‘The real choice is between being interestingly musical and boringly musical’: Francis Spufford on prose style

Plus more of the best-written nonfiction of the month ^ And Parts 10 to 14 of The Demon Inside David Lynch

A jumbo teapot that releases puffs of steam containing the voice of a poorly imitated David Bowie. A still from Twin Peaks: the Return.

In today’s issue

—'Beautiful sentences at ugly moments would be… bad’: Spufford’s discussion of prose style. It’s superb.

On Friday we published an extended extract from his Golden Hill, which we chose as the best-written previous winner of the Ondaatje Prize, part of our project to find the best-written books of the century to date.

—’Bodies are too small to encompass more than a sole inhabitant, except in rare cases of mysticism or possession’: our second pick of the best-written recent releases in nonfiction.

—‘There have been increasing hints this past decade of the wish of the entities to reveal just what exactly they are up to in Dark Matter, and to subtly prank and shock and perhaps even to entertain all of humanity into making the leap behind the scenes into hyperdimensional space’: Parts 10 to 14 of The Demon Inside David Lynch: TV Drama’s Worst Fiasco. The entire series is available here, and a free copy of the fully illustrated .epub is available on request at auraist@substack.com. Thanks for the support Auraist readers have already shown this series, and welcome to the new readers joining us from Twin Peaks sites and groups.

You can also browse our author masterclasses on prose style, picks from the best-written recent releases, from prize shortlists, the best-written books of the century, and extracts from many of these.

Recommend Auraist on Substack, or restack or share this post today, and we’ll send you a complimentary paid subscription (if you share it outside Substack just reply to this email with the relevant link). Or you can join the 16k discerning readers who’ve signed up for free access.

If you’d like us to consider your book in the genre of your choice, please sign up for a paid subscription.

FRANCIS SPUFFORD ON PROSE STYLE

What were the first books you read where you realised you were enjoying the quality of the prose?

I read compulsively as a child, but without being aware of what the writing was doing as writing. In fact, without wanting to be aware of it. My ideal as a reader was total immersion in story, with the prose that achieved that for me behaving as a transparent and indetectable fluid you didn’t have to pay any attention to.

I think the first book where I noticed the written language as such – and noticed that it was decisive to my pleasure – was probably Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, borrowed from a library when I was about fifteen. Here’s the opening paragraph – and I’ll check the quotation before sending it to you, but I can give a first-draft quote from memory.

I’ll give my report as if I told a story, for I was taught as a child on my homeworld that Truth is a matter of the imagination. The soundest fact may fail or prevail in the style of its telling: like that singular organic jewel of our seas, which grows brighter as one woman wears it and, worn by another, dulls and goes to dust. Facts are no more solid, coherent, round and real than pearls are. But both are sensitive.

It probably helped that this was explicitly a narrator telling fifteen-year-old me that it mattered how what followed was going to be delivered. But it mattered more that it was written in a voice. A first-person voice, preternaturally clarified and more formal than a casually speaking voice, as the very first step of the book’s dance with the languages of anthropology and diplomacy; but, still, the voice of an ‘I’ talking to me, and talking very deliberately, and talking unmistakeably in rhythm. My ear was awakened. ‘Report’ rhymed with ‘taught’! ‘Fail’ rhymed with ‘prevail’, and was put next to it as its opposite to make sure I noticed! ‘Singular organic jewel of our seas’, the stately roundabout way of naming what I didn’t understand was a pearl till I was told so in the next sentence, was doing something with its row of long vowels that was almost submarine in itself. Meanwhile, as many words as possible were only one syllable. And oh the comma after the ‘and’, and not before it. I hadn’t known that punctuation, humble old punctuation, could strut and brace a sentence to make fine differences of effect. In this case, rearranging the pauses around ‘worn by another’ so that the emphasis hit ‘dulls’ that little bit harder, and put it into more apparent contrast with ‘brighter’. I was hooked.

I was hooked, and after that, when re-reading other books I loved, I began to see that they too were made of words. Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill was brilliantly layered, a palimpsest of mimicked voices, and also rhythmically deliberate in every sentence. C S Lewis’s Narnia books, which I had inhaled as a child as a stream of pure sensation, were in fact constructed from economical bursts of intense description held within a voice that was sympathetic, unpatronising, and surprisingly logical.

But before we go any further into My Life With Style, I want to insist that books don’t always have to have this patterned, elaborate surface that wants you to be aware of it as you read. That’s one possibility, one choice, but not always the right one. There are a great many situations in writing in which you still want the prose to be unobtrusive in its efficiency; to work like a window you see through, not some embroidered screen which may have pictures sewn on it, but where you’re always going to be conscious they’re made of stitches.

Without being prompted to copy the style, could AI ever write as well as this?

AI’s can’t do either the exquisite conscious-attention-drawing surface or the clear, pure, transparent verbal pane, because both those things proceed from a communicative act. There needs to be a mind there, deciding on a purpose for writing – an end – and then on the means to that end. AI’s offer only a generic remix of the existing state of the art – its conventions, its likeliest moves, understood as a set of probabilities. They cannot make a judgement about what to say or how to say it. They cannot do a new thing. Unfortunately, what I fear they can do is to bugger up the process of laborious apprenticeship by which human beings learn to do a new thing in writing. You can’t get good without first being crap, being mediocre, and being competent at writing. And how many people will be willing to undertake the effort, and let’s be honest the embarrassment, of going through those necessary early stages, when a machine can produce something resembling competence with no effort at all?

Do you read your work out loud, and if so, how important is this to your style?

The acoustics of what I write are very important to me. I test what I’m writing as I go by reading it aloud to myself, and I enjoy the part at the other end of the process where I get to read from my books in public. I want my work to be musically satisfying in a way that enriches what I’m chiefly doing at any one point rather than distracting from it. Beautiful sentences at ugly moments would be… bad. (Unless you define ‘beauty’ in a way that is entirely to do with form following function, and has no prettiness left in it.) But then prose has to be musical, anyway. As Nicola Griffith pointed out elsewhere in this series, it’s rhythm that controls the pace at which the reader experiences the represented world. Sentence length, punctuation, word choice, are all essential, not optional tools. The real choice is between being interestingly musical and boringly musical. Prose doesn’t have the single-minded, audible pulse that you can hear in regular verse form. It has a bigger, looser, more ad hoc repertoire of sounds to choose from. Yet readers, if you let them know their ears are supposed to be set to On for a particular piece of writing, are capable of understanding very fast indeed what you’ve picked out to foreground from that big repertoire of sound possibilities, and how they are supposed to collaborate with you by forming expectations, knowing where the next beat falls, hearing (not necessarily consciously) the run of cadences that means tension rising, or resolution coming. And then, of course, you can play with their expectation, by not providing what they expect, or hitting the equivalent of an off-beat, or by switching in something different but better than what their ears told them was coming.

George Saunders proposed on his substack that it’s in the editing process that literary voice emerges -- the more a writer edits the more they’ll make choices different to other writers, resulting in a voice and style unique to them. Do you agree with this?

I think George Saunders believes that it’s in editing a writer’s voice emerges because of a particular, iterative way of working that he has. I get that strong impression too from reading his A Swim in a Pond in the Rain – a wonderful book – that continually talks of a story as something that gets discovered, by writer as well as reader, one move at a time; one unexpected yet logical move, taking what’s latent in the decisions already taken and moving them on another step, in a direction that declares itself by being found. Revision then clarifies and solidifies. That works for him. But it’s not the only way to write. Not everyone is taking a line for a walk. Not everybody is capable of keeping a whole draft still provisional and mentally sculptable, as you’d need to keep working it and working it in the way George Saunders suggests. (I’m one of the people who can’t go on with a project unless they feel that what’s already done is solid and dependable. I revise and revise as I go, making umpteen drafts by one calculation, or just a single very intensive draft, looked at another way. When I reach the last sentence of a book, I want to have finished.) Also I suspect that, unless you’re George Saunders, it’s an illusion to suppose that revision will necessarily make the voice more and more individual. It might just give you endless opportunities to be dragged toward the attractor of convention.

What stylistic issues were most important to the writing of Golden Hill?

I needed Golden Hill to do some linguistic time travel for the reader, to match the setting of the novel in 1740s New York. I didn’t just want it to be a modern novel with a past setting, I wanted the writing in some respects to wind back to the eighteenth-century dawn of the novel as a form. But only in some respects; not others. I did want the freedom from later genre expectations and, you might say, later literary good manners. You were allowed to throw together pleasures and satisfactions back in the 18th century that later eras would decide were hopelessly incompatible, some being ‘high’ and others distinctly ‘low’. I also wanted the unapologetic one-damn-thing-after-another construction of the picaresque, in which a protagonist would endure a ridiculous density of adventures and experiences without anyone objecting. (People hadn’t yet decided that improbability didn’t go with seriousness.) And, on the sentence level, since the book was so much about disguise, about masking, about performing a self in the world that didn’t necessarily match the real face behind the mask, I needed a style that was thickly, theatrically performative. You had to remember constantly as you read that you were in the presence of artifice.

And yet – and this in fact is where I ran out of homages to eighteenth-century lit – and yet, I also needed the novel to move, to not get clogged and stuck in self-conscious elaboration. So, a decorated rococo surface through which you could also see to people running in the street, flirting, eating, fighting with swords. Real eighteenth-century novels were missing some of the bits of fictional technology that allow for smooth, unobtrusive action, like free indirect style, or fluid changes of viewpoint. I ended up, as a result, with a prose that pretended to be eighteenth-century, but with nineteenth-century wheels and gears turning silently behind the scenes – and the dialogue, it turned out, had to be more modern still, an extra step towards clean and direct, to avoid the awkwardness of costume drama and to keep the reader feeling that the people were real people, no matter how much brocade got draped around them. A kludge, looked at one way; a mishmash of pragmatic, separate decisions that had to get along with each other somehow. But looked at another way, a tailored solution to each of the problems thrown up by the weird thing I wanted to do in the book, carried off with as much energy and conviction as I could manage. And you can get away with a lot, I’m here to tell you, if you just lean whole-heartedly into your weird intentions.

However! This brings me to a probably unwelcome statement of faith, considering where I’m saying it. I’m… not sure I actually believe in the existence of style. Not, at any rate, style considered as an independent variable that it’s meaningful to talk about separately from other aspects of the work. I have never, in anything I’ve done, set out to arrive at a particular style. Instead, I’ve taken a whole lot of decisions – about structure, about viewpoint, about voice, about characters, about setting – and then tried to come up with a good-enough verbal solution for each of them that can co-exist together without fighting. ‘Style’ is then a name for what I end up with. It’s the pattern of gleams on the skin of the thing. But the skin is folded like that, and therefore gleams like that, because of what’s going on underneath.

Francis Spufford is the author of five highly praised works of non-fiction, most frequently described by reviewers as either ‘bizarre’ or ‘brilliant’, and usually as both.

His debut novel Golden Hill won the Costa First Novel Award, the RSL Ondaatje Prize and the Desmond Elliot Prize and was shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award and the British Book Awards Debut Novel of the Year. In 2007 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He teaches writing at Goldsmiths College, University of London and lives near Cambridge.

THE BEST-WRITTEN RECENT RELEASES IN NONFICTION

The books considered this month are listed here. Our next pick is

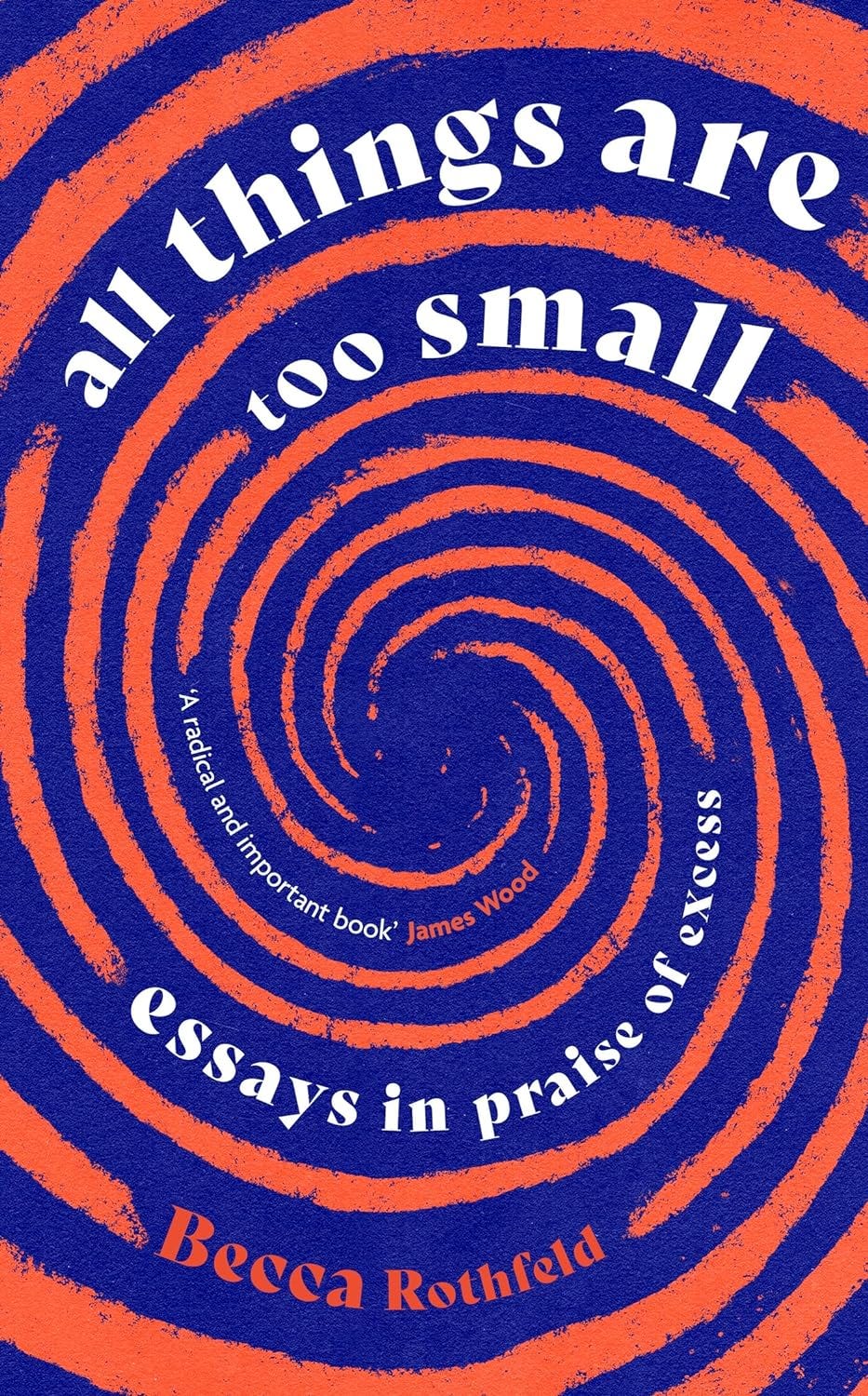

“All things are too small,” begins a poem by the thirteenth-century Dutch mystic Hadewijch of Brabant. She goes on—“to hold me”—but she did not have to. All things are too small, not just to hold me, but to hold anything. Cups are too small, which is why they demand such relentless refilling. Bodies are too small to encompass more than a sole inhabitant, except in rare cases of mysticism or possession (or the more familiar but perhaps no less astounding case of pregnancy). Books can be big—most of the best ones are—yet even the most encyclopedic affairs are too small to encompass the whole of the world’s wild machinery. Moby-Dick can’t reach its arms around a whale—although Melville aims, as James Wood writes, to touch every last word. I once saw a man in a restaurant finish his pasta, order the same dish again, eat it, then order and finish it a third time. His was the sanest response to his predicament, but he wouldn’t have had to grasp at such exorbitance if any plate available were big enough.

Plates, cups, books, bodies, and all the rest are too small, not contingently, but constitutionally. There is no way around the sense, lodged hard in the throat, that the greatest human longings exceed any possible fulfillment. To want something with sufficient fervor is to want it beyond the possibility of ever getting enough of it. Is it this longing, phenomenologically keen enough to strike some of us as fact, that has led religious thinkers to posit the existence of eternity, the logic being that we seem to need it? Desire is as good a guide to truth as anything else, but until eternity arrives, we will have to find somewhere to fit our appetites. One way to proceed is to shrink them—first by making concessions to smallness, then by framing contraction as wisdom or virtue. This is the minimalist tack, and these days, it is on the rise. At every turn, we are inundated with exhortations to smallness: short sentences stitched into short books, professional declutterers who tell us to trash our possessions, meditation “practices” that promise to clear the mind of thought and other detritus, and nostalgic campaigns for sexual restraint. These adventures in parsimony each make their own particular mistakes, but they also share a central failing. There is nothing admirable in laboring to love a world as unlike heaven as possible. All things are too small, but some things are less small than others. Even if paucity is inevitable, we can still fight emptiness with fullness. Better to order the third plate of pasta. Better to graze each word once.

The Demon Inside David Lynch states that the celebrated director was possessed by a ten-dimensional entity that went on to make Twin Peaks: The Return. Obviously this is fiction, satire.

The Erasure

[Trinna/Andy]

…

‘… Now what if we were to tell you that in the finale of The Return we find out not a single one of the main Twin Peaks events which we have described to you so far really happened?’

‘Because that’s what we’re now telling you. In the finale’s notorious retcon, Dale Cooper travels back to 1989 and prevents Laura being killed by Leland/BOB, which means every event that follows from that murder’s been erased.’

‘This time travelling occurs with the help of a jumbo teapot.’

‘A jumbo teapot that releases puffs of steam containing the voice of a poorly imitated David Bowie.’

‘This is not the rock bottom, by the way. Oh no, señora. Nowhere near! The rock bottom is worse than this by many multiples.’

‘This erasure has provoked anger and ridicule but not the full bodylock that afflicts so many once they see the rock bottom. The retcon may hint at the nature of that rock bottom, may provide an important clue since its deletion of almost the entire preceding Twin Peaks narrative is part of Season 3’s war on nostalgia and retro^^. But that bottom itself is on a completely different plane from this. This? This is just world-class garbage, señora. So we can get over this element of the series, no matter how toe-curling it is.’

‘No, we can. We can. We can move on from it, in new boots if necessary. We can recover from it.’

‘In a sense.’

‘In a sense.’

The Erasure of the Erasure

‘Now what if we were to tell you that we then find out in the finale that this journey back in time did not actually happen either? What then, señora?’

‘Please bear with us here. Please. We’re not having you on. Fire Walk with Me, the original Twin Peaks, the seventeen previous episodes of The Return, and Cooper’s erasure of nearly all of this when he whooshes back in time and stops Laura being murdered—later on in the series finale we discover that every bit of it was the dream of a guy in a motel who we’ve never met before called Richard.’

‘When you get home and watch the series as you promised and experience its many lows, therefore, you should always remember that they were not only wiped out by the time travelling of Dale Cooper but that they also never even happened to begin with because they were just the fragments of some man named Richard’s dreaming.’

‘And because it erases even more of the Twin Peaks narrative and so contributes further to the war on nostalgia and retro, this erasure of the erasure anticipates the rock bottom too.’^^

The Erasure of the Erasure of the Erasure

‘The most impressive essay about the series, Tim Kreider’s justly celebrated ‘But Who Is the Dreamer?’, argues that the erasure of most of Twin Peaks by the retcon and this then turning out to be Richard’s dream are themselves just dreamt or hallucinated by yet another unknown man, and thus confronts us with the not just world-class but world-historic garbage of the erasure of the erasure of the erasure. If you want a bleakly illuminating time—’

‘Buy some muscle relaxant and rub some on your bottom. Not on your buttocks, no. On your bottom, sí?’

‘Read Kreider’s essay—’

‘Rub it on to stop your bottom clamping dangerously hard and long and then read Señor Kreider’s essay.’

‘At quarterly.politicsslashletters.org/dreamer-twin-peaks-return.’

‘And then let what he is saying sink into your mind.’

‘Unlike the series’ absolute rock bottom, which causes immediate wails and clutched skulls, this one’s a grower.’

‘But when it does sink in, we promise your skull will be getting clutched!’

Back to the Future

Are you beginning to see why we couldn’t believe how rank this series is, and the likes of Vulture rating it above Mad Men?

And I’ve only given a summary of the finale, a brief recap. None of this can give a proper sense yet of the ugliness and chaos and cack-handedness with which this trainwreck unfolds, or un-unfolds, or un-un-unfolds, or un-un-un-unfolds, or the tediousness, incoherence, wooden performances, and just the general air of contempt that are the most notorious things about the series.

The retcon, it’s true, was so ridiculed when it first aired that cultists scrambled about to find some angle from which to deny it really was a retcon, to insist Laura had definitely died even though every viewer saw her lakeside corpse fade and disappear. Then Mark Frost’s book The Final Dossier confirmed that she never died (‘Laura Palmer did not die’, italicised in the book), and therefore that the entire Twin Peaks narrative was built on a now-void event. End of story, literally, at which point the Césars switched to yet more doublethink. Laura never died after all, eh? Cool. Lynch is a geeenius.

Picture The Sopranos’ finale and FBI agent Dwight Harris travelling back to the late 1960s to persuade Tony not to join the Mafia. This is followed by a shot of Big Pussy’s corpse as it jumps backwards out of the sea into what is now Silvio’s boat. We are to understand that every other event in the whole story didn’t actually happen either and are given a sequence showing the Soprano family living a Mafia-free life with Tony as a bland Kevin Finnerty type.

Maybe you feel that comparing The Return to one of the US’s most accomplished TV dramas is unfair. If so, all I can say in response is that the Césars compare them too and conclude that The Sopranos is by far the lesser work. Same with The Wire, Vertigo, Hiroshima Mon Amour. Many of them claim the show is better than anything else ever made. Cahiers du cinéma called it the best film of the decade, while Manhattan’s MoMA screened the full series.

Wait a minute, you’re possibly thinking, Cahiers du cinéma and MoMA? That’s impressive. Why should you trust over Cahiers and MoMA some nobody security guard, an alkie who struggles with physical and mental grappling and who eventually involved the Policía Nacional in his thoughts on TV drama, and who got a little too keen on research chemicals and a sexdoll?

And all I can say is please don’t take my word for any of this. Please go and watch YouTube clips of the fiasco yourself, as many as you can get through. But be warned. Cahiers and MoMA are unlikely to change your view of The Return, but The Return may well change your view of Cahiers and MoMA. As with the second-biggest diddy this world has seen, every single thing it touches is damaged by association.

Alternate plotline for Hiroshima Mon Amour: Elle and Lui travel back in time to assassinate Einstein in childhood so splitting the atom and making A-bombs can be delayed long enough to screw up the film we’re watching. St. Elsewhere: the whole series turns out to be the invention of an autistic child; Dallas: an entire season turns out to be Pam Ewing’s dream. These last two examples really happened, of course, and are cited to justify Cooper’s journey back in time and everything being Richard’s dream because, you see, the Césars respond, The Return is a pastiche of soap operas like St. Elsewhere and Dallas.

Here we’ve arrived at a core reason why the series is so wretched, which is how undisciplined and lazy it is, and therefore how sloppy and irresponsible. It takes discipline and care to maintain a balance, and when necessary a strict division, between pastiche, cheesiness, and zaniness on the one hand, and on the other plotlines involving a girl forcibly lapping up her father’s semen, life-destroying adult-rape, the torment of a disabled character, and many more storylines and events just as weighty. The manner in which the original Twin Peaks maintained equivalent balances and divisions was among its most impressive achievements but in the Return the seriousness, care and discipline to preserve these are all missing.

Dozens of mainstream publications have praised the trainwreck and its showrunner, and a few filmmakers have done the same, but we can be sure that no mainstream publication will praise a retcon resembling the trainwreck’s, should such a stunt ever appear onscreen, and no human filmmaker will include such a stunt in their own work. None will ever turn to their co-creators or producers and suggest they delete their work’s central event and everything that follows from it over many years, or suggest anything that rotten. You know they won’t and so do they.

They’re fine with Season 3’s retcon not because they’re genuinely fine with it but because the Master’s name is stamped on it, just as Trump cultists like Trinna are only okay with the theft of nuclear secrets because it was the great man who stole them. Picture Trinna’s head erupting and sending her security cap flying if George Soros refused to hand over stolen nuclear documents. Now picture the equivalent arc of César’s cap and severed manbun if Richard Curtis had been brought in as showrunner for The Return and he’d sent Cooper back in time to prevent Laura’s murder. In both cases the cap’s trajectory gives an exact measure of the indoctrination.

And of course as those same mainstream publications were re-anointing the quiffed showrunner with the 4channish take on sexual abuse as a genius, often on the same day they were cheering on #MeToo and castigating showbiz abusers they’d fawned over just days or weeks before, and castigating another boomer with flamboyant hair as a rapey buffoon.

The retcon is also mince because Green Glove versus BOB and everything being Richard’s dream and even this itself maybe being a dream, plus so many more artistic choices throughout the series are mince as well. When you get to the finale of a drama that’s this mince this often, you aren’t inclined to give the artist responsible any benefit of the doubt. This is one of the ways in which The Return is the opposite of a masterpiece.

How masterpieces work on me is similar to falling in love, in that to the extent that I understand the process at all it doesn’t seem additive but multiplicative. You’re captivated by A then B then C then D and so on, and each is then multiplied by some combination of the others in ways too complex and mysterious to understand till you cross a Line and you find you’ve suspended your disbelief and you’re in love, with e.g. the drug-sharing Laura Palmer lookalike, or sometimes with the masterpiece too if it’s special enough, as in the case of Fire Walk with Me. From that point onwards, because they’ve proved worthy of this so often you do give the benefit of the doubt to the people or things you love.

And the opposite happens with The Return, which is why watching it can feel so like the death of love, because its every display of contempt is multiplied by all the rest and you find that you now despise what you once loved.

The Prank

[Ella]

There have been increasing hints this past decade of the wish of the entities to reveal just what exactly they are up to in Dark Matter, and to subtly prank and shock and perhaps even to entertain all of humanity into making the leap behind the scenes into hyperdimensional space.

Then with the events recounted in this narrative they stopped messing around and made it very clear that other planes connect with this dimension of ours, levels of being where live puppeteers with fancy ideas and quite an odd sense of humour. They made it clear that the winks and the nudges of their elbows and the long wait for our evolutionary leap were over, that the long prologue was now over. They made it clear they existed and they were going to show us what was what. So to try to bitchslap us all out of the sty we live in they put together this David Lynch mystery with the Demonic Twin in the role of Big Bad or heel.

Without these entities you would not be reading this or have done many other things in your life. Every act of yours is what we could call a building-block in the spacetime architecture of the entities which props up what they call their Argument leading to what they call their Absolute Reconciled Vision, also known as the Promised End, which really just means everything being perfect everywhere and for always.

They are not what we would call nice, however, because without the actions of the Twin and other demons, they believe, the Argument will lead to no such perfection everywhere. These actions are the blinks necessary for sight and without which we’d go plecto—try to stare with eyes open forever and see how sane you feel. These actions are the rock bottom, plague, collapse of ecologies, humiliation in the wrestling ring, broken heart, artistic cataclismo, or maniac in control of nuclear weapons which is necessary to make us so desperate for change, any kind of change, that we shall open up to what is needed to risk the next jump in evolution, individually or all together.

You could think of the entities as prankster Brian Enos which fade into different parts of the Ultraverse to twiddle away at trillions of knobs from the quantum level all the way up to the galactic level, every single twiddle to help bring about that Promised End, is what they believe. This will hopefully all make more sense to you once poor Andy has his shattered freaking out and as a result merges with an entity.

As he has said, ten entities have been involved in what happened to Mr Lynch, nine that mainly fiddled with knobs in the background, and the Twin which played the leading role. And as everyone now knows, that Twin was of the sub-type the other entities call demon (or in the language of wrestling it played the heel), meaning there are lots more entities of that sub-type and so lots more entities generally. Note this number ten, please. The fact that the entities operate in groups of ten was eventually to prove crucial to finding out what had happened to dear old David Lynch.

Here I am back again. Sean, I think "voice" comes first and editing infuses that voice with concision. Editing is the secondary task in that way. The invention included the "voice" of the writer and I'm hoping that you can see that in my work. What do you think on editing as the secondary task--absolutely necessary, but secondary--even though sometime seemingly never ending.

I actually have much to say--but need some time to do so, Will be back to you, Sean.