we’re in the same situation with unfunny as we were with awful. We need a word more terrorised, more Lovecraftian, to accurately describe the savagery of the series’ onslaught of failed humour, to convey those fogbanks of supernatural sorrow and despair the two of us used to feel in our skulls, whatever room we were watching in, and the universe itself, fogbanks whispering of a quick mutual wrist-slash in the bathtub to bring the onslaught to an end.

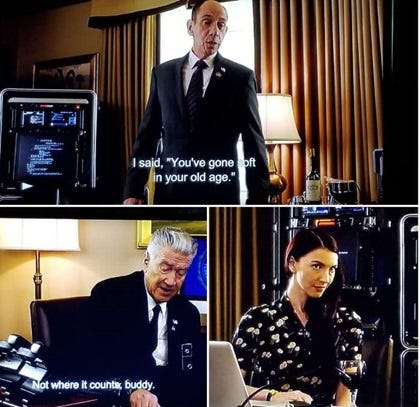

There is a moment in The Return that we did find inanely funny, though, just about. This is out of hundreds of attempts at such humour, true, but even so it’s not completely unfunny when Gordon Cole looks at a photo of Mount Rushmore and says, ‘There they are, Albert, faces of stone’, and soon afterwards we get close-ups of the FBI Deputy Director’s craggy face.

Now fair enough, a segment that makes viewers appraise the writer-director-producer-star-hermit’s own face, with more than enough time for sketching the hermit’s features, is still pretty grim, and ‘faces of stone’ does equate Cole and the auteur self-cast in the part with some of the greatest US presidents in history and is therefore yet another twinkle in the constellation of egomania that attends this character and self-casting. The line and close-ups are still in the outreaches of funny, however, more or less, and don’t quite bring on, as do those hundreds of failed attempts, tightly clamped body parts, lumpy throats, wrecked shoes, and existential heebie-jeebies.

An instance that had César gleefully scattering phlegm and meth crystals around his hut as he watched on his phone is the scene in which the Alex Jones/Neil Breen parody Dr Jacoby, played by Russ Tamblyn, spraypaints shovels gold and leaves them hanging up to dry. The joke here is an acknowledgement that The Return is so tedious it’s similar to watching paint dry (and we’ve already endured the young lovers Sam and Tracey, played by Benjamin Rosenfield and Tracey Barberato, tediously watching a glass box in which, like the show making these jokes about its own tediousness, nothing of interest happens). You get the joke, you rub your sinuses or toes, then the show keeps tediously repeating this latest tedious joke on the subject of its own tediousness as more and more shovels get painted, and you start wondering where Ella keeps her razor blades.

As with much of this series it resembles the worst conceptual art. You get the idea, it’s hoachingly self-involved and not particularly interesting or witty, the idea gets repeated César’s-buttocks-style, and César types rhapsodise over it while you yourself feel little but irritation at the artist for wasting your time.

And even if those hundreds of attempts hadn’t failed, persistent cheesiness for hours and hours is highly unlikely to make a decent work of art. Nearly twenty hours of full-on cheese are very hard going because past a point so-bad-it’s-good becomes so-bad-it’s-aggravating, as those growlers and César will confirm.

And it doesn’t matter if you want to pastiche a soap opera from thirty years ago or whatever other mightily relevant foe you have in your sights, or to portray temporality as a Möbius strip, or to follow some other ‘idea to the end’, as Mr Lynch often put it. Some ideas shouldn’t be followed to the end, because they’re cheesy garbage. And two of these are clearly Cooper’s zip back in time to rescue Laura, and it all turning out to be Richard’s dream. And the Twin knew exactly how garbage they were and that’s why it jumped in with both demonic hoofs.

A Festival of Fetishes

We need to get out of the way the Greying Manbun argument that people hate The Return because they wanted it to resemble the original Twin Peaks. If throughout its style had resembled the 1945 atomic-explosion and 1956 menacing-Woodsmen sequences in Part 8, its only genuinely radical episode and the one furthest from the first two seasons, most haters would have been as happy as the Manbuns, because those sequences are like the Manbuns claim some of the finest television ever broadcast. High stakes allied to likeable or fascinating characters, engaging story developments, gorgeous visuals and sound design that result in a spell being cast, suspension of disbelief and the viewer’s submergence in the unfolding dream, leading at last to a sense of what we’re watching actually mattering—Part 8 is the hole-in-one that makes the 1000+ score for the eighteen-episode production all the more remarkable. It’s the one episode not dominated by cheesiness, and in a counterintuitive way we’ll look at later on, its very excellence is key to the Twin’s project of making the worst piece of art ever seen.

Suspension of disbelief, a core marvel of fictional narrative, does occur when you watch The Return but only in the case of most of Part 8. Of the remaining 960 minutes or so, our belief was suspended for precisely none. The fourth wall isn’t so much broken as barely constructed in the first place. The series’ prevention of suspension of disbelief throughout those minutes is absolute and probably unmatched in TV drama.

This prevention is ensured in a number of ways, each of which would likely have achieved it by itself. For a start, rampant cheesiness makes suspension of disbelief impossible. When so many elements have an undercurrent of Look at how silly this show is! Creators, actors, crew, viewers, aren’t we all being just outrageously naff? Imagine anyone being crass enough to fall for any of it! we are liable to take them at their word and see not characters and events we can believe in and care about but droves of boomer and gen-x actors being silly and naff for scene after scene, hour after hour for five months, and as with many purveyors of in-your-face cheesiness, offputtingly self-pleased. The effect’s a little like those invasions of early-‘70s TV chatshows by mobs of hippies who flicked the ears and mussed the hair of the presenters and guests and studio audiences, and sang nursery rhymes and threw Dayglo paint around, except in this case many of the goofy self-pleased self-ironists are nearer eighty than twenty.

Suspension of disbelief is also made impossible by the greatest drama of the decade’s rampant contempt and ultimate kookiness. So much misanthropy allied to more or less nonstop extreme peculiarity prevents what’s onscreen being a world you can believe in. But the fact that it’s a world you cannot believe in makes the misanthropy seem even worse. There is nothing persuasive about this misanthropy. No attempt is made to justify it. All you get is a reclusive showrunner exhibiting contempt for dozens of different types of people and not caring how valid the people watching find this. The human race is frequently risible or despicable and that’s that, the greatest drama of the decade informs us, and the humans watching just have to accept it.

Meanwhile the ultimate kookiness prevents this being a world you can believe in but is itself made even more repellent by the very implausibility of this world. Unlike in Lynch’s mid-career works, there is no attempt to make the strangeness appear believable, to cast an artistic spell in which we’re at first shocked by the strangeness but then in time persuaded that events could indeed unfold this way. All we get instead is implausibly extreme zaniness after implausibly extreme zaniness for nearly as long as our world takes to rotate on its axis, and apart from Tim Kreider no one’s suggested a non-demonic rationale for the extremity, even compared to the zaniest previous major works of Mr Lynch.

The acting also ruins any chance at suspension of disbelief the way it does in a bad school play. Jim Belushi’s stated that he had no idea what was going on in his scene in the sheriff’s office where Green Glove defeats BOB, and throughout the series similar confusion is evident in many of the other actors.

Then there’s singer-songwriter Chrysta Bell’s casting as FBI Special Agent Tammy Preston, who’s portrayed as never less than impressed by a handsy boss more than twice her age, the auteur-played Gordon Cole who leers at her buttocks as she slinks away in high heels etc. And in the finale Tammy’s face is edited in to provide a not unimpressed reaction when in one of the Twin’s many cruel jokes, this time mocking Mr Lynch’s bodily and volitional impotence, Cole declares in an FBI office that he’s not soft ‘where it counts’, a line that had Stanley the Rottweiler rolling around on Ella’s floor whimpering.

Bell is a talented musician but not a talented actress. There are dozens of weak performances in The Return but Bell’s unsurprisingly draws the most criticism. It’s maybe not quite porn standard or Chica standard but it is worse than you’d witness in many secondary-school plays. She appears flummoxed nearly every time she’s onscreen, out of her depth, like a benzo’d trout in a hall of mirrors. She has a pouty and sultry way of talking in interviews about her music and attempts the same pouty sultriness in her lines as top FBI agent Tammy. But she doesn’t only come across as pouty and sultry. She comes across as baffled, contrived, self-conscious and spaced-out, that is, the way you or I would come across if we suffered the degradation of being cast in a TV drama broadcast across the world. It’s unpleasant to watch and brings to mind Citizen Kane’s opera-ruining mistress. The Return is a disaster not just because it drags and looks ugly and the dialogue mings and so on, but because throughout there are also these intimations of demonic cruelty.

Persistent refusal or breaking of suspension of disbelief was once a worthwhile technique for narrative artists, if the payoff was sufficient. But the last time that was really the case was decades ago, and the Twin designed the show to con everyone into thinking former ‘60s student David Lynch chose to stuff it with flogged-to-death ‘60s filmschool silliness.

This helps explain the show’s oddly Austin Powers feel, with Mr Lynch left resembling a postmodernist Dr Evil who’s travelled forwards decades in time and announced not a demand for ‘One million dollars’ but rather his breakthrough of ‘Deliberately poor acting. Get a load of this, world: I’m going to prevent suspension of disbelief.’

Despite what the Césars claim, The Return as a whole is not an avant-garde work. It’s as obscurantist, transgressive and soporific as the worst artschool installations, but apart from the cosmic-ocean parts of the third episode and the twentieth-century parts of the eighth there’s little freshness, or at least little we can admire. Instead what we get are this hermitic Dr Evil’s rehashes of ‘60s filmschool so-bad-it’s-good like deliberate cheesiness, zaniness, poor acting, boredom, transgression, and refusal of suspension of disbelief.

Which would matter less if this refusal did not sacrifice one of fiction’s finest effects. Suspension of disbelief is a sacred function of narrative art, like tonality in music, with a curious similarity to the recovery maxim fake it till you make it, the idea that newcomers should turn up at meetings and pretend to believe the cult-like dogma and gibberish on display, as they see it, until one day they find they’ve cleaned up their act and become a believer.

And suspension of disbelief is difficult to achieve to the extent that Mr Lynch managed earlier in his career. At his peak he wove dreams that suspended our disbelief more effectively than nearly anybody else, all the more impressive considering the abnormality of the portrayed worlds and psychic states. Big Fish indeed, to quote Lynch himself, especially compared to the fousty tiddlers of po-mo conceptualising. Artists who mess with this too much are therefore playing a riskier game than many of them appear to realise, and to make it worthwhile had better be cooking some tasty and nutritious Big Fish.

Many of us struggle to suspend our disbelief in fictional narratives these days, for reasons that haven’t yet been established or even that widely addressed, though one factor has to be the web, what Ella called el zumbido, the drone. If you spend your time online routinely maintaining your disbelief against perhaps the most powerful lie machine ever invented, your brain will likely find it difficult to change gear for fiction and suspend that sanity-preserving maintenance of disbelief.

Nevertheless some of the best shows and films do still manage to get us over this hump by working hard at doing so. The Return doesn’t even try, though, with the result that yet again Mr Lynch is made to look a classic male boomer balloon lost in and therefore sunk by his fetishes and compulsive brooding about them.

Because what happens to a work of fiction when suspension of disbelief is banished? What are we left with if we are seldom allowed to pretend the events or characters are real? We’re left with little but the accumulated opinions, fetishes and speculations of the artist. And this does not reflect well, to say the least, on David Lynch, who ends up looking as though he was given an enormous budget by Showtime to make a third season of Twin Peaks with storylines and characters the audience could engage with, but instead served up a five-month Festival of My Godly Yet Curiously 4Channish Fetishes About My Career, My Penis, Hot Young Chicks, Hags, the Comic Potential of Disabled Men Tied to Chairs, Pam Ewing’s Dream in the 1986 Season of Dallas, Time As a Möbius Strip, Nuclear Warfare, and You Unevolved Lowlifes^^ (see next section).